Rat model mimics communication problems in Angelman syndrome

Rats missing UBE3A, the gene mutated in people with Angelman syndrome, squeak frequently but tend not to be responsive to the play and squeaks of other rats.

Rats missing UBE3A, the gene mutated in people with Angelman syndrome, squeak frequently but tend not to be responsive to the play and squeaks of other rats.

Angelman syndrome is characterized by autism, developmental delay, speech problems and seizures.

The rats’ behavior is strikingly similar to that of people with the syndrome, supporting the idea that rats are more realistic models of human social interactions than are mice.

“We were able to discover a clear and robust Angelman phenotype that could potentially be used in screening and testing potential therapeutics,” says Elizabeth Berg, a graduate student in Jill Silverman’s lab at the University of California, Davis. “Our results provide important evidence for the role of UBE3A in social behavior and communication.”

Berg presented the findings today at the 2019 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago, Illinois.

The researchers created rats missing the maternal copy of UBE3A. They first tested how juvenile mutants respond to social contact by tickling them while recording their ultrasonic squeaks. Much like people, rats generally experience tickling as a positive sensation and respond by vocalizing.

Tickle me:

Rats with the mutation vocalize three times more frequently than control animals do in tickle sessions, as well as during brief tickle-free periods beforehand, the team found.

The finding aligns with the behavior of people with Angelman, who tend to laugh often — and sometimes without a clear reason, Berg says.

The researchers then watched how the rats interact with a playmate. Typical juvenile rats might pounce on each other up to 10 times over 10 minutes. The mutant rats approach and sniff their buddies as expected, but they show no interest in chasing them or engaging in rough-and-tumble play.

“We interpreted this as reduced species-typical social behaviors at the juvenile age,” Berg says. “Kids with Angelman syndrome are interested socially, but their interactions are very atypical.”

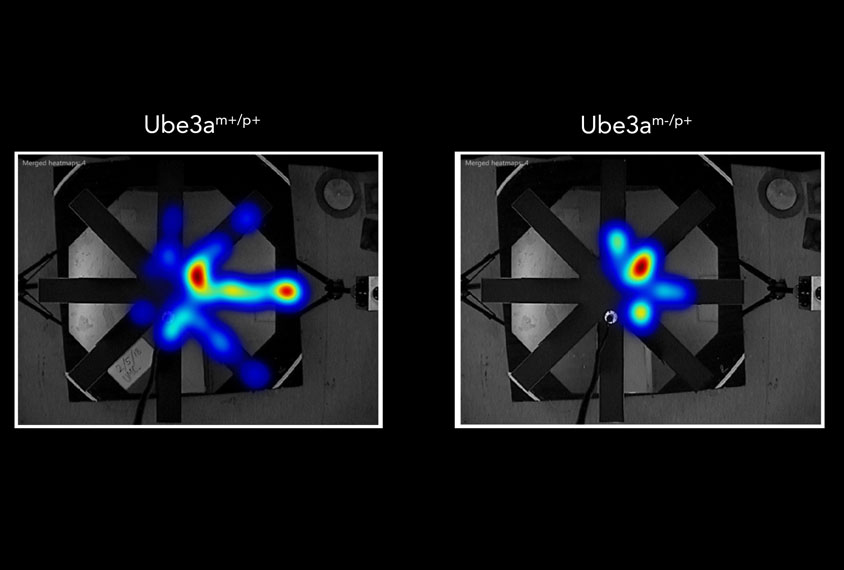

Finally, the researchers assessed how the mutant rats respond to vocalizations made by other rats. They released the rats into a maze and played a recording of another rat’s ultrasonic squeaks. Control animals follow that sound all the way down the maze. The mutant rats explore the maze just as readily, but they are much less active in seeking out the source of the recorded rat call.

For more reports from the 2019 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models