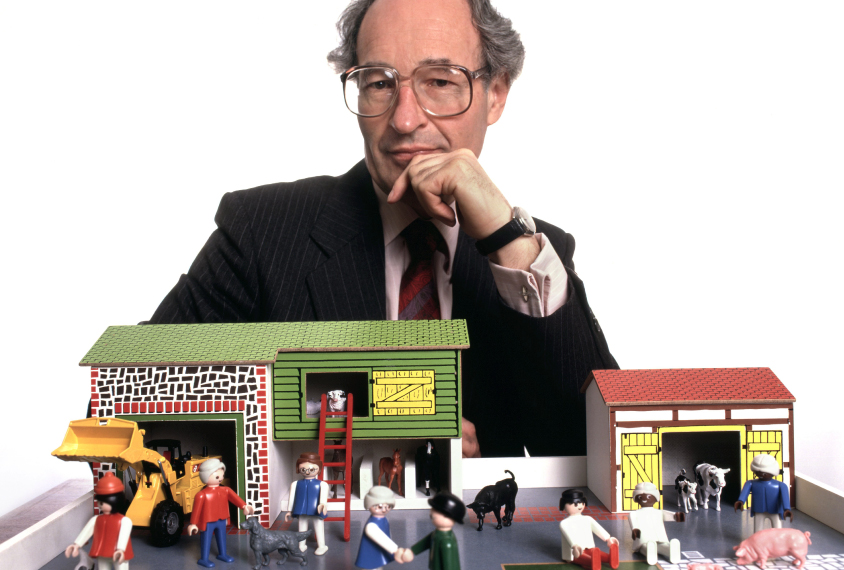

Sir Michael Rutter, the child psychiatrist who overturned outmoded ideas about autism’s origins, died 23 October at age 88. In July, Rutter had retired from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King’s College London in the United Kingdom, where he had worked for 55 years.

During that time, Rutter co-authored a landmark 1977 study of autistic twins, which established that genetic factors play an important role in the condition. His work helped dispel the myths that autism was a childhood form of schizophrenia or could be credited to particular parenting styles. In the latter half of his career, Rutter also focused on the challenges autistic people experience as they get older — a long-overlooked area of autism research.

Many of the people Rutter diagnosed with autism as children are now in their 60s and 70s, and they still remember how different his approach was compared with that of his contemporaries, says his longtime collaborator Patricia Howlin, professor emeritus of clinical child psychology at King’s College London.

“These are autistic adults who acknowledge how much they owe him, particularly going back to a time when there was very little support and very little understanding, either of the autistic children and adolescents themselves, or their families,” Howlin says. “It’s not just a loss to the academic world.”

Rutter’s commitment to the autistic community extended beyond the usual bounds of a clinician, says Emily Simonoff, professor and head of child and adolescent psychiatry at King’s College London.

“Mike continued to provide advice and oversight for many years to autistic children whose needs as adults were not well met by adult mental health services.”

Within the academic community, Rutter’s sway extended around the world. Clinical psychiatry trainees regard his 1981 textbook “Child and Adolescent Psychiatry” as “the bible,” says Meng-Chuan Lai, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto in Canada. “I was trained as a clinician in Taiwan, so his influence is global. It’s not restricted to the English-speaking world.”

The textbook not only laid the foundation for the field, but urged readers to question conventional wisdom, Lai says — an approach that extended to his clinical training work.

“Mike challenged trainees to read widely, think critically and organize their ideas into tractable scientific questions,” Simonoff says. “His standards for scientific quality were always of the highest level, and he discouraged trainees and colleagues from settling for anything less than this in their own work.”

Clinical emphasis:

Rutter’s work focused, first and foremost, on the clinic, where he was intent on helping parents and teachers foster autistic children’s development. In the early 1970s, when many clinicians were primarily interested in the difficulties such children can encounter, Rutter emphasized the exceptional memory, motor, musical and mathematical abilities that some possess, Howlin says.

“One of his particular legacies was identifying the benefits of having autism, rather than just always focusing on the things that children couldn’t do,” she says.

This tendency to buck convention defined Rutter’s career. He brought a methodological rigor to his practice and stressed the importance of reliable measurement — something that had previously been missing from psychology and psychiatry, says Eric Fombonne, professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, who worked with Rutter starting in the 1980s. “He’s been the person who established our field as a scientifically oriented discipline. It was not before him, and now it is.”

Not one to rest on his laurels, Rutter always tried to debunk his own work, Fombonne says, questioning the nature of scientific knowledge, asking how scientists can know what they know and devising what the next steps should be to investigate a research question.

“He was keen on obtaining the best measurements possible,” Fombonne says. “He was always paying a lot of attention to the quality and validity of our measurements.”

To that end, Rutter helped to develop two gold-standard diagnostic tools for autism — the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview — in collaboration with Catherine Lord, distinguished professor of psychiatry and education at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“He really prided himself on his collaborations,” Lord says. “Almost everything he did involved collaboration.”

When they worked together on the ADOS, a clinical tool that involves playing with young children, the somewhat formal Rutter was a bit out of his element, Lord says. Nonetheless, he had good ideas about how to gather the best possible data. “He really insisted on trying to get people to be reliable and tried to make the information as meaningful as possible,” she says.

Range and rigor:

In the late 20th century, when many psychiatry researchers were siloed into their disciplines, Rutter made several forays beyond autism. He studied genetic influences on development and weighed in on educational policies. In his Isle of Wight studies, he conducted epidemiological research on a range of psychiatric conditions and behavioral issues.

“That’s a remarkably rich tapestry that very few people have,” says Tony Charman, professor of clinical child psychology at King’s College London. “For lots of us, if we do work on autism and [attention deficit hyperactivity disorder], we consider ourselves quite a varied scientist.”

One of Rutter’s most well-known contributions outside of autism was his work with Romanian orphans who had been deprived of caretaking as infants in the 1980s and 1990s. He tracked their development and showed that quicker adoption led to improved developmental outcomes.

Charman peer-reviewed one of Rutter’s manuscripts about the orphans and objected to the use of the term “quasi-autistic” to describe some of their clinical characteristics.

Rutter was always willing to change his mind when presented with new evidence, Charman says. “Some people who are very eminent can be iconoclastic.” At the same time, though, “if he disagreed with the comments from reviewers or editors, he would quite robustly defend his view.”

After a “robust” debate, Charman says, the term made it into the final publication.