In Peru, novel program paves the way for autistic people’s employment

At a center in Lima, Peru, people with autism learn to identify their strengths and find jobs that play to those strengths.

Like many working adults, Ronald Pesantes starts a typical day with a lengthy commute. His journey, which he makes four days a week, involves a taxi, the subway and a bus. It takes the 26-year-old about two hours to get from his home on the outskirts of Lima, Peru, to his job in the city.

“I feel I am a more independent person who helps his family and buys his things with his effort,” Pesantes says. “These things make me happy.”

But the road to employment for Pesantes, who has autism, was even more challenging. He didn’t speak until he was 9 years old, and throughout childhood, he often flapped his arms and threw tantrums. His behavioral problems as a young child earned him rejections from all three of the public schools his mother tried to enroll him in.

When Pesantes was 5, his mother heard about the Centro Ann Sullivan del Perú, a nonprofit organization in Lima named after Helen Keller’s teacher. The center’s staff teach children with autism and other developmental conditions the skills they need to live independently and secure jobs. They work with students starting from age 2 and extending well into adulthood.

Staff at the center also coach parents, siblings and grandparents to support the child in learning skills at home.

“We work in a team with families,” says Liliana Mayo, the center’s founder and director. “That is one of the keys of our program.”

Life skills:

Mayo founded the center in her parents’ garage in 1979, with two employees and eight students. The center now serves about 450 children and their families, and it has grown to a staff of 80. About 100 of those children, 60 percent of whom have autism, have gone on to find jobs at companies across Peru.

The center doubles as a regular school. Monday through Thursday, students learn to read and write and understand numbers, as well as use a fork and spoon, brush their teeth, dress themselves, cook and wash dishes, sweep and vacuum, and take public transportation. They also learn strategies to help them communicate their needs and desires — using picture boards if necessary.

Their teachers use praise to reinforce desired behaviors. Parents, and sometimes siblings and grandparents, attend weekly workshops at the center to learn how to be effective teachers, so that the learning continues in the home.

“We teach them with curriculum to prepare them for life,” Mayo says. “They are active members in their own home, learning basic things that are going to help them in the future.”

As they approach adulthood, students prepare a resume and practice job interviews. The center’s teachers help the students identify their strengths and find jobs suited to their abilities. Once a student lands a job, a teacher visits her in her new workplace daily for two weeks and coaches her on job skills. A parent or volunteer takes over as coach for the following six weeks. The student continues to check in with the center twice a month to learn additional skills, such as managing finances.

“Their focus on the strengths of individuals with autism is very important,” says Tele Tan, professor of civil and mechanical engineering at Curtin University in Perth, Australia. Tan founded and directs the Autism Academy for Software Quality Assurance, a program that teaches computer-programming skills to adolescents with autism and helps them gain professional experience as software testers.

Main breadwinner:

The center in Lima focuses on children who were born into families living in extreme poverty. Sandro López, who has autism, was one of the center’s first students. Now 37, López began studying at the center when he was 5. His family was so poor that when he was 8, he had to start making the hour-long bus trip from his home to the center unaccompanied.

Once López turned 15, he began working, with his parents’ consent, at the Wong grocery store chain in Lima. Five years later, in 2001, he landed a job at Alusud Peru, a company that makes plastic caps for food, drinks and other products. López works as an office assistant: He sorts and delivers mail, makes photocopies, enters data into a computer and delivers earplugs to workers on the factory floor. He remains employed by the company to this day.

López says he is glad to have a job that he can do well. “I have developed into an independent, productive and happy person,” he says. “I feel happy because I help my family and buy what I need with my labor.”

As the main breadwinner in his family, López pays for food and covers the utility bills. He obtained a bank loan to renovate his family’s home — adding a permanent roof and installing running water and electricity. When his father had a stroke in 2015, López covered the medical bills and treatments that otherwise would have been beyond the family’s reach, and he used his vacation allowance to help his father recuperate. He also covered the costs of his sister’s university tuition.

“What we are proving to the world is that they want the same opportunities,” Mayo says. “Instead of thinking that they are dependent, now they are independent, and now they are the ones taking care of their families.”

Inspiring others:

The program is so successful that Mayo and her colleagues have replicated it in Panama and the Dominican Republic, and they are helping others to establish similar centers in Ecuador, Argentina, Brazil, Bangladesh, India and Nigeria.

“She’s done a great job harnessing the parents,” says Merry Barua, founder and director of Action for Autism, a school for children with autism and their families in New Delhi, India. “That’s a very big part of what we do also; we believe very strongly in parent involvement.”

Within five years of starting at the center, Pesantes transitioned to an inclusive classroom at a private school. After a year, his mother could no longer afford the tuition there, but his outstanding grades won him a scholarship to continue. He graduated at the top of his class.

Like López, Pesantes found a job with the help of the center. In 2013, he began working for Prosegur Activa, a private security firm. Mayo says he soon became fixated on the idea of going to college to study accounting. His excellent grades garnered him one of three prestigious scholarships, which allowed him to enroll at the Institute of Banking Training in 2014.

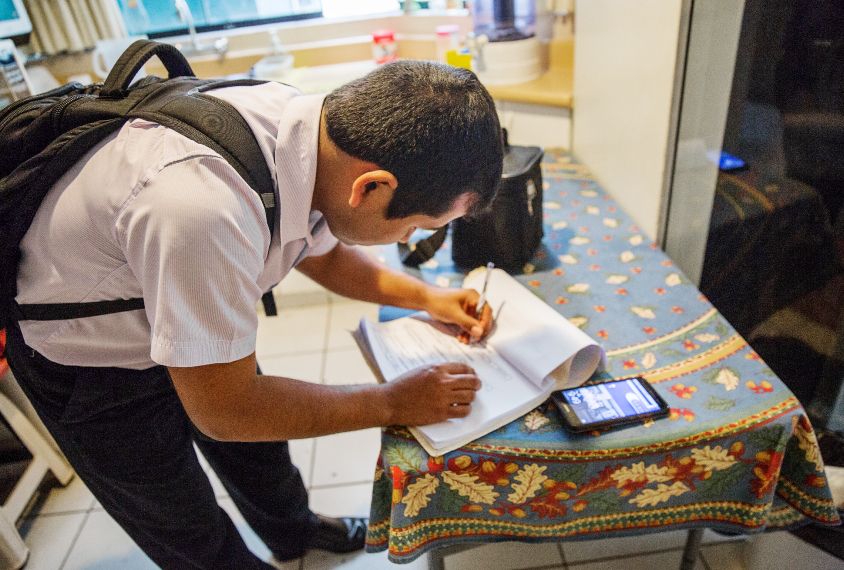

For three years, Pesantes studied or attended classes from 8 to 11 a.m. before heading to work. He returned to class from 6 to 10 p.m. and arrived home around midnight. After he graduated in October 2017, he completed an internship at CAP Asesores Empresariales, a consulting agency. And last week, he began his new job as an accountant at UNIMAQ, a rental store for construction equipment.

Pesantes is especially thrilled by the opportunity to pay for family vacations or take his family out to eat at a restaurant, according to his mother, Teresa Vera. Whenever she worries something might be too expensive, she says he tells her, “Don’t worry, when I make more money, we will be able to go on a longer trip.”

Mayo too takes great pride in how far Pesantes and López have come. “I remember how they were when they were little,” she says. “Now they’re an inspiration to others.”

Early start: Ronald Pesantes, 26, prepares breakfast at home before his long commute to work in Lima, Peru.

Helping hand: Pesantes, who has autism, says he is thrilled to be able to pay for vacations for his mother and the rest of his family.

Long road: Pesantes lives in the Villa María del Triunfo district, about two hours outside Lima.

En route: Pesantes’ two-hour commute to work begins with a taxi.

Transport trio: He also rides a subway, as well as a bus, to get to his job.

Data entry: He studied to be an accountant while holding a full-time job at a security firm.

Number cruncher: Pesantes’ hard work garnered him excellent grades and a job as an accountant.

Firm foundation: Sandro López, 37, helped finance the renovation of his family's home.

Devoted employee: Since 2001, López has worked as an office assistant at Alusud Peru, a company that produces plastic caps for food, drinks and other products.

Sound results: As part of his job, López, who is autistic, delivers earplugs to workers on the factory floor.

Model employee: Lopez has worked at the company for 17 years.

Job well done: López is the main breadwinner of his family, keeping them afloat during several crises. “I am glad about these achievements,” he says.

Recommended reading

Explore more from The Transmitter

Cracking the neural code for emotional states