Sequencing thousands of whole genomes yields new autism genes

An analysis of whole genomes from more than 5,000 people has unearthed 18 new candidate genes for autism.

An analysis of whole-genome sequences from more than 5,000 people has unearthed 18 new candidate genes for autism. The study, the largest yet of its kind, was published today in Nature Neuroscience1.

The new work identified 61 genes associated with autism, 43 of which turned up in previous studies. An independent study published last month looked at several autism genes and made a strong case for three of the new genes2.

Most of the new candidates play roles in cellular processes already implicated in autism and intellectual disability. They also point to possible new treatments.

“Eighty percent of them involve common biological pathways that have potential targets for future medicines,” says study investigator Ryan Yuen, research associate at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada.

The study is the largest analysis of whole genomes from people with autism and their family members to date. Participants are enrolled in MSSNG, an effort funded by Google and the nonprofit group Autism Speaks to analyze sequences from 10,000 people.

Other studies typically focus on the coding regions of the genome, called the exomes. Most of the mutations identified in the new work land in genes, but some affect noncoding regions of the genome.

Understanding the role of these noncoding mutations is a “challenging task,” says Ivan Iossifov, associate professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, who was not involved in the study. “The more data that’s available, the better,” he says. “This paper provides a very useful resource for the community to further study.”

New genes:

The researchers analyzed whole-genome sequences from 5,193 individuals, about half of whom have autism. About 3,100 of the participants are from simplex families, with a single child affected by autism but unaffected parents and siblings; the remaining are from multiplex families, which have two or more affected siblings. Genetic risk factors tend to be inherited in multiplex families and arise spontaneously in simplex families.

People with autism carry an average of 74 spontaneous, or de novo, mutations, the researchers found. They also have an average of about 13 large DNA duplications or deletions, called copy number variations (CNVs).

Not all of these mutations may be harmful, however, so the researchers zeroed in on 230 harmful de novo mutations that abolish the function of the corresponding protein. They combined their data with findings from previous studies to increase statistical power.

The combined analysis revealed 54 genes tied to autism.

When the researchers also considered inherited mutations on the X chromosome in boys and men with autism, they identified seven additional autism-linked genes, bringing the total to 61 genes. Roughly 4 percent of participants have harmful mutations in one of these genes.

One of the 15 new genes, MED13, is related to the intellectual disability gene MED13L. MED13L emerged as an autism candidate in the study published last month. The new study identified harmful MED13 mutations in three families.

Harmful mutations in another new candidate, PHF3, appeared in four families. PHF3 is related to PHF2, which has been linked to autism in previous studies. PHF3 encodes a protein that regulates the structure of chromatin — the coiled complex of DNA and protein.

Common pathways:

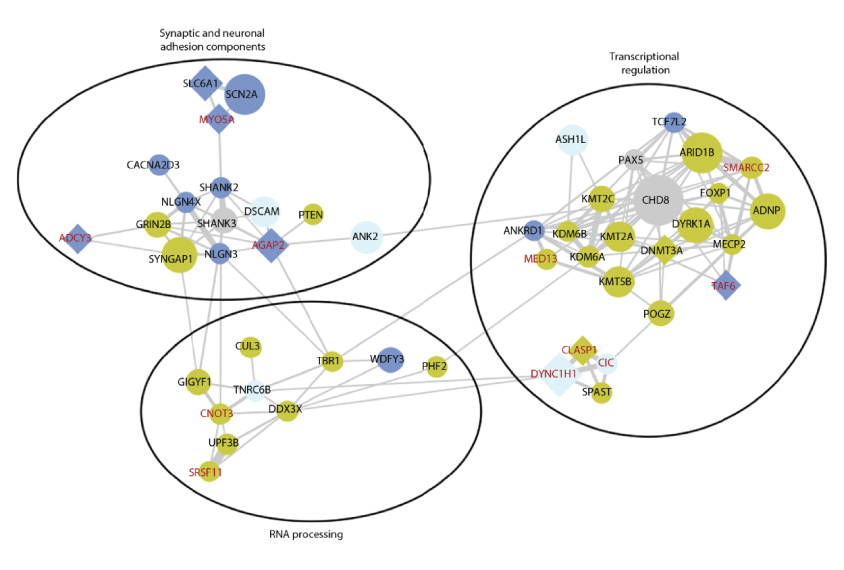

Of the 61 genes unearthed in the new study, 49 play a role in chromatin remodeling, RNA processing or building connections between neurons. These findings are in line with those of previous studies. They highlight the fact that these genes are functionally related and tend to work together.

“If you identified genes that were completely random and not related to each other, that would be suspicious,” says Iossifov.

The study identified CNVs across coding and noncoding parts of the genome. About 7.2 percent of participants with autism carry one or more harmful CNVs, the researchers found.

They identified three new autism-linked CNVs that were too small to be picked up by standard sequencing techniques. They also uncovered five CNVs linked to autism that land in noncoding regions of the genome.

Participants with autism who carry a harmful CNV have lower intelligence quotients than those who carry a harmful mutation in a candidate gene. But they score higher on a test of adaptive functioning, which measures daily-living skills.

This finding suggests that mutations in genes give rise to autism’s behavioral features, whereas CNVs underlie problems with cognition.

Other scientists can access the 5,200 whole-genome sequences online. The researchers plan to add more sequences over the next month, bringing the total to 7,000.

References:

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt