Editor’s Note

This article was originally published 13 January 2021 as a conference report from the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome meeting. The results have since been published in Neuron.

Infusions of the hormone oxytocin may make mice that model autism more social by normalizing their brain activity patterns.

This article was originally published 13 January 2021 as a conference report from the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome meeting. The results have since been published in Neuron.

Infusions of the hormone oxytocin make mice that model autism more social by normalizing brain activity patterns. Researchers presented the findings virtually yesterday at the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome. (Links to abstracts may work only for registered conference attendees.)

The mice lack a gene called CNTNAP2, which, when mutated in people, is associated with autism, language impairments and altered brain connectivity. The animals also have unusually few oxytocin-producing neurons and show little interest in mingling with other mice.

“[They] don’t spend a lot of time interacting with a new partner, and when you give oxytocin it more than doubles the interaction time,” says lead investigator Katrina Choe, assistant professor of psychology, neuroscience and behavior at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

In the new work, Choe and her colleagues captured snapshots of brain activity in mice after injecting them with oxytocin. The injection does not affect brain activity in control mice, the researchers found. But in mice missing CNTNAP2, it activates several brain regions that oxytocin-producing neurons normally plug into, including a reward-associated region called the nucleus accumbens.

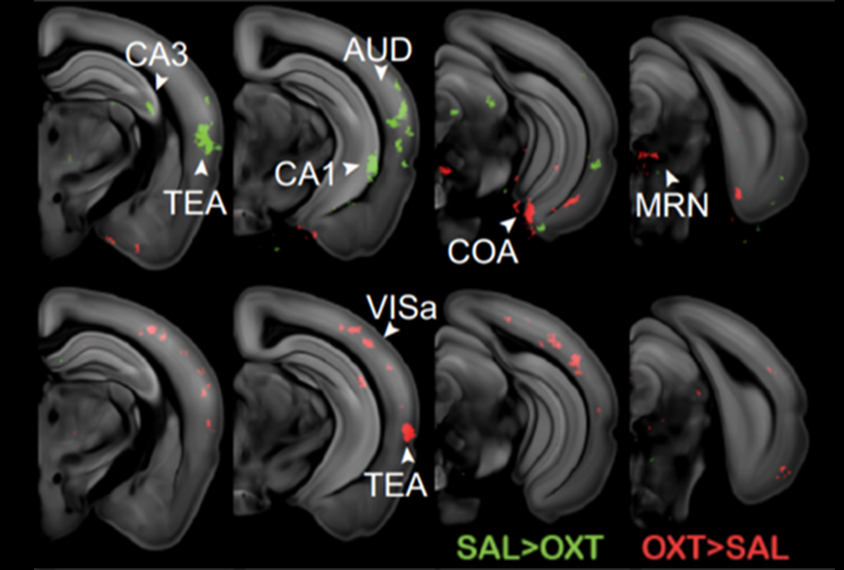

The researchers then imaged the brains of the mice at rest to compare the degree of connectivity within brain regions related to social behavior and between social regions and other brain areas.

In CNTNAP2 mice, connections across social brain areas are weaker than in control mice, but connections between social regions are unusually strong. But an oxytocin injection normalizes this pattern, boosting the tie among social brain areas and reducing it elsewhere. In particular, oxytocin strengthens the connections between three distinct pairs of brain regions, one of which involves the medial prefrontal cortex and another the nucleus accumbens.

“We identified several interesting circuits and connections that could be underlying oxytocin’s effects on social behavior,” Choe says.

To see how oxytocin affects brain activity when it is produced internally rather than injected, the researchers selectively stimulated oxytocin-secreting neurons in the hypothalamus. These switched-on oxytocin neurons activated the nucleus accumbens most strongly, the team found.

Finally, the researchers used a technique called optogenetics to selectively switch on and off oxytocin secretion only into the nucleus accumbens. When oxytocin flows into the region, CNTNAP2 mice enthusiastically interact with another mouse, the team found, but when that flow is staunched, the mice return to their solitary ways. Neither manipulation affects control mice.

“We have collected many pieces of converging evidence that suggests that the nucleus accumbens could be a key region” for modulating social behavior via oxytocin, Choe says.

Read more reports from the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome.