Autistic people have historically performed poorly on a well-known test of theory of mind, or the ability to recognize and interpret other people’s desires, beliefs and intentions. Test-takers have to decide whether simple cartoons of at least two geometric shapes are moving across a computer screen randomly or in ways that mimic different types of social interaction, such as dancing with or surprising each other.

Scientists who use the test typically categorize the animations, developed by Uta Frith and Francesca Happé in 2000, as social or non-social and then assess participants’ abilities to match their labels. But as it turns out, even neurotypical people have different ideas about which of these abstract animations seem social, a new study finds, highlighting the influence of subjective experiences on the measure.

“Perception is highly subjective,” says lead investigator Emily Finn, assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. “This variability should be respected and taken seriously, both as an object of scientific inquiry and in our everyday lives.”

Previous research showed that people with autism were “sometimes less likely to declare an animation intended to be social as such,” Finn says. “Our research is arguing that we shouldn’t see things as so black and white — we can talk about responses as being more typical or less typical, but really, who is to say what is correct or incorrect with these animations?”

F

inn and her colleagues analyzed data from 1,049 neurotypical adults — 562 women and 486 men — who had had their brains scanned while they watched 10 Frith-Happé animations, each 20 seconds long. The data came from the Human Connectome Project, which mapped connections among different parts of the human brain.Five animations supposedly had social content, according to that project’s scientists, whereas five others did not. Participants nearly unanimously deemed some animations — such as one in which triangles move in straight lines like billiard balls — as non-social. But others — such as one involving an oblong-shaped fish and a circle that has a line reminiscent of a fishing pole — proved ambiguous, with the participants rating them as social, non-social or unclear.

“Two people seeing the same information — that is, an animation — may process that content differently, involving a large part of the brain, leading to totally different interpretations of it, some labeling it social and others non-social,” says study investigator Rekha Varrier, a postdoctoral researcher in Finn’s lab.

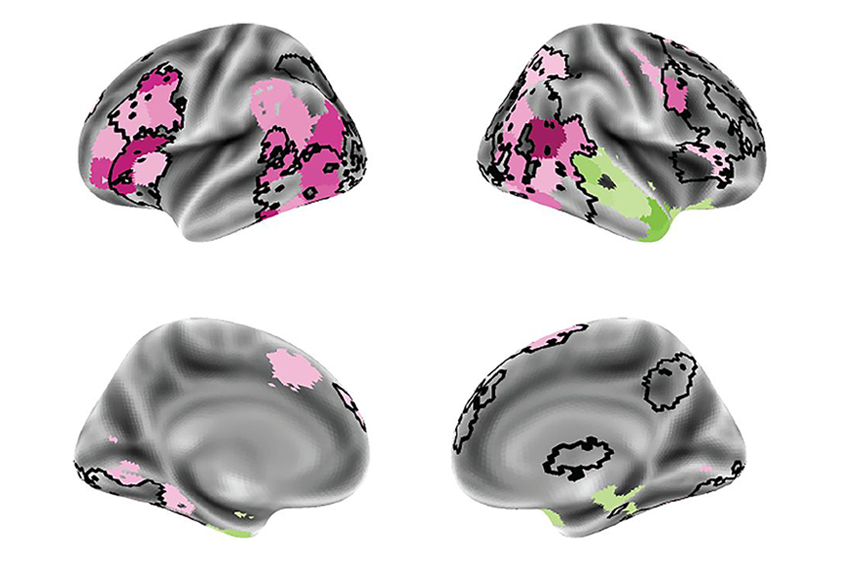

Many brain areas responded more strongly to content deemed social by the participants than to content they thought of as non-social, according to the functional magnetic resonance images. Perhaps unsurprisingly, increased activity in brain areas linked with social behavior, such as the occipital, temporal and prefrontal regions, more often coincided with animations the participants deemed social than with those the experimenters categorized as such.

“We were delighted to see data from such a large sample confirming our own small-scale studies showing rich mental state attribution to triangle animations,” says Happé, professor of cognitive neuroscience at King’s College London in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the study.

The research underscores how “we need to turn to large sample sizes to address inter-individual differences with sufficient statistical power,” says Carolin Mößnang-Sedlmayr, professor of clinical psychology and psychotherapy at SRH University Heidelberg in Germany, who did not take part in the work. Previous imaging studies of the subjective perceptions of animations may not have captured differences between neurotypical and autistic people because the groups were too small and variation within too subtle, she says.

F

urther analysis revealed brain regions — mostly in the temporal, occipital and subcortical areas — linked with gradations in social perception: The areas responded most when participants perceived cartoons as social, less when participants were unsure, and least when participants perceived them as non-social. “The brain is responsive not only to whether there is social information, but also how much social information there is,” Varrier says.High levels of internalizing traits — such as loneliness and anxiety — as reported on behavioral questionnaires, were associated with a slightly higher chance of perceiving the animations as social. These traits also tracked with reduced activity in the default mode network, which plays a role in self-reflection, as well as in brain regions linked to social perception. The scientists detailed their findings in the Journal of Neuroscience in December.

Prior work similarly found that internalizing traits correlated with having a greater sensitivity to social cues and the assigning of human qualities to inanimate objects. The new findings “might suggest we should routinely measure anxiety and depression when assessing social cognition,” Happé says.

All in all, the findings are “surely an important step in defining a complex network critical for social perception and cognition,” says Ralph-Axel Müller, professor emeritus of psychology at San Diego State University in California, who was not involved in the work.

The participants were generally slightly biased toward perceiving animations as social — a tendency that evolution may have favored, the researchers suggest, because mistakenly thinking someone is trying to interact with you is likely less costly than missing out on potentially vital social cues.

“It would be interesting to know if there is a social perceptual bias associated also in the autistic population,” says Frith, emeritus professor of cognitive development at University College London. And because “there is a mystery as to when in evolution the ability to detect intentional behavior, as opposed to goal-directed behavior, first appeared,” she adds, researchers should also try to adapt this type of task for use with animals.

The scientists next want to isolate specific visual features, such as the speed of each shape or their velocities relative to each other, that cause people to perceive social interactions in these animations, Finn says. Such research could help detect individual differences between subsets of people with autism and relate them with their history and traits, Frith says.

“Our hypothesis is that individuals vary in the specific doses of each feature they need to see in order to declare the presence and nature of a social interaction,” Finn says.