Knocking down 19 genes linked to autism, one at a time, shakes up a network of other genes, many of which regulate the early proliferation and differentiation of brain cells, according to a new preprint. Some people with autism carry rare variants of certain genes in the network, previous research has found. Others have been implicated in genome-wide association studies of autism, which reveal common genetic variants that may work in combination to increase autism likelihood.

“We’re finding this really interesting signal of autism-associated genes that are changing when we perturb just a single autism-associated gene,” says study investigator Rebecca Andersen, a postdoctoral researcher in Christopher Walsh’s lab at Boston Children’s Hospital. “That could explain how [disruptions to] these different autism-associated genes could all lead to similar neurodevelopmental phenotypes and, eventually, a diagnosis of autism.”

Knocking down any of eight stretches of noncoding RNA that neighbor a subset of the 19 genes also alters the network’s expression, the researchers found. Autism-linked genes are particularly prominent in the network after knocking down six of the long noncoding RNAs, Andersen says.

The findings, shared on bioRxiv in January, help to illuminate how a large and heterogeneous group of genes could be involved in autism, according to Nenad Sestan, Harvey and Kate Cushing Professor of Neuroscience at Yale School of Medicine, who was not involved in the work.

“This group and others have been trying to move the needle by looking for a theme in these big datasets,” Sestan says. “And I think that this study has moved the needle.”

E

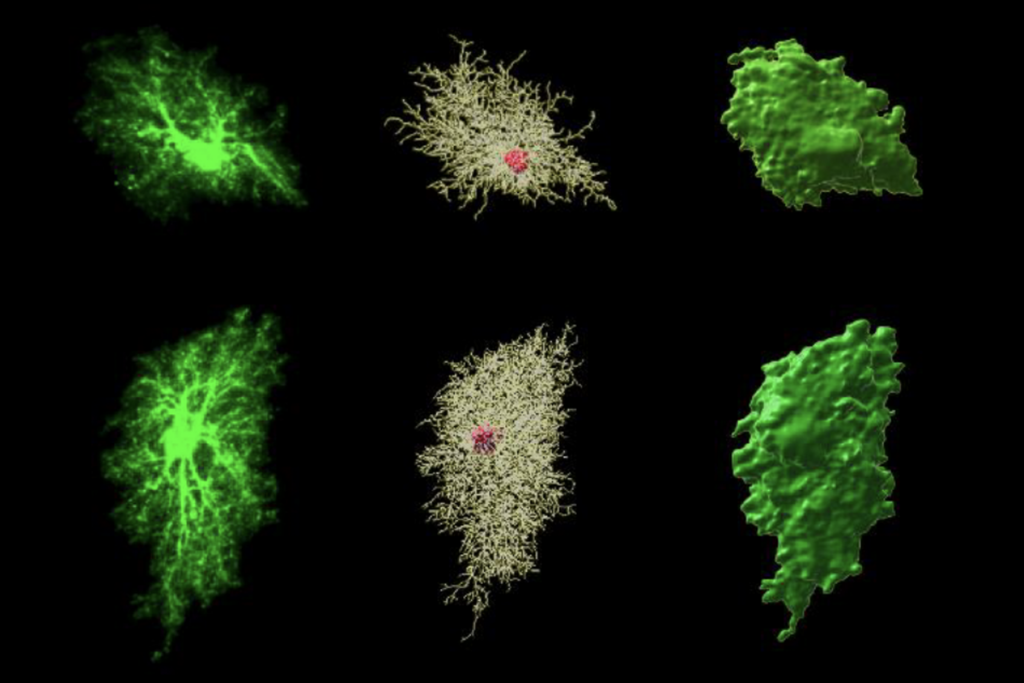

ach of the knockdowns, carried out one at a time using CRISPR in human neural progenitor cells, changed the expression of up to 2,463 other genes, Andersen says. And there was a “striking degree of convergence” between the differentially expressed genes across all experiments, she adds.The investigators gauged expression levels by sequencing RNA from the neural progenitor cells in bulk. That approach addresses the limitations of past work done using brain organoids and postmortem brain tissue, Andersen says, which were limited by the challenges of comparing multiple cell types and relying on single-cell RNA sequencing.

“Having a very homogeneous model system was a huge advantage,” she says. “We think that this convergence is likely shared across different cell types. However, the specifics of how these gene regulatory networks are set up likely does have a cell-type-specific component to it.”

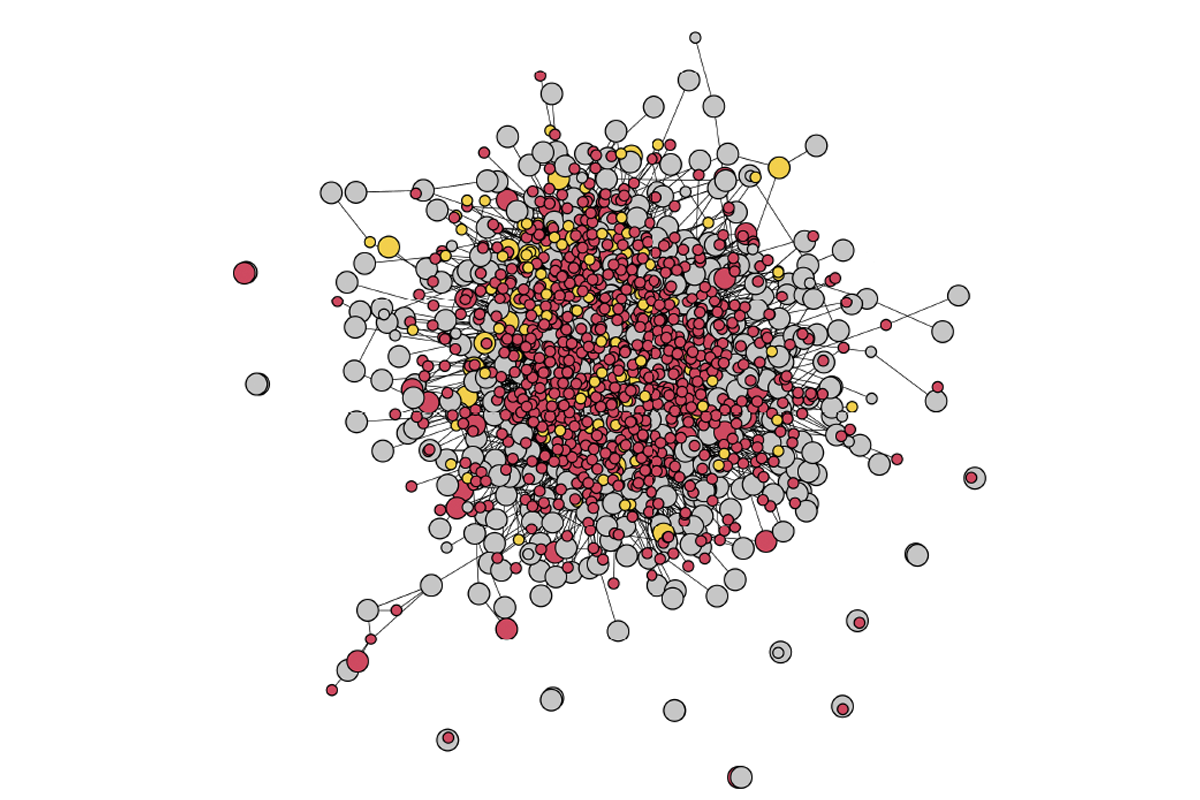

In total, the regulatory gene network includes 9,294 protein-coding genes, as well as 161 long noncoding RNAs. The researchers then analyzed 1,874 protein-coding genes and five long noncoding RNAs that they had previously identified as autism-linked and had listed in a database called Consensus-ASD.

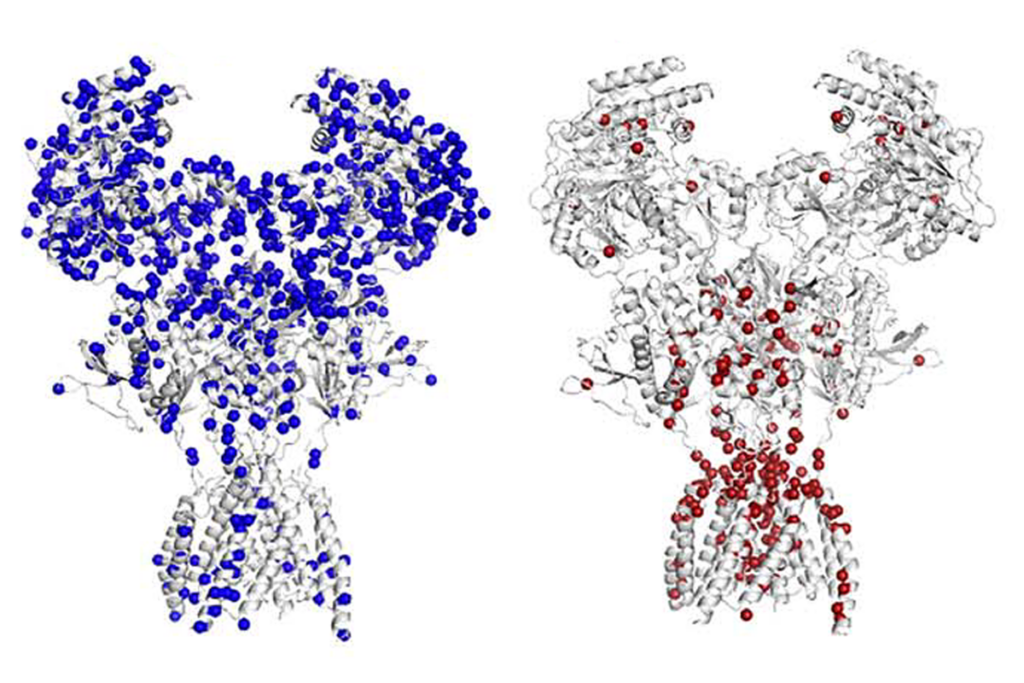

A total of 78 genes regulate the expression of multiple Consensus-ASD genes, they found. Chief among these central regulators is CHD8, a gene strongly linked to autism that is involved in chromatin remodeling and is known to regulate dozens of other autism-associated genes.

Another central regulator, REST, has target genes that showed altered expression in response to all but one of the knockdowns tested. REST, which is involved in neurogenesis, was not previously implicated in autism.

But it’s unclear whether REST disruptions alter the expression of autism-associated genes more than other neuronal genes, says Lilia Iakoucheva, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the study. The researchers, she says, “need to validate the network by taking the most important targets that they implicate and doing experiments where they modulate the activity of those factors and see whether autism genes are more involved than other neuronal genes.”

T

he network also includes ZFX, a transcription factor on the X chromosome that regulates sex differential gene expression. ZFX has been previously linked to autism and may help to explain the condition’s preponderance in boys.For four of the eight long noncoding RNAs, the RNA’s knockdown decreased the expression of its neighboring gene, the researchers also found. These changes are frustrating from a therapeutic perspective, Iakoucheva says, because some autism-associated variants essentially wipe out the expression of the affected gene copy. If you could increase the expression of the healthy gene copy by manipulating its neighboring long noncoding RNA, you might be able to restore some of the lost gene function.

Andersen and her colleagues plan to publish Consensus-ASD and the regulatory gene network with their study so others can analyze the cascading effects of variants associated with autism as well as common variants. “It might require multiple hits of different common variants to lead to this kind of signature that we’re seeing, so this gives us a framework to see how much of an impact any given perturbation has,” Andersen says.

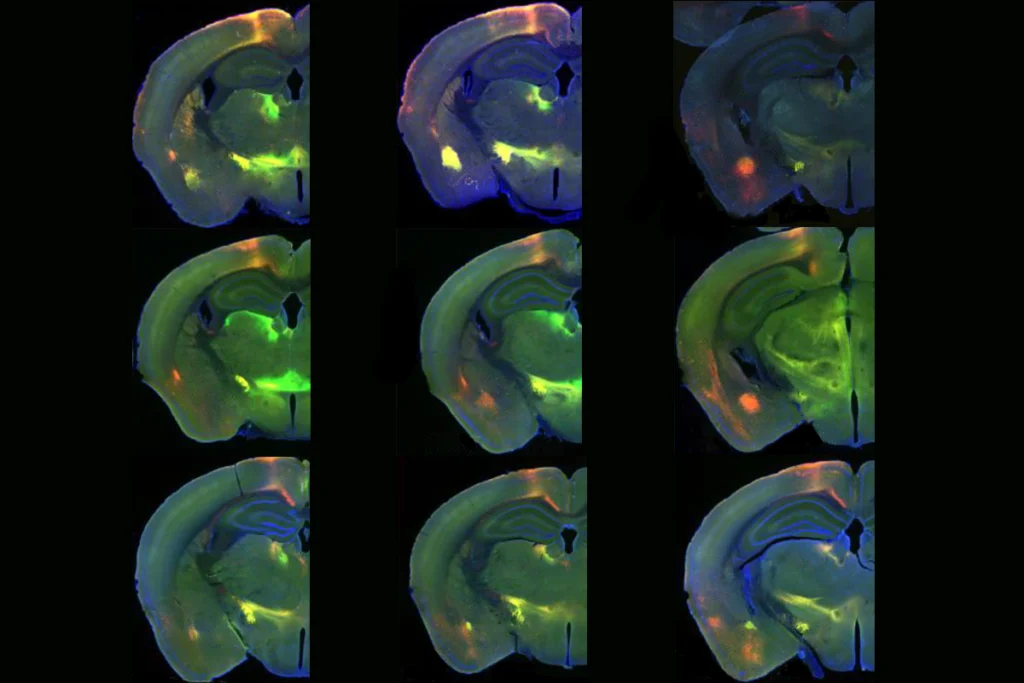

The researchers are testing the effects of silencing autism-associated genes and neighboring long noncoding RNAs on the regulatory gene network in organoids with different brain cell types and plan to integrate those findings into the study.