Parade of mice with top autism mutation puzzles scientists

Mice missing one copy of a top autism gene show many of the features seen in people with the mutation — but not social deficits.

Mice missing one copy of a top autism gene show many of the features seen in people with the mutation — but not social deficits.

With two new models described at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego, there are now four sets of mice that each lack a copy of the gene, CHD8. This embarrassment of riches stems from the fact that, in the past few years, CHD8 has emerged as a leading candidate for autism risk.

So far, the mouse models all recapitulate different sets of features seen in people. For example, nearly all people with a rare mutation in one copy of the gene have autism, along with a large head and wide-set eyes. The researchers who presented one of the new models yesterday are the first to report that their mice also have wide-set eyes. Neither of the models presented at the meeting show any signs of social deficits reminiscent of autism. (Two other published models of CHD8 do report some social deficits.)

Looking at the effect of CHD8 mutations in mice can help researchers understand the molecular underpinnings of autism, says Philipp Suetterlin, a postdoctoral associate in Albert Basson’s lab at King’s College London, who presented the findings yesterday.

In their study, Suetterlin and his colleagues blocked the expression of one of two copies of CHD8 in mice. Brain volume in these mice is about 3 percent larger than in controls. The distance between their eyes is also greater than in controls.

Expression effect:

CHD8 codes for a protein that controls gene expression by changing the structure of chromatin, the complex of protein and DNA. Loss of one copy of CHD8 in cultured cells alters the expression of hundreds of genes, including many autism candidates.

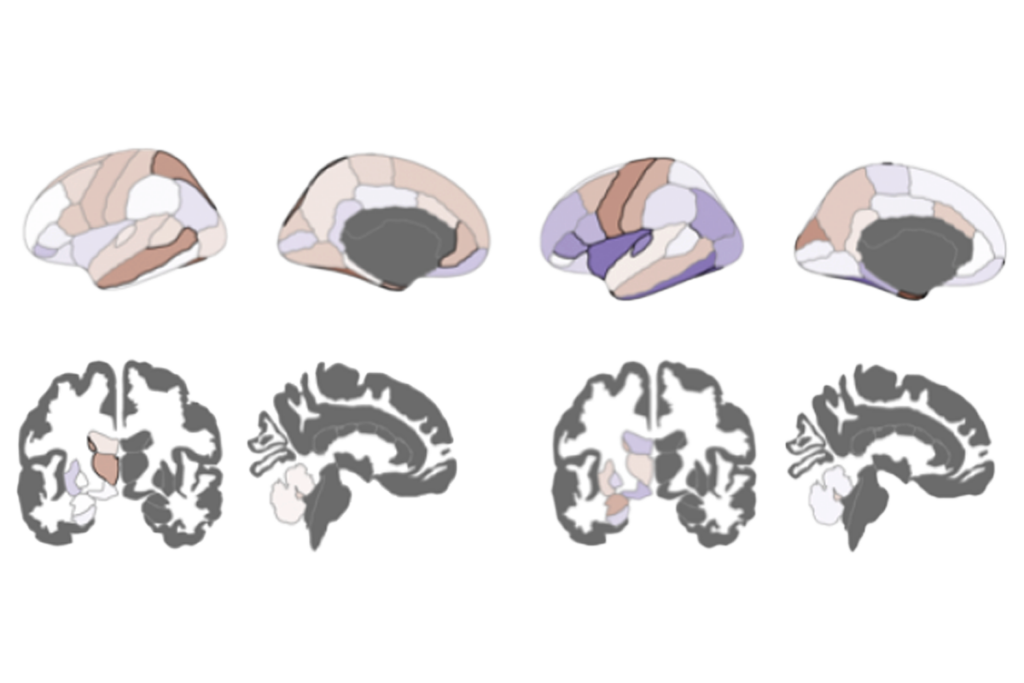

In the new mice, however, the loss of a CHD8 copy boosts the expression of nine genes and dampens that of five. When the researchers dropped CHD8 expression by roughly 60 percent rather than 50, the mice show altered expression of more than 2,000 genes. And their brains are 5 percent larger than those of controls, with effects across many regions, including the cingulate cortex, the hippocampus and the cerebellum.

The researchers haven’t yet looked at the exact levels of CHD8 protein in these mice or in people. Still, the study suggests that mice are more tolerant of certain mutations than people are. “The findings suggest there is a threshold for expression somewhere between 40 and 50 percent that needs to be crossed in mice,” Suetterlin says.

The model does not show signs of the social or repetitive behavior seen in autism. Pups vocalize normally to their parents, and adult mice show a preference for a mouse over an object.

Social rodents:

The second new model, described today at the meeting, also does not show signs of social deficits or repetitive behaviors. The researchers first reported results from these mice in May at the International Meeting for Autism Research.

The mice have enlarged brains and altered expression of hundreds of genes, including many autism candidates, such as ANK2.

Preliminary data indicate that these mice show roughly 50 percent the normal level of CHD8 expression, but their protein levels may be even lower, says Andrea Gompers, a postdoctoral associate in Alex Nord’s lab at the University of California, Davis.

It’s encouraging that both new models do not show social deficits, says Jill Silverman, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis. Silverman characterized behavior in the second new CHD8 model but was not involved in the first.

“We’ve seen a lot of things that fully corroborate one another, and the few things that we didn’t, there are reasons that are easily identified,” she says. “Overall, the two models together are really powerful.”

A study published in September reported that one of the older sets of CHD8 mice is less social than controls are1. Those mice also show signs of rigid thinking, which is reminiscent of the repetitive behaviors seen in people with autism.

In the meantime, at least two more research teams are generating mice with CHD8 mutations.

For more reports from the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

References:

- Katayama Y. et al. Nature 537, 675-679 (2016) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils phenotypic signatures of multiple neurodevelopmental conditions

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Altered excitatory circuits in CHD8-deficient mice; and more