Scientists plan to release thousands of whole autism genomes

Researchers have sequenced the whole genomes of 1,000 people with autism and their parents, they announced yesterday at the American Society of Human Genetics Annual Meeting in San Diego. These sequences, and another 1,000 that are on the way, will eventually be freely available online.

Researchers have sequenced the whole genomes of 1,000 people with autism and their parents, they announced yesterday at the American Society of Human Genetics Annual Meeting in San Diego. These sequences, and another 1,000 that are on the way, will eventually be freely available online.

“We really want a turnkey solution where if you have an idea, you can turn the key, test the hypothesis, get the answer as soon as you can and go out and find out more,” says lead investigator Stephen Scherer, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto. “We want to level the playing field worldwide and get as many eyes, minds and curiosities to the data [as possible].”

The data are part of the Autism 10,000 Genomes Project, or Aut10K, a massive effort to sequence the DNA of 10,000 people with autism and their families. The autism advocacy and science organization Autism Speaks launched the project in 2011. But at the time, there was only enough funding to sequence 100 genomes. Earlier this year, the team announced that philanthropic contributions, money from the Canadian government and a partnership with Google had brought them closer to the final goal.

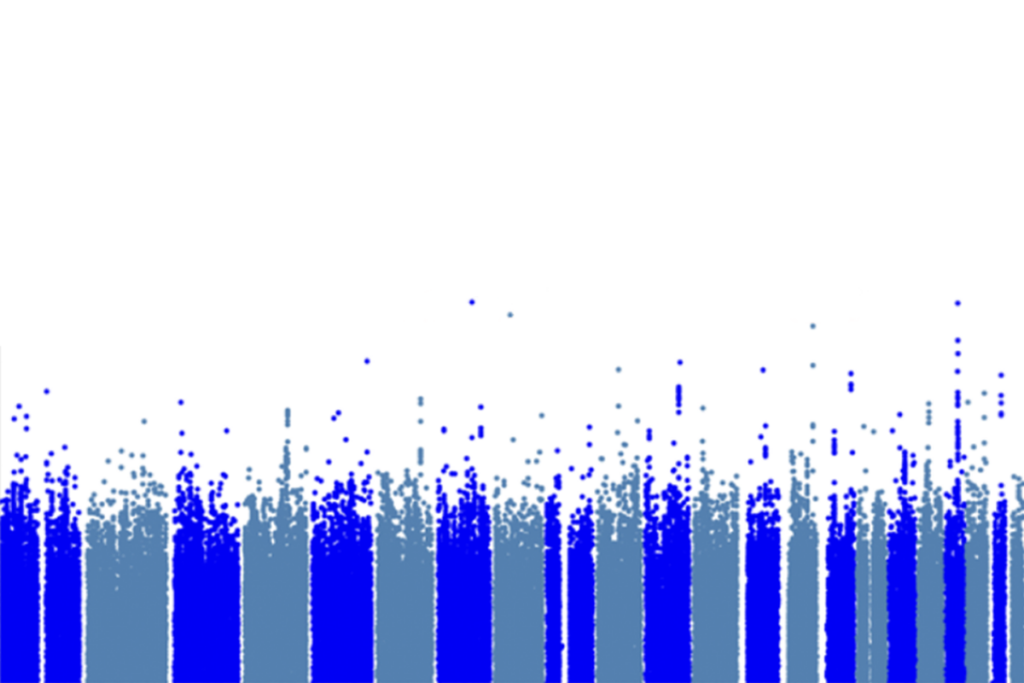

The venture aims to identify every type of genetic variant associated with autism, including many that would be missed by focusing only on protein-coding regions of the genome, or exomes. Much of autism research has focused on exomes because whole-genome sequencing, while becoming more affordable, still costs thousands of dollars per sequence.

Autism is too complex to solve by looking at only one type of variation, says Scherer. Most studies miss small structural variations, inherited mutations, variants in the X chromosome or regulatory regions between genes. “We need to capture all these different types of variants to really understand the architecture of autism,” Scherer says.

Last year, his team analyzed the whole genomes of 32 children with autism and their families. They have since analyzed 340 genomes. On average, they found about 73 genetic variants present only in a child with autism and not in his or her parents. Broken down by mutation type, each autism genome has an average of 59 variants, 13 insertions or deletions of single nucleotides and 1 duplication or deletion of a stretch of DNA. About 5 percent of the autism group has rare, harmful mutations outside the exome.

For example, two children with autism both have a 1.7-kilobase deletion in the gene SCN2A, which has been linked to the disorder. Because the deletion lies in regions of the gene that are spliced out of its corresponding protein, exome studies would have missed it.

For more reports from the 2014 American Society of Human Genetics Annual Meeting, please click here.

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects