Positive autism screening results rarely prompt follow-up

Most toddlers who screen positive for autism do not receive the recommended referrals for follow-up tests or therapies.

Most toddlers who screen positive for autism do not receive the recommended referrals for follow-up tests and therapies, a new study of nearly 4,500 children suggests1.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that doctors screen all children for autism starting at 18 months of age and refer children with positive test results to an autism specialist for further evaluation, to an audiologist for a hearing test and to early-intervention services for therapy2.

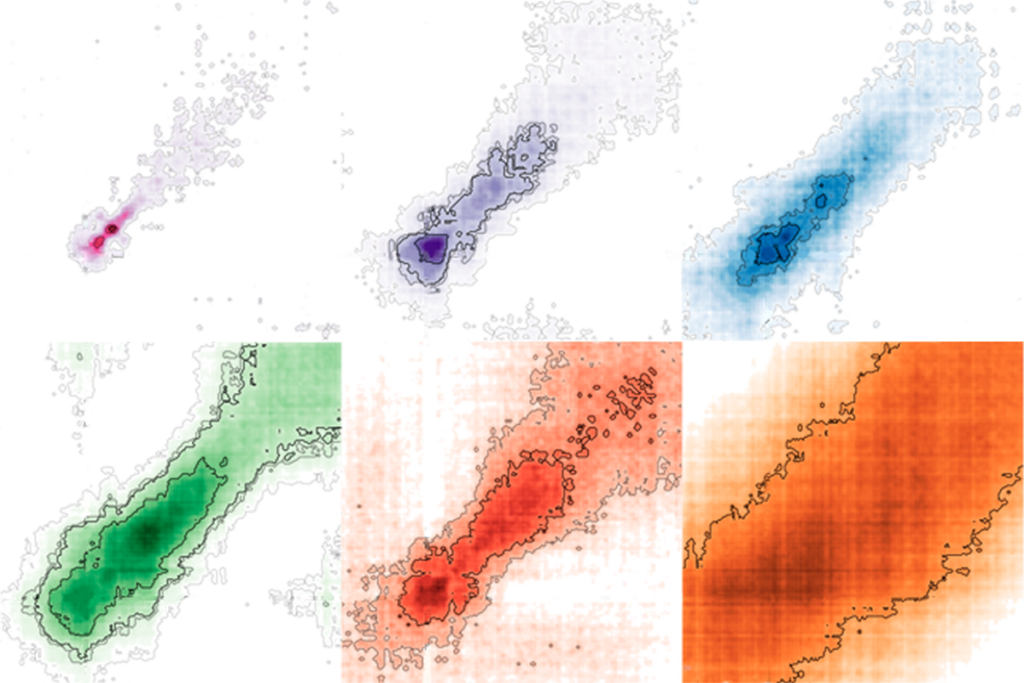

Those three referrals happen for only about 4 percent of children flagged by a popular autism screening tool during routine doctor visits, the new work shows.

“What this study shows is that people are not following [autism screening guidelines], at least with regard to referral-making,” says Katharine Zuckerman, associate professor of pediatrics at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t matter if you screen everybody if you don’t refer anybody when you have a positive screening-test result.”

Doctors appear to refer only some children for some services, depending on the child’s sex, race and other characteristics, says co-lead researcher Kate Wallis, developmental behavioral pediatrician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania. For example, her team found that clinicians are less likely to refer girls than boys for early intervention.

“We have to find ways to improve referral rates so that all children can be evaluated and begin in therapy services,” Wallis says.

Clinical considerations:

Wallis and her colleagues analyzed electronic health records from routine visits to 31 primary care clinics in Pennsylvania and New Jersey from 2013 to 2016. Doctors at these clinics screen all toddlers for autism when they are 16 to 30 months old, using a standardized questionnaire for parents called the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT). Doctors are supposed to do a follow-up interview with the parents of any child whose scores indicate a “moderate risk” and then decide whether the child has screened positive or negative.

The researchers found 4,442 children whose M-CHAT scores warranted a follow-up interview with their parents. But that interview took place for less than half of them, or 1,660 children. Doctors did not do an interview for 63 percent of children, including 473 who scored so high that no interview was needed need to confirm the results.

Of the children whose parents had follow-up interviews, doctors determined that 1,560, or 94 percent, had screened negative. This may indicate that clinicians do follow-ups mainly when they suspect false positives. False positives are a known issue with the M-CHAT, and the follow-up interview is designed to weed them out.

Families with public insurance were among the most likely to receive a follow-up interview. Clinicians may be more likely to refer children for a follow-up interview when they know a family’s insurance will cover it — as most public insurance does, the researchers say. The findings were published in May in PLOS One.

The results highlight a need to understand what drives decision-making after a positive autism screen, Wallis says. “Some pediatricians may not trust the results of the screen, they may have other competing health priorities to address during the visit, or they may not want to worry parents if they are unsure if a child has [autism].”

Addressing disparities:

The team further analyzed the referrals for 2,882 children with a positive screen: About 11 percent were referred to specialists for a comprehensive autism evaluation, and about 11 percent were referred to an audiologist. Around 31 percent were referred to early-intervention services; another 26 percent were already receiving early interventions.

The study shows that some underserved groups benefit in some ways from universal autism screening, says Tiffany Baffour, associate professor of social work at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, who was not involved in the study. For instance, Black children were more likely than white children to be referred to an audiologist, though they were less likely to be referred for early intervention.

But some families referred for early intervention or further screening refused to follow up, which raises new questions, Baffour says. To increase the value of universal screening, researchers need to identify the barriers, such as transportation or finances, that keep some families from referrals.

Wallis’ team plans to examine whether disparities in referrals after screening skew autism diagnosis and prevalence rates. To increase the number of pediatricians following clinical guidelines, they also plan to look at how clinicians make decisions about referrals for evaluation and treatment after a positive screening.

References:

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Let’s teach neuroscientists how to be thoughtful and fair reviewers

Two neurobiologists win 2026 Brain Prize for discovering mechanics of touch