Regional autism rates point to impact of awareness, training

The odds of getting an autism diagnosis depend on where in the United States a person lives.

Children’s odds of getting an autism diagnosis depend on where they live in the United States, according to a new study1. The variation persists after controlling for a family’s socioeconomic status and certain environmental factors, suggesting that it reflects differences in access to medical care.

“It is perhaps more likely that aspects of getting diagnoses and care may be stronger drivers of the patterns we saw,” says Marc Weisskopf, professor of epidemiology at Harvard University.

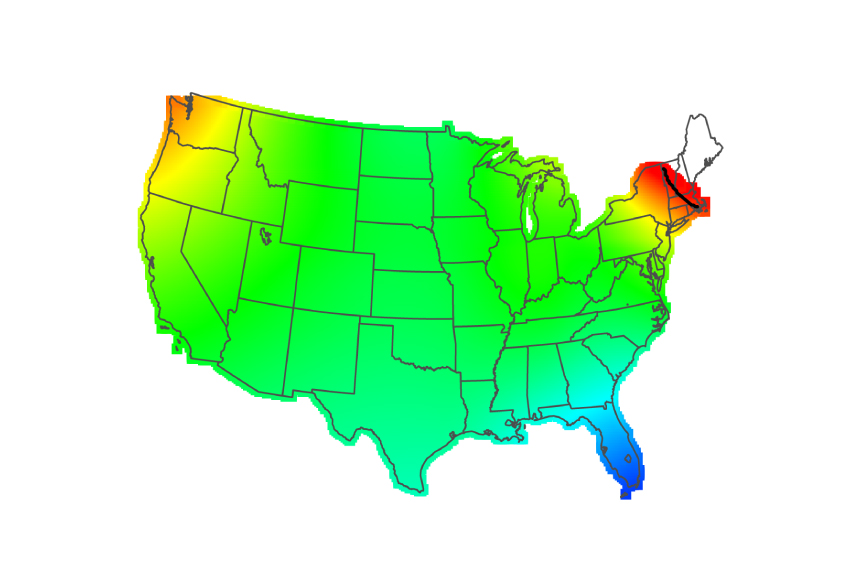

Children born in New England and Indiana have relatively high odds of receiving an autism diagnosis, whereas those living in the southeastern U.S. have low odds.

“If you have a child with autism in Mobile, [Alabama,] you are less likely to have him or her recognized and diagnosed than if you live in Boston,” says Eric Fombonne, professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University, who was not involved in the study.

The new findings confirm previous reports of geographical variation in autism prevalence. A 2008 survey by the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, which gathers data from 14 sites across the U.S., found a low prevalence in Alabama and the highest in New Jersey.

Areas of the country with apparently low rates of autism may need more qualified doctors and higher levels of funding. “When you put efforts into care provision, you see that the kids are there,” Weisskopf says.

The results also support the idea that the increase in autism over the past two decades is largely due to growing awareness and better training of doctors.

The prevalence of autism has risen from 1 in 150 children in 2000 to as high 1 in 45 in 2015. Studies that explore geographic patterns of autism may clarify how much of the increase is due to awareness and better diagnostic practices versus biological and environmental causes.

Big differences in autism rates could hint at the influence of an environmental factor — for instance, societal resources — that is more abundant in some areas than in others.

Mapping autism:

The researchers examined data from thousands of mothers and their children from The Nurses’ Health Study II, a long-running investigation into the risk factors for chronic diseases in women.

In this study, nurses complete questionnaires every two years about their health and that of their children. The data include nearly 35,000 children born between 1989 and 1999 in 48 states. In 2005, the survey asked nurses if any of their children had been diagnosed with autism.

A total of 586 children had received an autism diagnosis. The researchers looked at autism rates based on address at birth, which would reflect any effect of exposure to any risk factors in the womb.

The team included only singleton births and children without known genetic syndromes. They also included only one child from each family to prevent an apparent geographical clustering of cases that may result from genetics. The final analysis included 13,507 children, 486 of whom have autism.

At one extreme, children born in New England are about 1.5 times more likely than those born in the U.S. as a whole to be diagnosed with autism. By contrast, children born in the southeastern U.S. are about half as likely as the U.S. average to receive an autism diagnosis. An analysis using addresses at age 6 yielded similar results. The study was published 19 May in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

Healthcare cracks:

Controlling for the mother’s age, child’s gender and socioeconomic status has no impact on the results. The researchers also found no link between autism and exposure to hazardous air pollutants, such as lead, mercury and other metals found in diesel exhaust.

The most likely explanation for the differences in prevalence, researchers say, is the level of care a given region provides.

“The differences most likely reflect low-resource communities that do not get the services and screening that high-resource communities do,” says Irva Hertz-Picciotto, professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the study.

A case in point: The data revealed elevated autism rates in Indiana, the first state to require insurance coverage for autism care. The policy makes people more likely to seek the services they need.

On the flip side, autism prevalence may be higher than statistics suggest in communities in which appropriate care is difficult to obtain. “If policies aren’t in place to help them, then they may fall through the healthcare cracks,” Weisskopf says.

Definitively identifying the reasons behind geographic variation in autism rates will require further study with larger datasets, says Weisskopf. He and his colleagues are conducting a similar study in Israel that includes several thousand people with autism.

References:

- Hoffman K. et al. Am. J. Epidemiol. Epub ahead of print (2017) PubMed

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt