Psychotropic drugs frequently prescribed for autistic people

About one in three autistic people in the United Kingdom is prescribed drugs designed to alter brain function.

About one in three autistic people in the United Kingdom is prescribed drugs designed to alter brain function, based on the records of almost 40,000 people1.

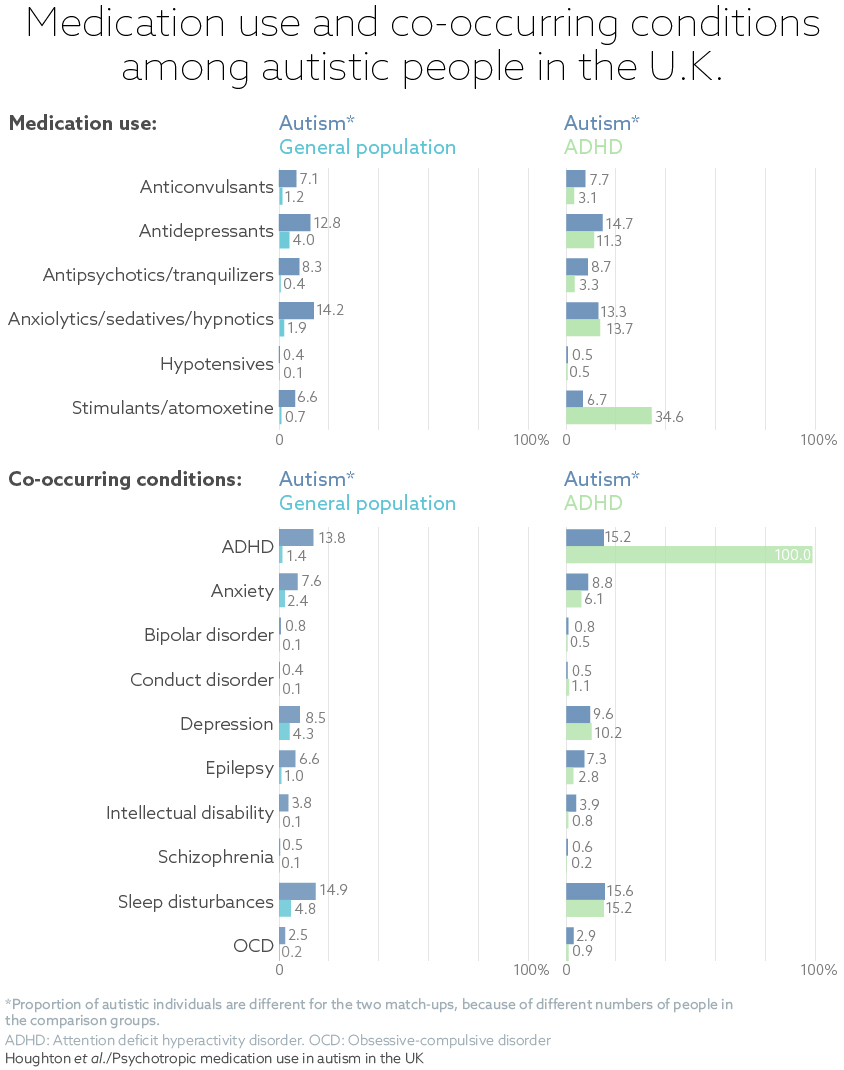

People with autism are more likely to be prescribed these so-called ‘psychotropic’ drugs than are most people who visit a doctor. The figure for autism is almost as high as it is for people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), for whom some of these drugs are approved treatments.

The likelihood of medication use among people with autism increases with a person’s age and number of co-occurring psychiatric conditions, according to the study. Yet about 14 percent of autistic people without any of these conditions get the prescriptions.

There are no approved drugs for autism’s core features, so doctors may be prescribing the drugs for off-label use, the researchers say.

“Increasing age and the extra mental-health comorbidities, they’re all increasing the likelihood of receiving the medications, but they don’t explain all of the treatment use,” says lead investigator Richard Houghton, data scientist at the Switzerland-based pharmaceutical company Roche, which funded the study. The company is testing a drug that may ease some aspects of autism.

Graph by Nigel Hawtin

Most of the work that’s been done in this area has been done in the United States, says David Mandell, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the study. “It’s nice to see something coming out of other countries about prescribing.”

The proportion of autistic people using the medications mirrors that reported in a 2014 study of 5,651 autistic individuals in the United Kingdom2. Autistic people in the U.S. may be prescribed psychotropic drugs at even higher rates: A 2014 study suggests that two out of three people with autism in the U.S. take the drugs3.

Drug disconnect:

Houghton’s team analyzed the medical records of more than 10,800 people with autism, 7,000 people with ADHD and 21,700 controls, all matched for age, sex and geographic location. The records come from a U.K. national database; they detail psychiatric diagnoses and psychotropic prescriptions made by primary-care doctors.

About one-third of people with autism have received prescriptions for psychotropic drugs, compared with 6.5 percent of controls and 47.5 percent of people with ADHD, the researchers found. About 10 percent of people with autism and 11 percent with ADHD have been prescribed more than one medication, compared with less than 1 percent of controls.

As much as 45 percent of autistic people have a co-occurring psychiatric condition, compared with 29 percent of people with ADHD and 12 percent of controls.

The medications prescribed to autistic individuals do not precisely match their psychiatric diagnoses; they are most commonly prescribed depression and anxiety drugs, but their most frequent co-occurring conditions include sleep disturbances and ADHD. The work appeared in December in Autism Research.

The relative lack of prescriptions for these co-occurring conditions is concerning — especially for ADHD, given that it is one of the most common comorbidities in children with autism, says Evdokia Anagnostou, senior clinician scientist at the Bloorview Research Institute in Toronto, Canada, who was not involved in the study. That said, specialists might be treating some of the children who have both autism and ADHD, and pediatricians might sometimes recommend over-the-counter drugs for sleep problems. (The study does not account for either of these possibilities.)

The mismatch between diagnoses and prescriptions could also result from treating traits or problems divorced from diagnoses. “It’s possible that a lot of the family doctors just go ahead and treat symptoms without bothering to add diagnostic labels,” Anagnostou says, referring to the prescriptions for depression and anxiety in autism.

Boys and men with autism have about 26 percent lower odds of taking a psychotropic drug than girls and women with the condition. This might be because females tend to be more severely affected or because they are more likely to consult a doctor.

Houghton and his colleagues have also looked at the use of behavioral therapies in the U.S. In a study published in January, they reported that 96 percent of autistic children have received at least one intervention, most often speech and language therapy or occupational therapy4. Children living in rural areas typically receive fewer of these therapies and have fewer therapy hours than those from urban areas.

References:

Corrections

This article has been modified from the original. A previous version incorrectly stated that girls and women with autism are about 26 percent more likely than boys and men with the condition to take psychotropic drugs.

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

This paper changed my life: Shane Liddelow on two papers that upended astrocyte research

Dean Buonomano explores the concept of time in neuroscience and physics