Parents’ DNA tags tied to autism symptoms in toddlers

Women who have unusual patterns of chemical tags on their DNA during pregnancy may give birth to children who develop autism symptoms. The preliminary results are being presented today at the 2015 International Meeting for Autism Research in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Women who have unusual patterns of chemical tags on their DNA during pregnancy may give birth to children who develop autism symptoms. The preliminary results are being presented today at the 2015 International Meeting for Autism Research in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Chemical tags such as methyl groups can turn genes on or off and may appear in response to environmental triggers.

“We think that these tags are giving us a glimpse of the genetic and environmental factors in parents that may contribute to risk for autism in their children,” says lead researcher Daniele Fallin, director of the Wendy Klag Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

The findings come on the heels of a similar study of men by the same research team. That study, published last month in the International Journal of Epidemiology, found that fathers of children with autism symptoms show unusual patterns of methylation in their sperm1.

Together, the studies suggest that alterations in methylation in parents are associated with autism in their children. But no one knows exactly why some configurations of these tags might lead to the disorder.

“These findings are intriguing, but more work needs to be done to understand how to make sense of them,” says Jay Gingrich, Sackler Institute Professor of Clinical Developmental Psychobiology at Columbia University, who was not involved in either study.

EARLI influences:

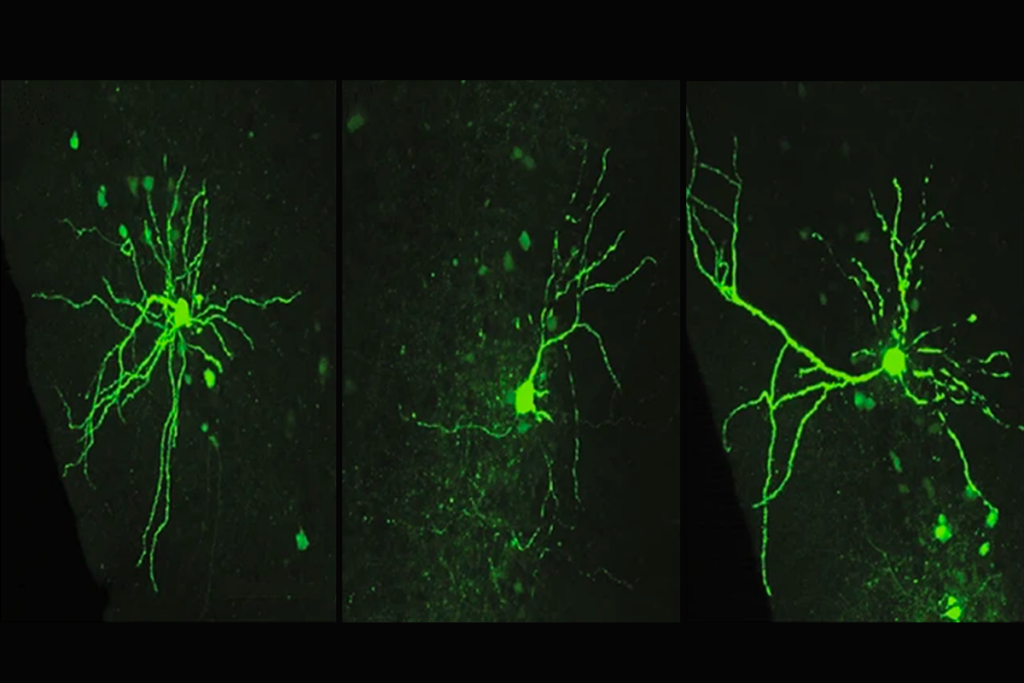

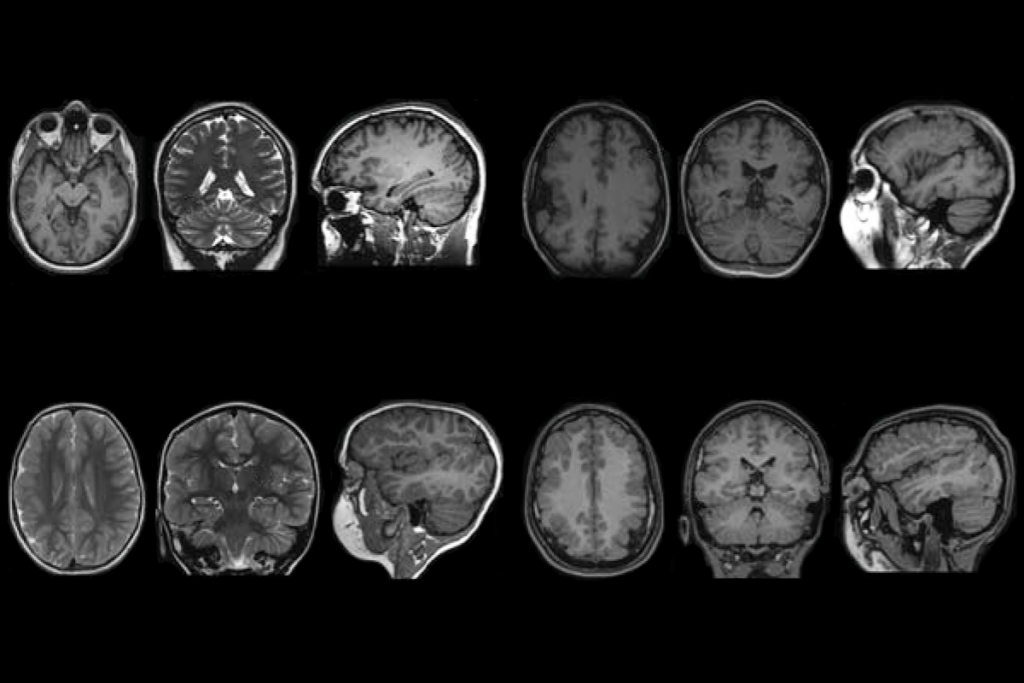

Several studies have implicated altered methylation in autism. A 2014 investigation uncovered unusual arrangements of methyl groups in postmortem brains of people with autism2. A second study published the same year looked at identical twin pairs in which only one twin has autism, and found differences in these chemical patterns between twins3.

The new studies are part of a long-term project, launched in 2009, called the Early Autism Risk Longitudinal Investigation (EARLI). This project follows parents of children with autism through subsequent pregnancies. These so-called ‘baby sibs’ are about 20 times more likely than average to be diagnosed with autism.

Fallin and her colleagues examined DNA methylation patterns in the blood of 79 pregnant women enrolled in EARLI. The researchers also collected blood and semen from 44 fathers while their female partners were pregnant. They looked at 7 million sites in the genome called CpGs that are likely to be marked by a methyl group.

When the children were about 1 year old, the researchers looked for signs of autism using the Autism Observation Scale for Infants. Higher scores on this test indicate more severe symptoms of autism.

So far, the team has found that in women whose children scored in the severe range of symptoms, a short stretch of chromosome 6 bears an unusually large number of methyl groups. “We think this shows that there is an association between methylation at this spot in the mothers’ blood during pregnancy and the performance of their children 12 months later,” Fallin said at a press conference yesterday.

The researchers have also identified 193 regions in sperm where unusually high or low numbers of methyl groups track with autism symptoms in children. Some of these regions reside in genes that aid neuron formation or other aspects of brain development.

Although the findings are preliminary, they point to new directions for research, such as exploring how the aberrant methylation in parents affects gene expression, says Yong-Hui Jiang, associate professor of medical genetics at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, who was not involved in the studies.

Future studies should include control groups for comparison, Jiang says. They could also address whether the unusual configurations of these chemical tags in parents reappear in their children. “If they do, that builds confidence that it’s a meaningful, functional difference,” he says.

For more reports from the 2015 International Meeting for Autism Research, please click here.

References:

1. Feinberg J.I. et al. Int. J. Epidemiol. Epub ahead of print (2015) PubMed

2. Ladd-Acosta C. et al. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 862-871 (2014) PubMed

3. Wong C.C. et al. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 495-503 (2014) PubMed

Recommended reading

Assembloids illuminate circuit-level changes linked to autism, neurodevelopment

Impaired molecular ‘chaperone’ accompanies multiple brain changes, conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Rajesh Rao reflects on predictive brains, neural interfaces and the future of human intelligence