Prozac during pregnancy alters mouse pup behavior

Pregnant mice exposed to the antidepressant fluoxetine have pups with autism-like behavioral impairments.

Pregnant mice exposed to the antidepressant fluoxetine (marketed as Prozac) have pups with behavioral impairments reminiscent of those seen in autism. Researchers presented the unpublished results today at the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago.

Epidemiological studies suggest that taking a class of antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) while pregnant increases the risk of having a child with autism.

“We wanted to model this in a mouse to understand the extent to which SSRIs may cause autism-related behaviors and to try to find a mechanism that may be mediating those behaviors,” says Susan Maloney, a postdoctoral fellow in Joseph Dougherty’s lab at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, who presented the work.

Maloney and her colleagues exposed pregnant mice to fluoxetine at doses analogous to those used in people with depression. They continued to feed the mice fluoxetine in their drinking water after they gave birth so that the drug would also be present in their milk.

The researchers then performed a series of behavioral tests on the pups. They first measured ultrasonic vocalizations — the barely audible squeaks that pups make when separated from their mothers. Studies have found that some mouse models of autism make fewer squeaks than controls do.

Pups born to mothers exposed to fluoxetine during pregnancy make fewer and briefer squeaks than those born to mothers who had no exposure to the drug, the new study found.

Prozac puzzle:

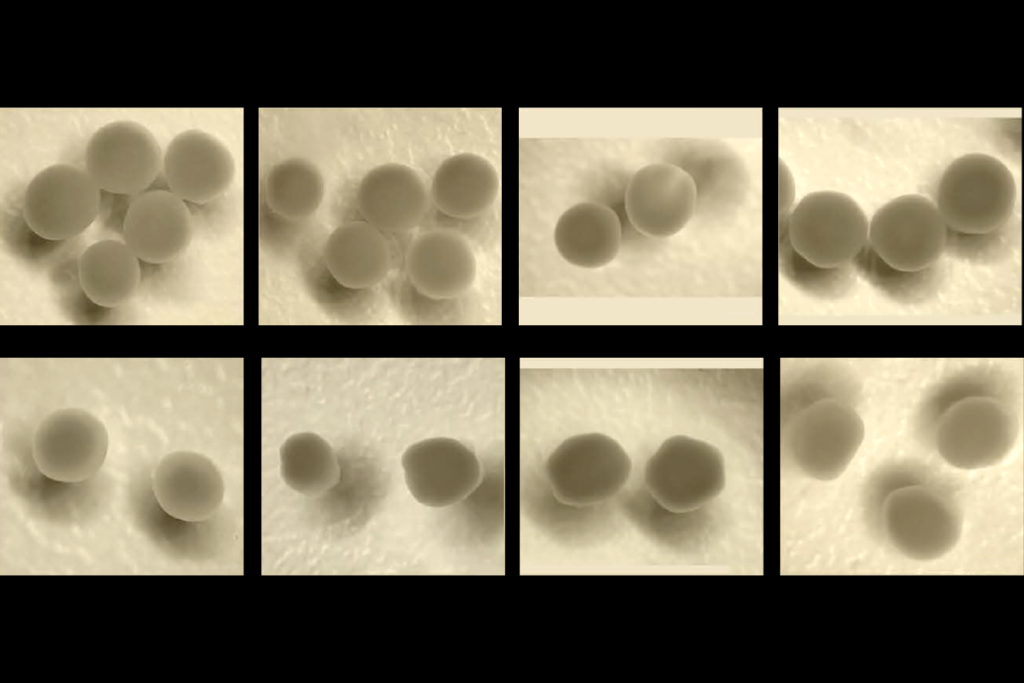

The researchers also used a T-shaped maze to measure restricted interests — a core feature of autism. Ordinarily, pups explore both arms of the T equally. By contrast, pups born to fluoxetine-exposed mice tend to favor one arm over the other, repeatedly returning to that same side.

“It’s a very robust behavioral phenotype,” says Maloney.

However, pups born to fluoxetine-exposed mice differ from mouse models of autism on the marble-burying test, which measures repetitive behaviors. Unlike autism mice, which tend to bury more marbles than controls, fluoxetine pups bury fewer.

“If you directly administer SSRIs to mice, you also see a decrease in marble burying,” says Maloney. “This suggests the drug may be having an [anxiety-relieving] effect.”

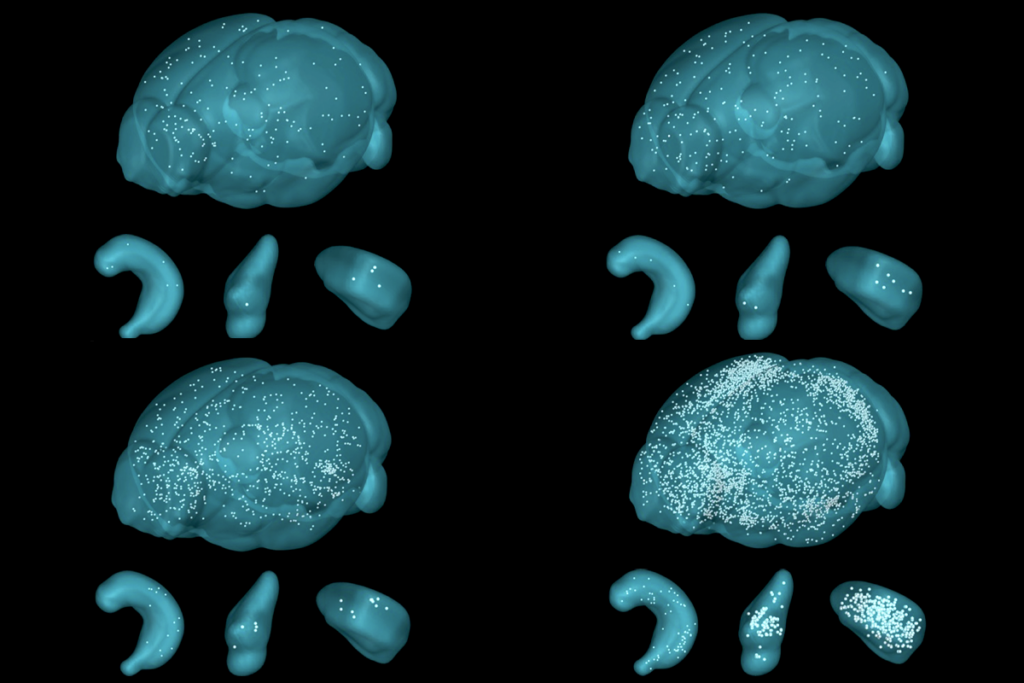

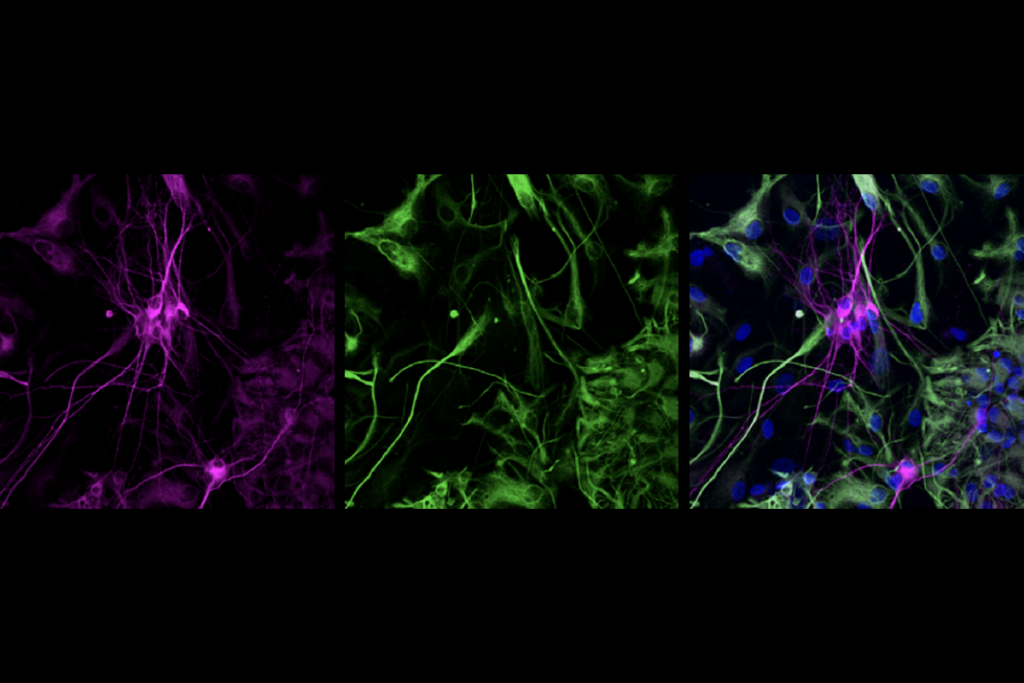

To uncover a possible mechanism for the pups’ atypical behavior, Maloney and her colleagues looked at gene expression in the pups’ forebrains. They started with seven genes, some of which are involved in excitatory and inhibitory brain signaling, which is thought to be imbalanced in autism. They also looked at the gene encoding a serotonin receptor.

They have yet to find any significant effects of fluoxetine exposure in the womb on gene expression, but they plan to sequence a larger collection of genes using a technique called RNA-seq. They also plan to test aggression and sociability in the mice and to look at the effects of SSRI use in the first trimester of pregnancy.

For more reports from the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky