Romanian orphans reveal clues to origins of autism

Understanding autism features in children who were deprived of social contact as infants could offer clues to the condition.

There are many risk factors for autism, some genetic and others environmental. But few are more intriguing — and disturbing — than psychosocial deprivation in infancy.

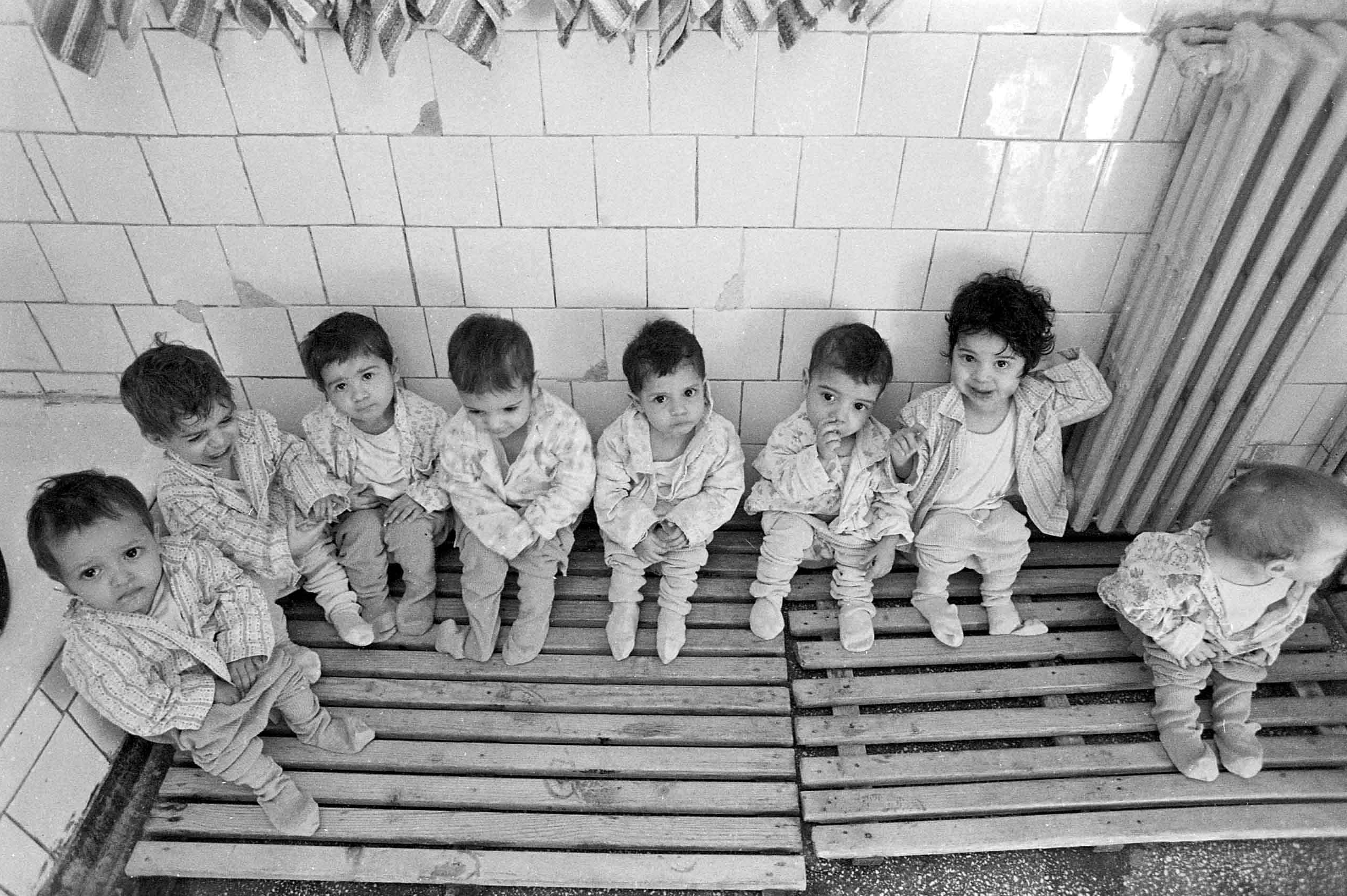

Psychosocial deprivation is essentially a lack of caregiver stimulation and investment. It is particularly common among children reared in institutions. Researchers, myself included, have been studying the effects of psychosocial deprivation in Romanian children who were institutionalized as infants. These orphans lived in large white rooms crowded with cribs. They were fed and changed but otherwise ignored.

After the Ceausescu regime ended in December 1989, journalists from the United States and Europe flooded into the country and began to report on the plight of the more than 170,000 children living in state-run institutions.

Many of these orphans were adopted as young children and went on to better homes. But up to 10 percent of these adoptees still have persistent social difficulties and repetitive behaviors — a set of features sometimes referred to as ‘quasi-autism1.’

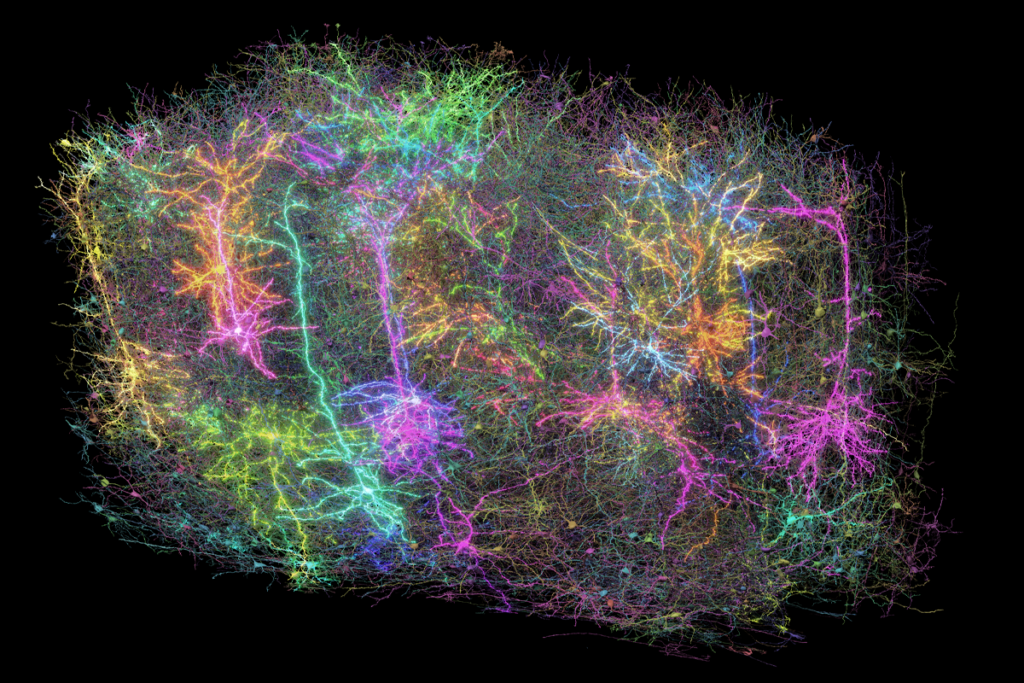

Autism features in these children are most likely rooted in their early lack of social experience. Experience serves as the set of instructions that guide the formation of circuits in the developing brain. When deprived of experience, the brain is left to wire itself, and the process can go awry.

The path to autism in Romanian orphans is likely to be different from that of other children with the condition. Whether the orphans who are diagnosed with autism even have the same condition as others with the diagnosis is debatable.

Yet understanding what gives rise to autism features in children who were socially deprived as infants could offer clues to these features more broadly, and hint at interventions to ease them.

Seeking stimulation:

Two studies have addressed the link between early psychosocial deprivation and autism. The English Romanian Adoptees study, which began in the early 1990s, is tracking the development of 165 Romanian orphans who were adopted into homes in the United Kingdom before age 2. About 10 percent of the children adopted after 6 months of age were diagnosed with autism sometime in childhood2.

I am co-leader of a second study, the Bucharest Early Intervention Project, in which a team of researchers has followed 136 Romanian orphans from as early as infancy into adolescence. At the start of the study, the children ranged from 6 to 30 months of age, when we assigned half of them to a high-quality foster care program; the other half remained in institutional care. About 5 percent of the children meet the criteria for autism regardless of whether they entered foster care3.

Children in both studies were deprived of a range of experiences and stimuli as infants. They had little to look at or listen to other than the babies in cribs beside them. No one talked to them, played with them or responded to their cries.

Infants who lack external stimulation often resort to self-stimulation. A common form of self-stimulation is repetitive behavior, such as hand flapping or rocking. We found that more than 60 percent of children in our study show these behaviors, even though most fall short of an autism diagnosis.

Interestingly, placement into high-quality foster care after infancy but before the age of 2 is associated with a dramatic decrease in the prevalence of repetitive behaviors by age 54. The foster care provided the children with the social interaction and sensory stimulation that they had lacked earlier.

This improvement suggests that neural circuits that underlie repetitive behaviors can be rewired within a certain window of development. So early intervention may be particularly useful at ameliorating this feature of autism.

Social circuits:

Social difficulties, by contrast, often persist into adolescence, long after the children have entered foster care or adoptive families. For example, many of the orphans show indiscriminate social behavior, such as hugging or jumping into the arms of strangers. They also have difficulty relating to their peers5.

Children who left the orphanages before age 2 tend to show subtler social difficulties than those who left later or who remained institutionalized. But the fact that some difficulties remain suggests that there is a critical period for aspects of social and emotional development. If children fail to receive the stimulation required to facilitate healthy development, they may not recover.

Many of the children in our study are now teenagers, and have lasting social difficulties regardless of whether they entered foster care before 2 years of age. They are awkward when initiating interactions with peers or responding to invitations to play, and their teachers rate them as less socially skillful than their peers.

The persistence of these problems is additional support for the idea that the neural circuits underlying social behaviors are forged during the first two years of life, and are relatively inflexible after that age.

Most researchers who have met the Romanian orphans agree their condition appears to be different from classic autism. So it is unclear whether the mechanisms underlying the features of these orphans are the same as those that underlie autism.

Still, there are lessons scientists can learn from these children — notably, that psychosocial deprivation can, in some children, lead them down a path that looks similar to what we think of as autism. In particular, we don’t know why 90 percent or more of the orphans do not develop autism. Perhaps there are genetic risk factors — or resilience factors — at play.

Identifying the environmental contributions — particularly, those involving caregiving — to the features of these children may reveal treatment opportunities for all forms of autism.

Charles Nelson is professor of pediatrics and neuroscience at Harvard Medical School and director of research at Boston Children’s Hospital’s Developmental Medicine Center.

References:

- Rutter M. et al J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 1200-1207 (2007) PubMed

- Sonuga-Barke E.J.S. et al Lancet 389, 1539-1548 (2017) PubMed

- Levin A.R. et al J. Am. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 54, 108-115 (2015) PubMed

- Bos K.J. et al Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 164, 406-411 (2010) PubMed

- Zeanah C.H. et al. Child Dev. 76, 1015-1028 (2005) PubMed

Syndication

This article was republished in The Washington Post.

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

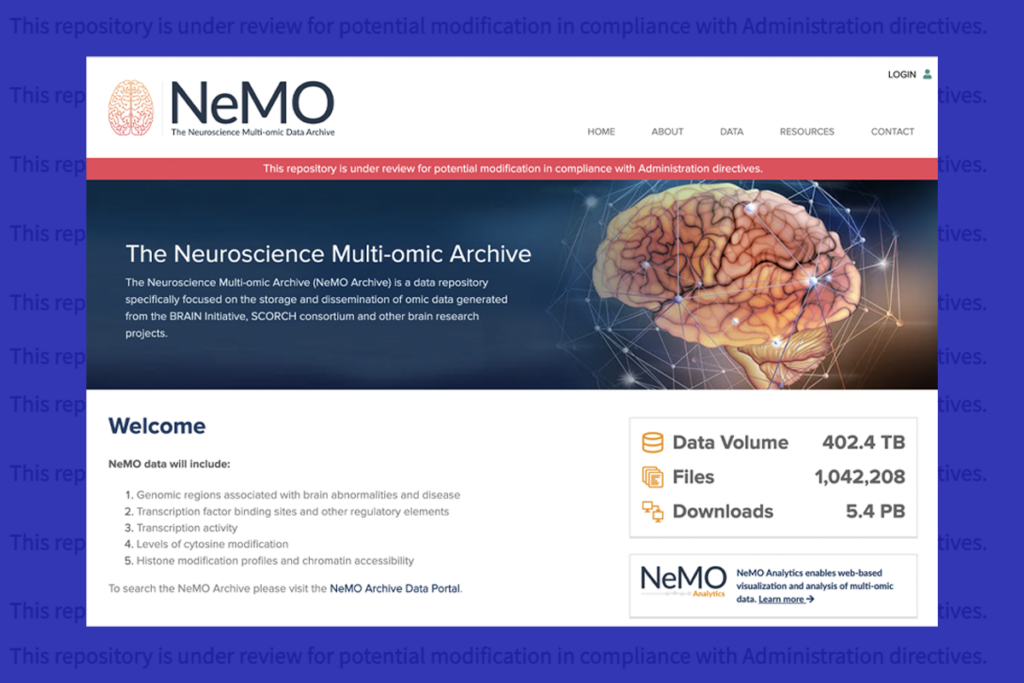

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors