Rat model of autism shows unusual brain growth at birth

The brains of rats exposed in utero to the seizure drug valproate show a significant increase in brain size around the time of birth.

The brains of rats exposed in utero to the seizure drug valproate show a significant increase in brain size around the time of birth, a new study suggests1.

Rats exposed to valproate in this way are used as a rodent model of autism. The study is the first to explore how brain structure changes during birth in an autism model. The researchers say the finding may help explain the brain enlargement seen in up to 20 percent of autistic children.

“This [enlargement] might already be the case at birth,” says lead investigator Yehezkel Ben-Ari, president and co-founder of Neurochlore, a biotech firm in Marseille, France. The findings appeared Wednesday in Science Advances.

But this idea has drawn significant skepticism from other experts. They say they do not dispute the data as presented but take issue with the interpretation.

“[Ben-Ari and his team] seem to want to tie their data to this phenomenon of early brain overgrowth, but I don’t think that it has any relationship to that,” says Konstantinos Zarbalis, associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of California, Davis. “Their brains are not really larger at birth; it’s just that before birth they’re smaller, and they catch up during this 24-hour window of birth.”

“I think that observation alone is kind of interesting,” says Anis Contractor, professor of neurobiology at Northwestern University in Chicago, of the changes around birth. “But it would have been nice to have multiple rodent models, because that might give more support that this is really important to the autism phenotype.”

Shape shifting:

Ben-Ari and his colleagues focused on birth because of their earlier work showing that labor is accompanied by a switch in the function of a chemical messenger implicated in autism.

The messenger, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), boosts brain activity in fetal rodents. But typically, a surge of the hormone oxytocin during labor causes GABA to suppress brain activity instead. In a 2014 study, Ben-Ari’s team showed that this switch doesn’t happen in valproate-exposed rats; in those rats, GABA remains excitatory at birth.

“Birth is a huge stress for the baby, or the young rat,” Ben-Ari says. “If you have excitatory GABA on top of this huge stress, my suggestion is this can be toxic.”

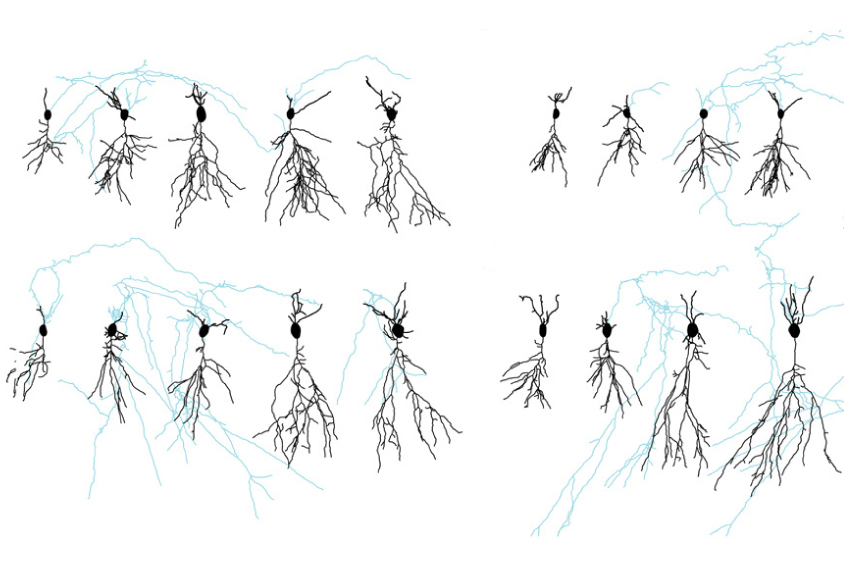

The team exposed fetal rats to valproate on day 12 of gestation. They obtained brain slices from some of these fetal rats the day before birth, and from others on the day of birth. They examined the shape of neurons in brain slices from the hippocampus, a brain region involved in learning and memory.

Neurons in the rats analyzed at birth have longer branches, called dendrites, than those analyzed before birth, the researchers found. By contrast, neurons in controls show no shape changes.

These data are “quite convincing,” says Nicolas Renier, principal investigator at the Brain and Spine Institute in Paris, who was not involved in the work. “It would be interesting to elucidate the cellular mechanism that leads to this outgrowth.”

Ben-Ari says the neurons in valproate rats may lengthen because excitatory GABA fosters neuron growth, though this idea remains untested.

Switching back:

His team also compared the volume of the rats’ brains before and after birth. They used a technique called iDISCO to make the tissue transparent, allowing them to look for volume changes in various brain structures.

The hippocampus and cerebral cortex of the valproate-exposed rats both increase in volume in the period surrounding birth, they found. These structures in controls show no changes in size.

However, the brains of the valproate-exposed rats are smaller before birth than those of controls. So after birth, the structures are the same size in the two sets of rats.

The findings should be confirmed using magnetic resonance imaging, which is a more reliable way to measure changes in brain volume than iDISCO, Renier says.

In the 2014 study, Ben-Ari’s team showed that giving pregnant rats the blood pressure drug bumetanide just before delivery corrects the faulty GABA switch. In the new study, they found that the drug also prevents the changes in brain volume.

Experts question whether the GABA switch mediates these effects, however. Bumetanide is a diuretic, and the changes in brain volume could simply reflect the drug’s ability to shrink cells by decreasing their water content, they say.

“It could be that bumetanide has a different effect, not really involving GABA,” says Enrico Cherubini, scientific director of the European Brain Research Institute in Rome, who was not involved in the study.

Ben-Ari’s team is examining neurons in other brain regions besides the hippocampus for size changes at birth. They are also looking for birth-related brain changes in two other rodent models of autism: a mouse model of fragile X syndrome and mice exposed to maternal inflammation in the womb.

References:

- Cloarec R. et al. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav0394 (2019) Abstract

Recommended reading

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Home makeover helps rats better express themselves: Q&A with Raven Hickson and Peter Kind

Explore more from The Transmitter

Frameshift: Shari Wiseman reflects on her pivot from science to publishing

How basic neuroscience has paved the path to new drugs