Few people mourn Asperger syndrome’s loss from diagnostic manuals

Our concept of autism has evolved over the past 20 years, rendering redundant the diagnostic labels of Asperger syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified.

In just a few months, the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) is set to eliminate two diagnostic categories related to autism: ‘Asperger’s syndrome’ and ‘pervasive developmental disorder, unspecified,’ currently listed as subtypes of autism, will be subsumed into the single definition of ‘autism spectrum disorder.’

The ICD-11 is following the path set in 2013 by the DSM-5, the then-new version of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.”

I favor this consolidation.

Asperger syndrome entered the U.S. diagnostic system with the publication of the DSM-IV in 1994. Even then, researchers questioned its validity, suggesting it might be just another variant of autism1. They also perceptively discussed the introduction of the ‘remainder category,’ pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and warned that “unless it is clearly formulated, there is a danger that it will cease to have any useful meaning.”

The ICD-10, the version of the ICD currently in use, similarly stated that Asperger’s syndrome is a diagnosis of “uncertain nosological validity.”

So these diagnoses were always controversial. But over the past 5 to 10 years, our changing definition of the term ‘autism,’ and the consequent changes in how we go about clinical ascertainment, have rendered redundant the need for separate diagnoses of Asperger syndrome and PDD-NOS.

Distinctions lost:

In both the ICD-10 and DSM-IV, the diagnostic criteria for an ‘autistic disorder’ required evidence of delays or abnormal functioning before the age of 3 years in social communication (language), social interaction, or symbolic or imaginative play. The alternative diagnosis of ‘Asperger’s disorder’ (DSM-IV-TR) was determined by the absence of significant cognitive or language delay, although the definition did allow for the presence of abnormal social interaction during that early developmental period.

So, in practice, the distinction between an autistic disorder and Asperger’s disorder usually came down to a decision about whether or not there had been generalized developmental delay, or language delay within the first 3 years. By extension, the clinical diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder in older children and adults often rested on whether the individual with features of autism had an intelligence quotient in the normal range and good formal language skills, even though these were never explicit diagnostic criteria.

In the early 1990s, clinicians firmly believed that at least three-quarters of individuals with autism had ‘mental retardation’ (now termed ‘intellectual disability’).

But we now know that most individuals with autism possess average verbal and nonverbal intelligence. The prevalence of associated intellectual disability has been falling, such that more than two-thirds of newly diagnosed individuals have intelligence quotients in the normal range, according to recent U.S. national surveys2. The great majority of children with autism in the United Kingdom are in mainstream classrooms.

The DSM-5 and ICD-11 do not require a history of early cognitive or language delay as essential components of autism spectrum disorder. As a result, Asperger syndrome is satisfactorily subsumed under the new rubric.

Language labels:

Using the DSM-IV, clinicians usually applied a diagnosis of PDD-NOS to individuals with social-communication impairments who lacked the cognitive rigidity and stereotypies essential for an autism diagnosis3.

We suspect these individuals now receive a diagnosis of social (pragmatic) communication disorder, a new diagnostic category in the DSM-5. This condition encompasses a constellation of language features that are subsumed under ‘developmental language disorder (with impairment of pragmatic language)’ in the ICD-114.

These language diagnoses now essentially replace PDD-NOS and, in the ICD-10, ‘pervasive developmental disorder, unspecified.’

In a live debate for Spectrum about the merits of our evolving diagnostic classification of autism spectrum disorders, none of the speakers — myself included — mourned the loss of Asperger syndrome or PDD-NOS from the DSM-5. (The arguments were scientific, and not related to the character of Hans Asperger.) But clinicians and researchers will continue to argue about the threshold of clinical significance for this multidimensional, complex condition.

David Skuse is professor of behavioral and brain sciences at University College London and deputy director of the Population, Policy and Practice program at the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health.

References:

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

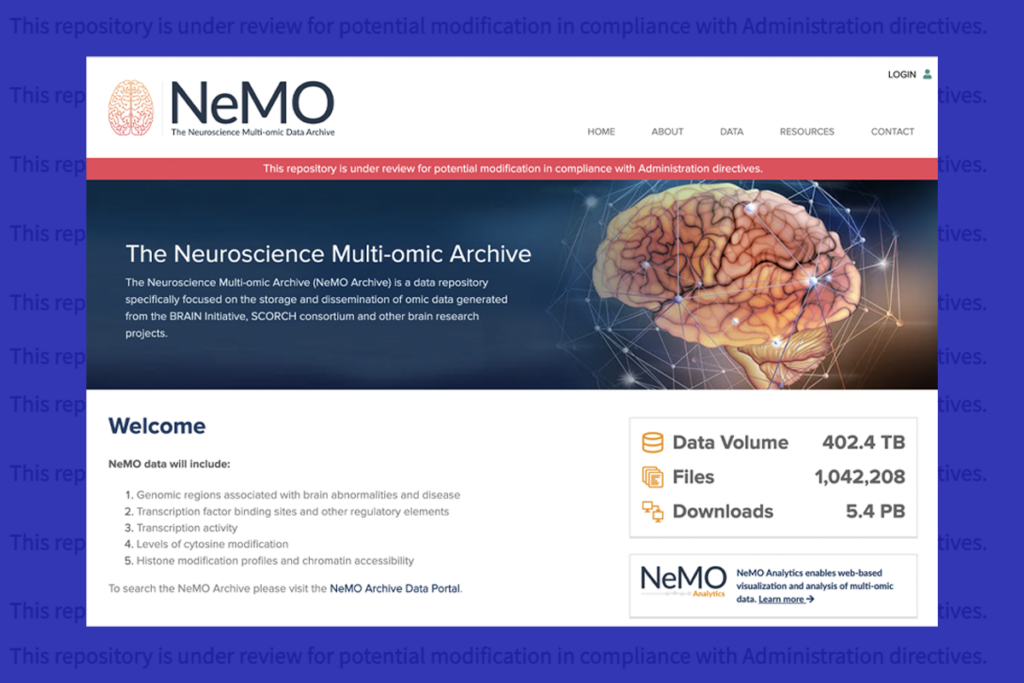

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors