Repetitive behaviors in autism show sex bias early in life

Girls with autism may have less severe restricted and repetitive behaviors than do boys on the spectrum.

Girls with autism have slightly less severe restricted and repetitive behaviors than do boys on the spectrum, according to one of the largest studies of sex differences in children with the condition1.

The difference is small and is seen only in children aged 5 and younger. Boys and girls older than 5 have repetitive behaviors of comparable severity, and children of all ages show similar social communication skills.

About four times as many boys as girls are diagnosed with autism. As a result, there is little information about how the condition might present in girls.

The new study is based on 2,684 people with autism from nine countries in Europe. It confirms the results of smaller studies — and of one large study of people with autism in the United States2. These studies also found that girls with autism are less likely to have restricted interests than are boys on the spectrum.

“That’s one of the more consistent sex differences that have emerged,” says co-lead investigator Tony Charman, chair of clinical child psychology at King’s College London.

One strength of the new study is that it includes nearly 500 girls with autism, orders of magnitude more than in other work.

“We keep looking for sex differences, and it’s a tricky business because we find so many fewer females than males in research samples,” says Catherine Lord, director of the Center for Autism and the Developing Brain at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. “What’s really nice about this study is they had such a large sample that they could have more girls.”

Parent gap:

Between 2015 and 2017, Charman and his colleagues contacted 100 sites within a consortium called the European Autism Intervention – A Multicentre Study for Developing New Medications (EU-AIMS). The network compiles data about people with autism from 37 European countries.

The study looked at 2,220 boys and men and 464 girls and women. Nearly half of the participants were younger than 6 years, 1,133 were between ages 6 and 18 years, and 415 were older than 18.

Researchers at 18 sites provided scores for most participants on two gold-standard diagnostic tests — the clinician-led Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and a parent questionnaire called the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R).

The ADI-R asks the parents to assess their children’s behaviors, including restricted and repetitive behaviors, over time.

On average, parents gave a slightly higher severity score for restricted and repetitive behaviors to boys aged 5 or younger than to girls of that age. This association does not hold in older children, or in scores on the ADOS, which measures behavior only at the time of testing. The results appeared in February in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

The sex difference is not statistically significant if the researchers control for the participants’ nonverbal intelligence quotients. However, that calculation involves data from only 1,283 of the participants because intelligence scores for the others were not available, says Julian Tillmann, a postdoctoral researcher in Charman’s lab.

Still, this caveat doesn’t detract from the results, experts say.

“I don’t think this weakens the study,” says Donald Oswald, director of diagnostics and research at Commonwealth Autism in Richmond, Virginia.

Collecting dolls:

The sex difference is particularly compelling because the children are likely to be similar to one another, based on their criteria for inclusion in the study.

The researchers included only individuals with an autism diagnosis and qualifying scores on the ADOS and ADI-R, says Kevin Pelphrey, director of the Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Institute at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the work.

“Given that naturally kids are going to be more similar if they met a diagnostic cutoff for inclusion, then it’s even more surprising when you see a significant difference,” he says.

The findings may reflect parents’ lack of awareness about how autism presents in girls.

Some parents may not recognize restricted interests in their daughters because their interests are similar to those of typical girls, Charman says. For instance, girls with autism may collect dolls obsessively rather than play with a doll as a typical girl might.

The ADOS and the ADI-R, which are primarily based on research in boys with the condition, may similarly fail to pick up such subtleties.

“It’s probably about time for an update on these instruments,” Oswald says.

Charman’s team plans to evaluate individual questions in the tests to better understand the sex differences the tests pick up.

References:

Recommended reading

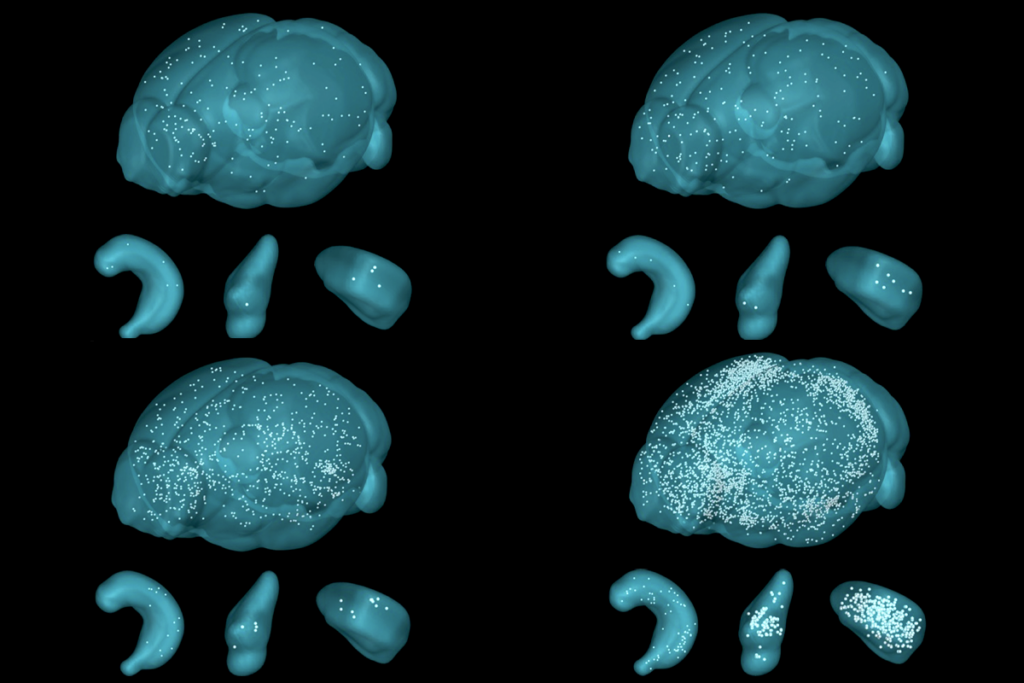

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky