People with autism misjudge quality of visual signals

Adolescents with autism can gauge the direction of moving objects just as well as healthy controls can, but their confidence in their visual ability is sometimes misplaced, according to unpublished data presented yesterday at the IMFAR 2010 conference in Philadelphia.

Adolescents with autism can gauge the direction of moving objects just as well as healthy controls can, but their confidence in their visual ability is sometimes misplaced, according to unpublished data presented yesterday at the IMFAR 2010 conference in Philadelphia.

The results suggest that people with autism have trouble not with perceiving motion, but with using that information to make decisions, the researchers say.

Studies of motion perception often use animated dots, some fraction of which are moving in the same direction. Healthy people can pick out this so-called ‘coherent motion’ when about 10 percent of the dots move in the same direction. Previous work suggested that people with autism need about three times as many dots to see the ‘hidden’ movement.

Richard Krauzlis and colleagues at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, used the same test, but with a twist.

In the previous version of the task, the participants set the pace of the test. They watch the animation and when they are ready, move their eyes to either the left or the right to indicate the direction of the mass of dots. Krauzlis instead had participants wait about one second after watching the animation before they made their choice. With this tweak, participants with autism performed just as accurately as controls did — suggesting that they have no defect in basic visual perception.

To clarify this aspect, the researchers added another element to the test. They asked nine participants with autism and eight controls to make a wager — high or low — on whether the direction they chose was correct. After each trial, they gave the participants a monetary reward for good bets.

Healthy participants based their wagers on the task’s difficulty, betting low on trials in which only a few dots moved in concert. But the autism group almost always made the higher bet. “Even when motion coherence was at zero, they still bet high,” Krauzlis says.

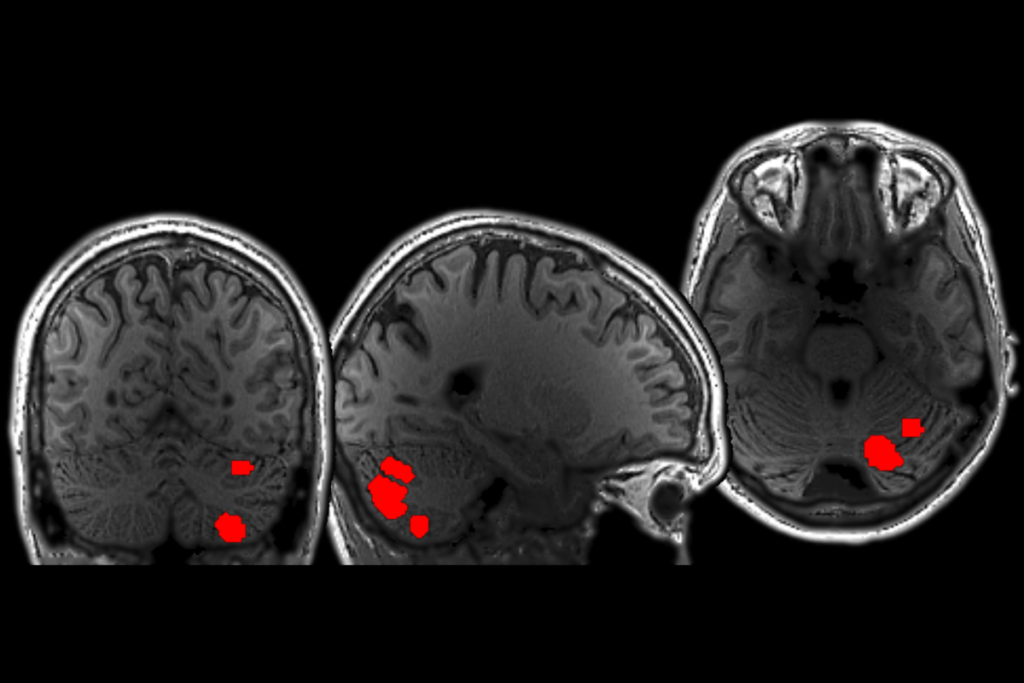

This goes against the hypothesis that autism arises from a problem in the brain’s basic visual circuits, he says. Instead, he suggests that the trouble lies in their ability to understand the quality of visual information.

“The sensory signals themselves seem more or less intact,” Krauzlis says. “But the interaction of sensory signals and the process of decision-making is not normal.”

See all reports from IMFAR 2010.

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

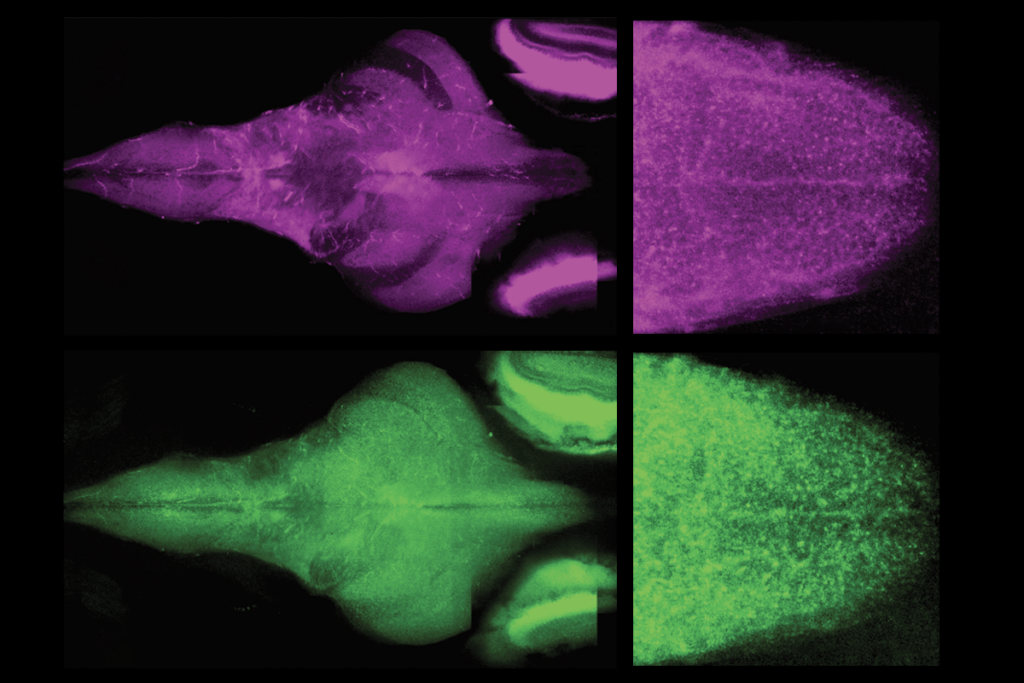

Cerebellum responds to language like cortical areas

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles