A new analysis links individual mutations in a gene called PTEN to a person’s odds of having autism, cancer or other conditions1. The findings may help clinicians and researchers predict the effects of various mutations in the gene.

PTEN controls cell growth and regulates the strength of connections between neurons. Mutations in the gene are associated with a variety of conditions, including autism, macrocephaly (enlarged head size), benign tumors and several types of cancer. It is still unclear how different mutations cause such varied effects.

Scientists cannot easily predict the consequences of a PTEN mutation based on its type — whether it involves a single amino acid change or a larger interruption to the gene, for example — or its impact on the protein the gene encodes. Researchers have developed methods to examine the molecular effects of PTEN mutations within cells in a dish, but these approaches do not link mutations to specific conditions in people.

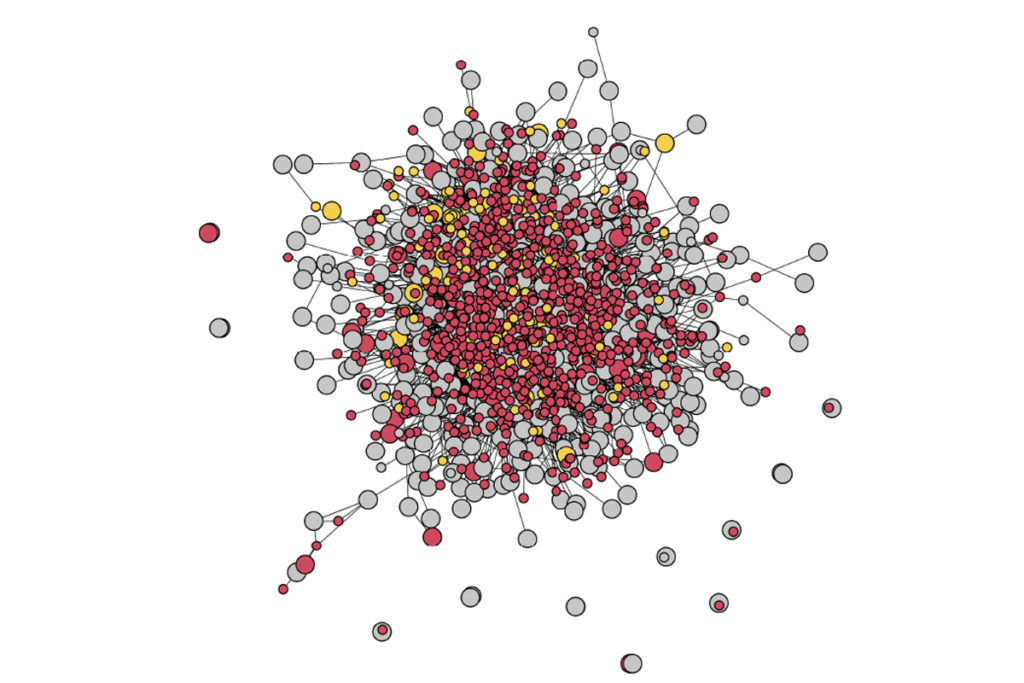

In the new analysis, the researchers probed the effects of 7,657 PTEN mutations, representing all possible changes to each amino acid in the gene’s sequence. They built on the findings from a previous study in which they used yeast cells to calculate a ‘fitness score’ for 7,244 PTEN mutations2. They combined this dataset with another in which researchers had given an ‘abundance score’ to 4,112 PTEN mutations based on how those mutations affect protein levels in human cells in a dish3.

The team used machine learning on the combined dataset to calculate abundance and fitness scores for mutations that lacked them. They then compared these scores with data they gathered from 421 people with PTEN mutations — 165 controls and 256 people with a PTEN-related condition, such as autism, developmental delay, intellectual disability, macrocephaly, or benign or malignant tumors.

Combined catalog:

People with the largest head size tend to have mutations with the lowest fitness and abundance scores, the researchers reported in June in the American Journal of Human Genetics. Similarly, low scores track with having PTEN-related conditions that are severe or appear at a young age.

By comparing mutations in individuals with PTEN-linked traits and those in controls, the researchers also found that fitness scores can predict whether a mutation is likely to lead to a PTEN-related condition.

Together, these findings suggest that abundance and fitness scores may help predict the consequences of PTEN mutations, the researchers say.

The team also split single amino acid changes into three classes based on the severity of their effects on protein function and abundance.

The most severe mutations are linked to a higher likelihood of cancer diagnosis by age 35 compared with the least severe mutations, the researchers found. Greater severity also tracks with an increased likelihood of tumor-like growths.

However, the severity of the variants’ effects is not tied to a person’s likelihood of having autism or developmental delay. This suggests that even a small decrease in PTEN activity may be enough to significantly increase the odds of having a neurodevelopmental condition, the researchers say.

The analysis may help tease apart PTEN mutations’ different effects, the researchers say. It may also help researchers identify the mutations most likely to play a role in autism and prioritize them for further research.