Protein linked to autism may help birds learn songs from elders

Turning down the expression of a gene linked to autism leaves zebra finches singing disorganized songs.

Turning down the expression of a gene linked to autism leaves zebra finches singing disorganized songs. The results suggest the gene, FOXP1, is involved in social aspects of language learning.

Researchers presented the unpublished findings Sunday at the 2019 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago, Illinois.

FOXP1 has been implicated in both language problems and autism, says Therese Koch, a graduate student in Todd Roberts’ lab at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

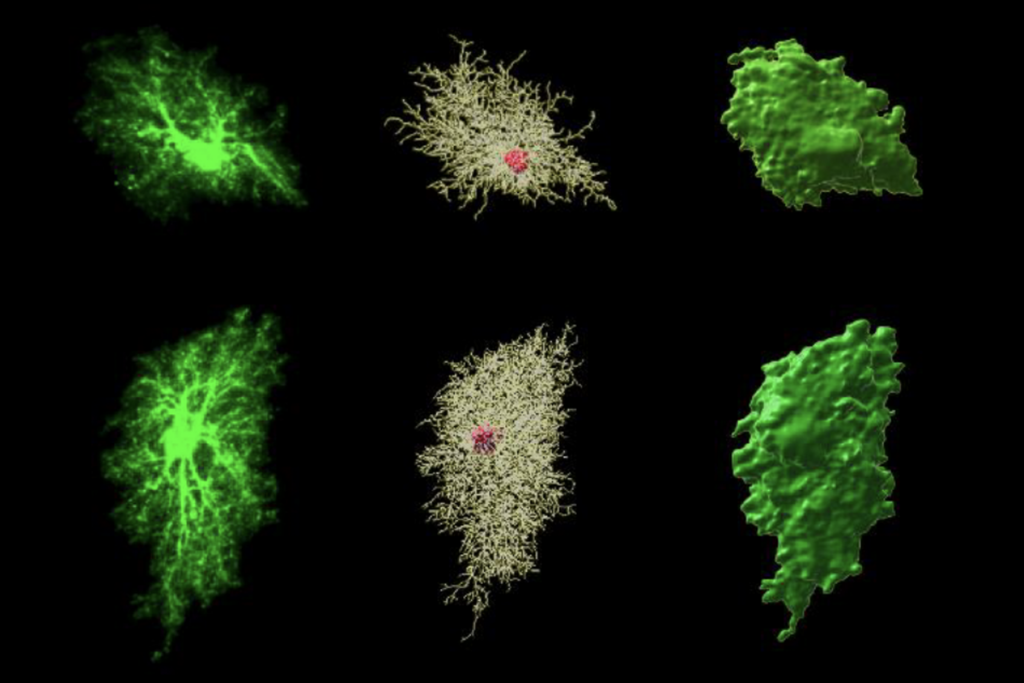

In zebra finches, most of the neurons that connect two song-related brain regions, called HVC and area X, express FOXP1, the team found. The researchers injected a molecule that lowers FOXP1 expression in the HVC region.

Male zebra finches normally learn to sing by listening to and imitating the songs of adult birds, much as babies learn to speak. Song learning in these birds takes place during the first 90 days of a bird’s life.

The researchers injected 35-day-old male birds with the molecule and then put them in a cage with an adult male ‘tutor.’ Birds that had been tutored prior to the injection grew up to sing the typical zebra finch song, which has a highly structured, consistent pattern of notes.

But birds that had been raised in isolation before the injection grew up to sing songs composed of simple notes strung together in variable ways. Their songs resemble those of birds that never hear song in their first 90 days of life, “which is really remarkable,” Koch says.

The findings suggest that FOXP1 is important for the birds’ ability to learn songs from adults. Studies have suggested that other autism-linked genes, such as CNTNAP2, may also facilitate this learning.

Broken record:

The researchers tested this theory with pairs of male finches from the same clutch. When the birds were about 30 days old and had already had ample exposure to their father’s song, the researchers knocked down the level of FOXP1 in one bird from each pair and then moved both to a cage with a new adult male.

The brother with a low level of FOXP1 wound up singing a song similar to his father’s, but the other bird learned and incorporated elements from the new male’s song.

“It seems like the FOXP1 knockdown is cutting off the ability to learn from the tutor,” says Francisco Garcia-Oscos, an undergraduate working in Roberts’ lab.

FOXP1’s effect on song learning may relate specifically to neurons that connect HVC to area X, Garcia-Oscos says.

The researchers found that in these neurons, birds with low FOXP1 levels have an altered ratio of two sets of receptors thought to play a role in learning.

For more reports from the 2019 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Profiles of neurodevelopmental conditions; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

How artificial agents can help us understand social recognition

Methodological flaw may upend network mapping tool