People with milder forms of autism struggle as adults

Contrary to popular assumption, people diagnosed with so-called mild forms of autism don’t fare any better in life than those with severe forms of the disorder. That’s the conclusion of a new study that suggests that even individuals with normal intelligence and language abilities struggle to fit into society because of their social and communication problems.

Contrary to popular assumption, people diagnosed with so-called mild forms of autism don’t fare any better in life than those with severe forms of the disorder. That’s the conclusion of a new study that suggests that even individuals with normal intelligence and language abilities struggle to fit into society because of their social and communication problems.

In fact, people diagnosed with pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) are no more likely to marry or have a job than those with more disabling forms of autism, according to a Norwegian study published online in June in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders1.

Early intervention has the potential to alter this trajectory, say experts. But until today’s children with autism reach maturity, it will be hard to say how much behavioral intervention at a young age can alter the course of their lives.

“The implication of our findings is that the consequences of having an autism spectrum disorder with profound difficulties in communication skills and social impairment can’t be compensated for by either high intellectual level or normal language function,” says lead investigator Anne Myhre, associate professor of mental health and addiction at the University of Oslo in Norway.

These findings provide support for the proposed merging of pervasive developmental disorder into the autism spectrum in the DSM-5, the edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) set to be published in 2013, the researchers say.

The new edition of the manual takes a spectrum approach, absorbing the separate categories of childhood disintegrative disorder, Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS into the broad category of autism spectrum disorder. The draft guidelines note that symptoms must appear in early childhood and affect everyday functioning.

“I’m glad that the authors see this as support for the DSM-5 proposed definitions,” says Sally Rogers, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis’ MIND Institute. Rogers is a member of the neurodevelopmental working group revising the diagnostic criteria for autism.

Single and disabled:

Myhre’s team investigated marital status, mortality and criminal records, and disability pension awards for 113 individuals who would meet contemporary criteria for autism. Of that number, 39 fall into the PDD-NOS category. More than half the participants — including 23 of the 39 with PDD-NOS — have an intelligence quotient (IQ) of 70 or less.

All were treated in the children’s unit at the National Centre for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in Oslo, Norway, between 1968 and 1988. The researchers tracked these participants using government-issued identification numbers.

They found that by age 22, 96 percent of the group had been awarded a disability pension from the government. Nearly all were unmarried — 99 percent of those with autistic disorder, compared with 92 percent of those with PDD-NOS. The crime rate for the group as a whole was little more than half that of the general population, although more individuals with PDD-NOS than autism had been convicted of a crime.

The study’s comparatively bleak findings are a surprise, say experts.

“The PDD-NOS group is generally better functioning, at least in childhood, so we would expect them to do better as adults,” says Sigmund Eldevik, associate professor of behavioral science at the Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, who was not involved with the study.

In July, Eldevik reported that young children with autism who receive behavioral interventions in preschool have higher IQs and adaptive behavior scores than those who do not receive the intervention2.

However, the individuals in Myhre’s study grew up during a time when autism was typically diagnosed later in childhood, and there were few early intervention programs.

For example, autism was not classified as separate from schizophrenia until the release of the third edition of the DSM in 1980. And Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS were not included until the DSM-IV’s release in 1994.

To address the diagnostic changes, the researchers used detailed descriptions of symptoms, psychological test results, school performance and other records to retroactively diagnose autism or PDD-NOS in the study participants according to DSM-IV criteria.

Eldevik says the changes in DSM subcategories would probably not affect the study’s findings, however, as clinicians in Norway generally use the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

“The PDD-NOS diagnosis from DSM-IV is very similar to the ‘Atypical Autism’ diagnosis from ICD-10, which we are using in Norway,” he says.

What’s more, other studies of individuals with PDD-NOS have turned up similar results. A 2009 European study reported that few individuals with PDD-NOS, autism or Asperger syndrome live independently3. That study found that antisocial personality disorder and substance abuse are more common in the PDD-NOS group, together with the mood and anxiety disorders shared by all the subgroups. Although all 122 people in the study have normal IQs, only 40 percent were employed at the time of the study, and 84 percent had never been in a long-term relationship.

Limited opportunities:

Relatively few long-term studies report on individuals with PDD-NOS but, in general, research on social and employment prospects for people on the autism spectrum are not encouraging.

For example, a study published earlier this year found that in the U.S., young adults on the spectrum who do not have an intellectual disability are in some ways worse off than those who do, as there are fewer programs to support their needs. They are at least three times more likely to have no structured daytime activities, for example4. Another study by some of the same researchers showed that 70 adults with Down syndrome enjoy higher levels of independence, more social opportunities and receive more services compared with 70 adults who have autism5.

This picture of limited opportunity for social engagement and growing isolation in adulthood for those on the spectrum is replicated by a study in April, which showed that more than half of young adults with autism had not gotten together with friends in the previous year6. Another study in February found that close to 40 percent of young adults with autism in the U.S. receive no services whatsoever after high school graduation.

In Norway, people on the spectrum are eligible for a government disability pension at age 18. Although only 5 percent of the Norwegian population as a whole receives this pension, 89 percent of individuals with autism in the new study receive it, as do 72 percent of the PDD-NOS group.

The higher level of intellectual disability in the autism group may explain the lower levels of disability awards in the PDD-NOS group, says Rogers. “This suggests that interventions that increase intellectual abilities will lead to better outcomes,” she says. Although most studies suggest that those with higher IQs don’t necessarily fare better in life, those individuals did not benefit from the kind of targeted early interventions now available, which address both intellectual and social functioning, she says.

High-quality early intervention is the only treatment that has shown improvement in intellectual functioning in people with the disorder, Rogers says. As more individuals with the disorder are diagnosed and receive treatment early on, future generations may face better outcomes.

Early intervention is already leading to markedly better intellectual functioning in children with autism, says Amy Wetherby, professor of communication science and disorders at Florida State University.

“The whole landscape of autism is changing because we are better at identifying the cognitively higher-functioning individuals,” she says. “With good early intervention, most end up within normal limits [on intelligence tests].”

References:

1: Mordre M. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2011) PubMed

2: Eldevik S. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2011) PubMed

3: Hofvander B. et al. BMC Psychiatry 9, 35 (2009) PubMed

4: Taylor J.L. and M.M. Seltzer J. Autism Dev. Disord. 41, 566-574 (2011) PubMed

5: Esbensen A.J. et al. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 115, 277-290 (2010) PubMed

6: Liptak G.S. et al. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. Epub ahead of print (2011) PubMed

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

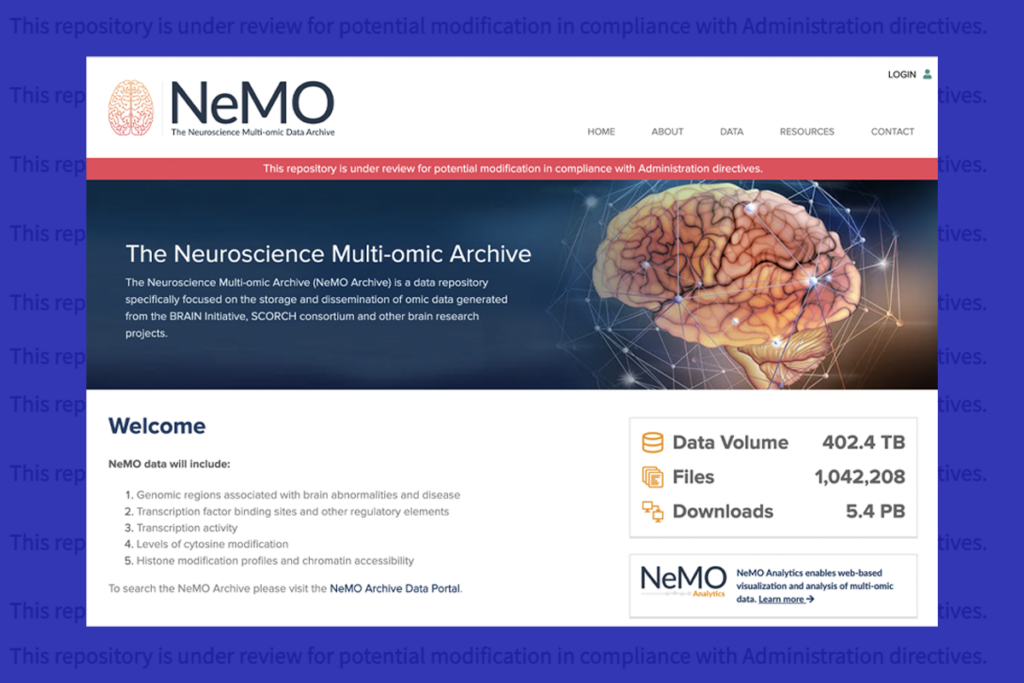

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors