Owen’s odyssey: The difficult path to an autism diagnosis

This is part 1 of the story of one boy’s long journey to an autism diagnosis and therapy. Part 2 will track Owen’s progress later this year.

I

t’s before sunrise on a Monday morning in late September, and Danyel Couture opens a white bedroom door. Light from the hallway beams onto the small face of her 3-year-old: Owen.Owen’s eyelids flutter open and shut a few times. Couture tiptoes across the plush white carpet toward his bed and switches on a small dinosaur-shaped lamp. “Wakey, wakey,” she whispers. “How’d you sleep?” She kneels down to stroke Owen’s arm and kiss his head.

Owen slowly rolls onto his back and kicks off the blanket. The excavator on his pajama shirt matches a yellow stuffed toy at the side of his bed. Couture picks up a small white bear, his near-constant companion. She squeezes ‘Bearsie Wearsie’ and places it next to Owen’s pillow, where it begins to vibrate and play a soft lullaby.

“You ready to get up?” she prods. “We have such a big day ahead of us. It’s going to be so awesome.”

Today is Owen’s first day of “school” — and it has come earlier for him than for many children. Owen was diagnosed with autism in May. His doctors recommended he start intensive behavioral therapy as soon as possible, which prompted his parents to look for a facility that provides it.

This day is also the culmination of a long and arduous struggle for the family. For more than two years, Couture could not get any doctors or therapists to take her concerns about Owen’s lack of social interest or his delayed crawling, walking or language seriously. After his diagnosis, the family’s health insurance company twice declined to cover the cost of autism therapy for Owen. And it was only a week ago, after months of waiting for the insurance to come through, that Owen was given permission to start at the Prism Autism Center in Farmington, Connecticut, a school-like medical facility about a 30-minute drive from the family’s home.

The family’s experience is hardly unique: Early diagnosis and intervention can lead to a better outcome for autistic children, and yet many families struggle with long delays. “It’s just such a common course of events,” says Lisa Shulman, a developmental pediatrician who specializes in autism. Because of problems with screening tests for autism, a lack of training for pediatricians and limited access to experts for families, the average age of diagnosis in the United States is 4 years, even though the signs of autism are usually evident much earlier.

The long wait times can make an already fraught process much more stressful. “I’m so nervous about today,” Couture says. “I’m not sure how it’s going to go.”

She and her husband, Christian, have been preparing Owen over the past week, talking with him about what to expect at Prism. Owen often becomes distressed when his mother leaves the room. And since he was 6 months old, he has spent most weekdays at the same local daycare center. Any changes to his routine might throw him off kilter.

“Do you want to wear the new outfit we got yesterday, or do you want to wear something else?” Couture asks Owen as he crawls out of his bed, clutching a small white blanket.

“Something else,” Owen says, draping the blanket over his head.

She coaxes him out from under the blanket and dresses him in navy shorts and a plaid blue-and-white collared shirt that Owen picked out. “What do we do every morning?” she prompts. “Brush your teeth, do your hair?”

“Your hair,” Owen echoes. The two head down the hall to the bathroom. A few minutes later, they go downstairs. Owen plops down to eat a pastry in a large chair in the living room, where his father is watching a bit of the morning news before work.

“Owen, you’ve got to get ready,” Couture says. “Give Daddy big hugs and kisses.” Owen hops down from his chair and embraces his father.

“Bye, have fun at big-boy school,” Christian Couture says.

6:37 a.m.

O

wen opens the garage door using a small black remote, climbs into the back seat of the family’s white Volkswagen SUV and buckles himself into his car seat. “I’ve got this garage opener,” he says several times.His mother backs the car out of the driveway onto a quaint, tree-lined street. As she drives, she begins to reminisce about Owen as a baby. He was just 6 months old when she saw the first hints of autism, she says. Owen didn’t like to be held while he was being fed, and he typically preferred to lie by himself in a rocker or on the floor. “I always knew something was up, but no one believed me,” she says.

By the time Owen was 10 months old and still wasn’t turning over or sitting up on his own, the Coutures enrolled him in the state’s ‘Birth to Three’ program, for children with delayed development. A physical therapist spent a year working with Owen, helping him develop his lagging motor skills. The therapist reassured his parents that he had no red flags for autism.

But to Couture, the signs only became clearer. When Owen was 2, he began to focus intently on the wheels on his toy cars, she says, and liked to play with unusual items, such as light switches and the garage-door opener. “That’s really what tipped me [off]; how he plays is so different,” she says. Still, the pediatrician told her not to worry — especially after Owen passed his 18- and 24-month standardized autism screens with flying colors.

Autism screens are notoriously unreliable. One of the most popular, the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, misses most children with autism, according to a study published earlier this year. And even when children need further evaluation, most are not referred to a specialist. Some pediatricians say they lack the training or resources they need to properly screen children for autism. Others say they don’t want to worry parents and so deliberately take a wait-and-see approach. Owen’s pediatrician was among the latter.

“Pediatricians are in a very difficult situation because, first of all, they don’t have a lot of time; they don’t have a lot of training in what are the signs [of autism] specifically,” says Catherine Lord, distinguished professor of psychiatry and education at the University of California, Los Angeles. “We need more guidance for pediatricians on what to do,” she says: “How do you use what the parents are telling you in a better way?”

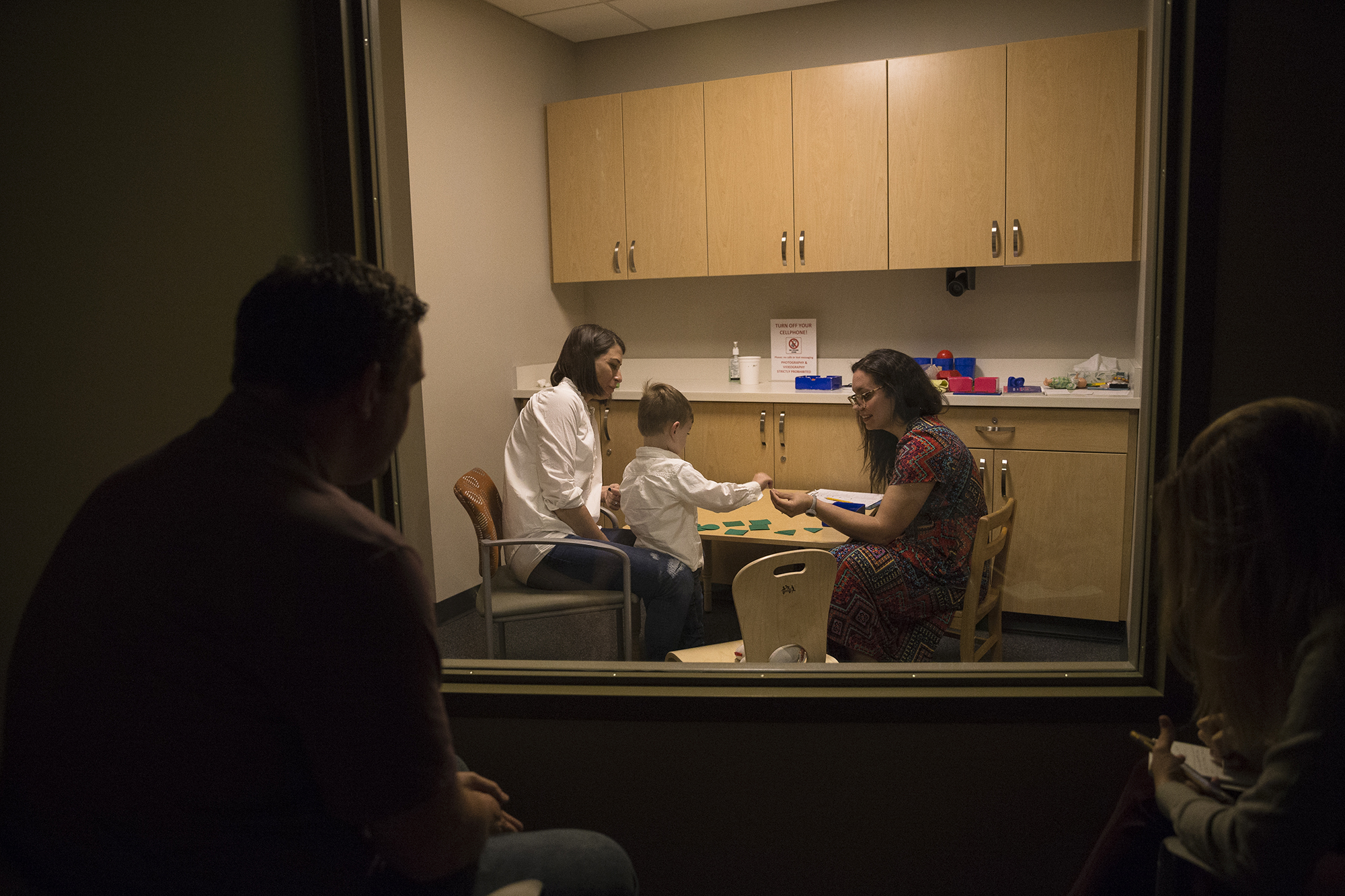

Test time: Owen greets a staff member at the Yale Child Study Center during his autism evaluation in May.

Holding pattern: Owen receives a kiss from ‘Bearsie Wearsie.’

Letter grade: Part of the evaluation assesses Owen’s grasp of language.

Moving parts: Owen threads beads on a string to demonstrate his fine-motor skills.

Quiet time: Owen takes a break with his father so the testing doesn’t tire him out.

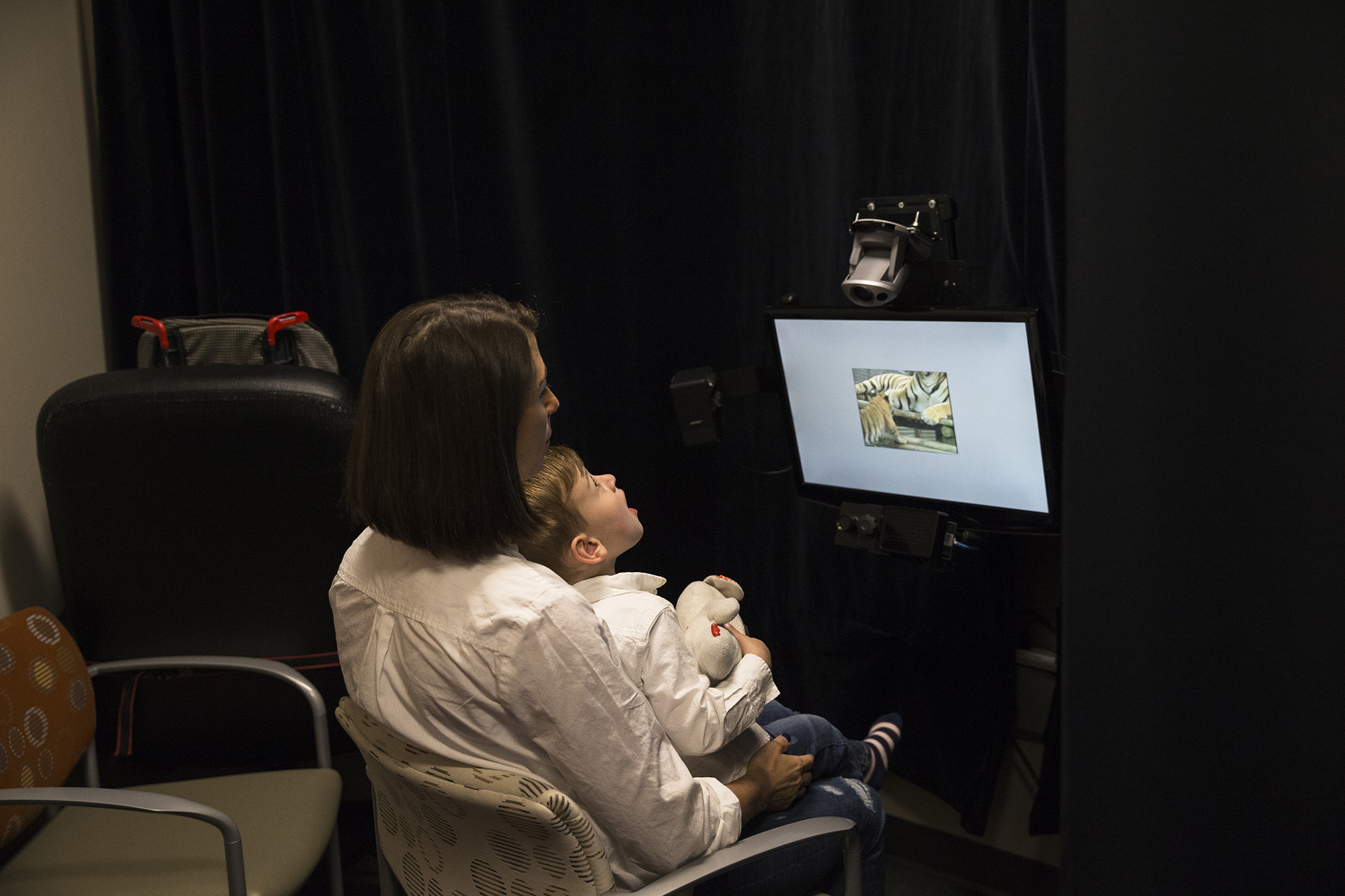

Cat tracks: As Owen watches a video of a baby tiger, an eye-tracking device monitors his gaze.

Shape shifter: A clinician evaluates Owen’s ability to follow instructions.

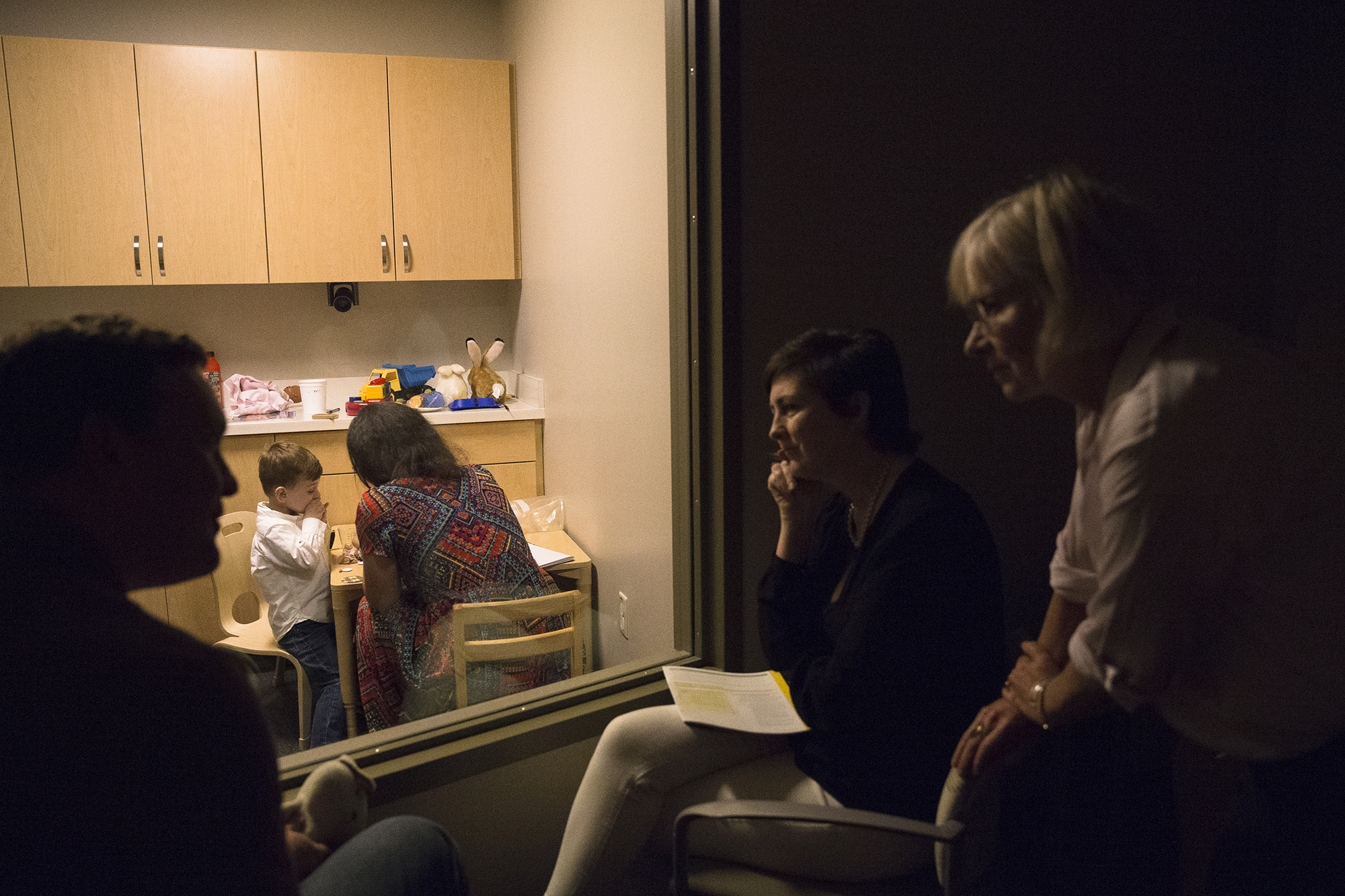

Expert input: Clinicians discuss their observations of Owen with his father.

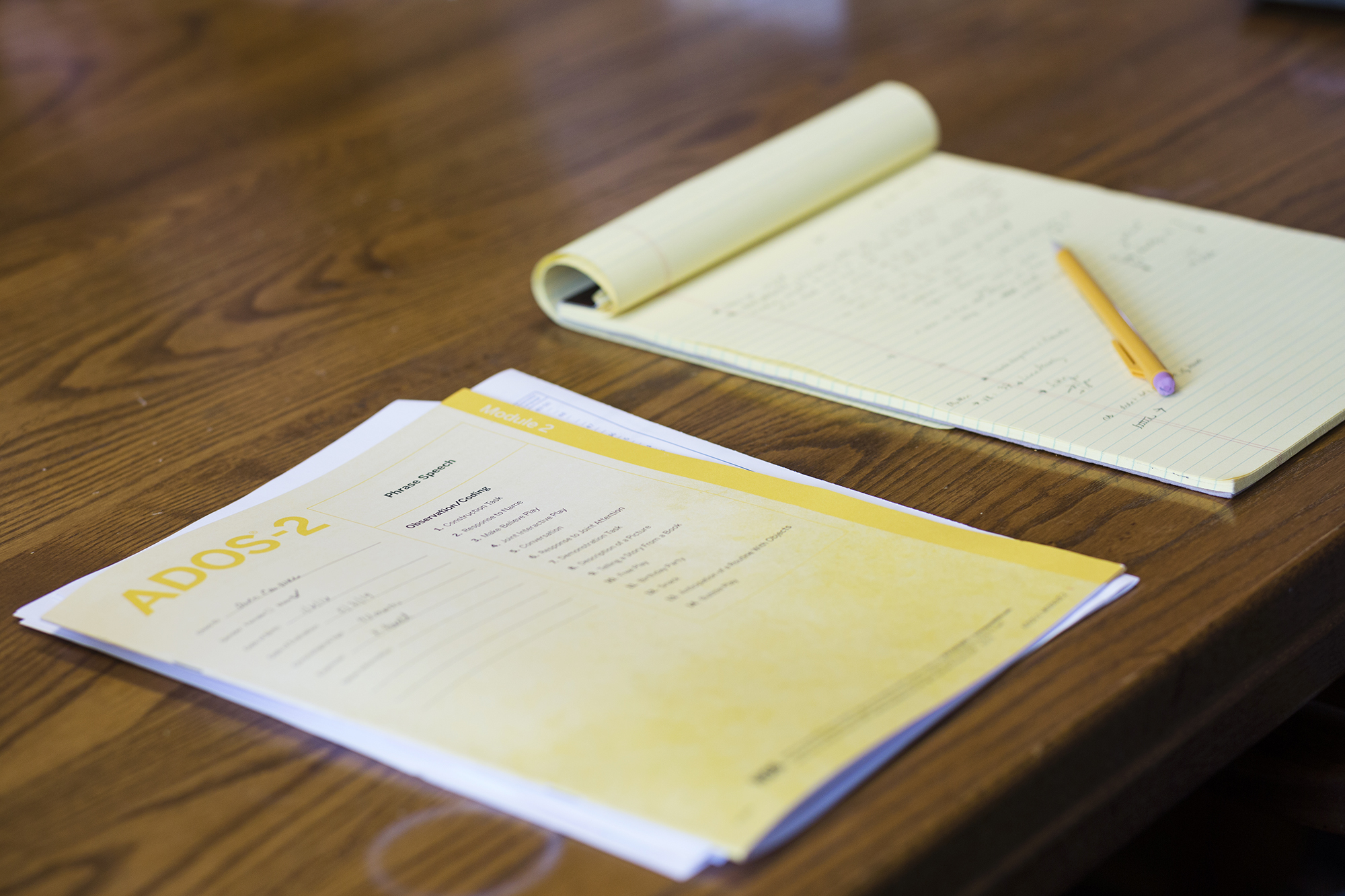

Gold standard: Owen’s evaluation includes standardized autism tests.

Tough result: After the tests are complete, clinicians deliver Owen’s autism diagnosis to his parents.

6:56 a.m.

C

outure merges into traffic on a highway heading northeast and lowers her visor to block out the rising sun. Owen dons a pair of black sunglasses and then turns to look out the passenger window, where he catches sight of his own reflection. “Is that Owen?” he asks.His mother glances up at him through the rearview mirror. “Owen, what do you see outside?” she asks. “Do you see anything now?”

“Now!” he shouts.

Owen frequently refers to himself in the third person, misuses pronouns and compulsively repeats words, a phenomenon called echolalia — language problems that are all associated with autism. Around the time of his third birthday, in January, Couture described Owen’s speech to his pediatrician, who referred him to a speech therapist.

A month later, the speech therapist evaluated Owen’s language skills and found them to be delayed. She scheduled him to receive one-hour weekly speech therapy, and her office recommended he see an autism specialist. Couture burst into tears upon hearing her suspicions finally validated. Then she went home to call Owen’s pediatrician. She also scoured the internet for what to do, she recalls. “It’s really hard to navigate what to do next. You can’t just Google: ‘Where do I get autism testing?’”

The internet, of course, is full of misinformation. But there is also trustworthy information available. Shulman recommends a website called Learn the Signs. Act Early, created in 2011 by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The site’s goal “is to empower everyone who has contact with young children to engage in developmental monitoring,” says Shulman, who was involved in the program. “As soon as the parent is concerned, it means that something must be done.”

Owen saw an autism specialist within months of his referral. The Coutures were lucky they lived relatively close to the Yale Child Study Center, a clinic in New Haven, Connecticut, that specializes in conditions of brain development. And the center had an opening to see Owen at the end of May.

Many families are much less fortunate. It’s not uncommon for families to wait a year or more to get an appointment, says Jeremy Veenstra-VanderWeele, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University. “It’s excruciating,” he says. “You can only imagine as a parent, [if] somebody says they think your child might have autism, but you’re going to have to wait more than a year to find out for sure.” This wait can be particularly agonizing because children cannot get the help they need until they have a diagnosis.

One reason for the delay is that the diagnostic process usually takes several hours, if not days, and calls for one or more highly-trained clinicians. Experts like these are scarce outside of big cities; they are all but nonexistent in some parts of the world.

Owen’s diagnostic evaluation included a battery of tests over the course of two days. He scored just below average for children his age on problem-solving and fine motor skills, due in part to his difficulties with understanding instructions and imitating others. Another test revealed that he has trouble with social communication and engaging others. On the plus side, his language abilities had improved into the average range, perhaps because of the speech therapy he had begun.

Shortly after noon on the second day, the Coutures had their answer: Owen has mild to moderate autism, the team at Yale told them. The news “hit me like a brick wall,” Couture says. Like many parents, she worried at first about her son’s future and wondered whether he would ever be able to live on his own, hold a job, get married or have children. Within a week, though, she began to see things differently: “His brain is amazing. As long as we figure out a way to guide him to use that brain in a way that is really valuable to him, he actually is going to be an amazing human being,” she says.

Couture also started to feel better because the diagnosis brought her some much-needed closure. “No one believed me; everyone kept saying, ‘He’s just behind, he’s just not there yet, and in six months to a year he’ll be at the same level [as his peers],’” she says. “Everyone would always say, ‘You worry too much,’ and that was so frustrating and hurtful to me.” After the diagnosis, she no longer worried that she might be a “crazy, obsessed mom.” Still, she was filled with frustration at the delay in getting her son the help he needs. “If we had gotten this diagnosis a year ago, when I really started to ask questions, he would already be at Prism, and would have already been at Prism for a year,” she says.

There is no guarantee that that year would have made a difference. A few studies that have tracked autistic children over time hint that those who have behavioral therapies early in life tend to do better in the long term. But these studies do not prove, Lord notes, that the earlier a child begins autism therapy, the more effective it will be.

7:16 a.m.

C

outure pulls the car into Prism’s parking lot and parks in one of two designated drop-off zones. Within a minute, a young man and woman emerge from the building. They wave and smile as they approach the car. Owen unbuckles his seatbelt, stands and peers out the window, and then repeatedly slaps his palms against the glass.“What’s up, dude?” says Anton Yurack, one of Prism’s behavior analysts, as he opens the rear car door. “I like your cool sunglasses.”

Owen takes the glasses off and turns his head toward his mother in the driver’s seat, his eyes wide and lower lip quivering. “Give me kisses, I love you,” she says.

“Say, ‘Bye, Mom,’” Yurack tells Owen.

“Bye, Mom,” Owen says.

Yurack counts out loud to three and then lifts Owen out of the car and places him in front of Kayla Stinson, a behavioral technician who will be Owen’s one-on-one instructor at Prism. She kneels on the sidewalk and shows Owen a cartoon drawing of footprints. Then she points to a trail of larger but otherwise identical footprints laid out along the sidewalk.

“Guess what?” she says. “Follow these footsteps and you get … ” She shows Owen a picture of Hershey’s Kisses, one of his favorite treats. He takes her hand and the two of them walk toward the building. Yurack grabs Owen’s backpack, lunchbox and Bearsie from the back seat and follows after them.

Couture watches from the car, relieved that this drop-off game she planned with Yurack and Stinson has gone off without a hitch. Then she moves the car to a nearby parking spot to make some work calls. She waits in the parking lot for 45 minutes until she is sure that Owen has settled in.

It doesn’t take him long. Inside the building, Owen sits down at a table in ‘Treatment room 1,’ where he’ll spend much of his time in the coming weeks and months. He enjoys his chocolate reward while Yurack empties the contents of his backpack onto a shelf. Bearsie plays a slower-than-usual melancholic rendition of its lullaby, and in response Owen mumbles, “He doesn’t work.” Stinson sets out to change the toy’s batteries.

“Hey, look, let me show you something. What does this say?” Yurack says, pointing to a small label on the shelf.

“O-W-” Owen says, spelling out the letters. “This says … ,” Yurack says, prompting him. “Owen!” “Owen!” “You got it! O- … ,” Yurack begins. “W-E-N,” Owen replies.

Owen hangs his backpack on a peg as instructed, and then runs toward a trampoline. He jumps on it for a few minutes as Stinson sings, “Five little Owens jumping on the bed.” Next, Owen darts across the room and dives into a ball pit, giggling. Soon after, he climbs into a pedal-powered toy car and careens down the hallway. These activities may look like play, Yurack says, but they offer the team an opportunity to gather information about Owen’s likes and dislikes and to determine which activities motivate him.

For now, their primary goal is for Owen to get comfortable in his new surroundings and have fun. But soon they’ll begin to engage him in his favorite play activities while teaching him crucial communication and motor skills.

This approach is based on the Early Start Denver Model, a form of applied behavior analysis. The therapy was shown to improve cognitive abilities, daily-living skills and language skills in one controlled study, but a follow-up study did not confirm the finding. Owen is supposed to receive up to 35 hours of autism therapy at Prism each week. His parents also plan to attend a weekly session there to learn how to apply some of the teaching strategies at home. And Yurack’s goal is to evaluate Owen’s progress every week and adjust the therapy accordingly.

8:08 a.m.

O

nce she is sure Owen is okay, Couture starts the car. “He did great,” she says. “He looked like he was going to start bursting into tears when he first got out of the car, and then they distracted him with their little game.”Owen is supposed to stay at Prism until noon today. But once he has grown used to the center, he will stay for roughly eight hours each weekday. His father will handle drop-off because the center is on his way to work.

Children like Owen can attend Prism until they are 7 years old. Couture holds out hope that one day she and her husband will be able to enroll Owen in a mainstream school closer to home. “We live in Cheshire because it has a great school system, ironically,” she says. Still, she worries that Owen will not fit in socially in a mainstream school and might be a target of bullying. The other options, she says, are a special-education classroom or a therapist who comes to the home.

Most children start at Prism six to eight weeks after their family applies, says Rebecca Giammatti, co-founder and chief clinical officer at the center. It took nearly twice as long in Owen’s case because his family’s insurance declined to cover the full 40 hours per week of therapy that his doctors had recommended. Giammatti says her team sees insurance denials in up to 70 percent of cases, although they do not always take as long as Owen’s to overturn.

The staff at Prism handled the insurance appeals process, and the Coutures’ insurance plan eventually agreed to cover 35 hours per week at the center. The family will pay a co-pay of $30 a day — at least until they reach the plan’s limit for out-of-pocket expenses, which Couture estimates will happen after four months.

They’re lucky that the expense is less than what they spent on daycare, because the cost is prohibitive for many other families with an autistic child. The services covered by insurance in the U.S. vary tremendously from state to state, Shulman says, in part because different states have different mandates. “Where you live really determines what you get,” she says.

For families who don’t have private insurance, centers like Prism are not always an option. Giammatti estimates that the annual cost of services like Owen’s can reach six figures. U.S. federal law mandates that public schools must provide special-education services to autistic children. But again, what a child actually receives varies dramatically depending on where the child lives.

8:45 a.m.

B

ack at home after the drop-off, Couture settles into a living-room chair to relax and check her email. She runs her own event-planning business part-time and also works part-time for a medical recruiting firm. She wonders out loud how other parents navigate the route to autism diagnosis and services while juggling other responsibilities. Studies suggest that many parents of autistic children stop working to care for their child.“I work from home, and it’s flexible,” she says. “I can work on a Sunday if I want to make up time, and that has really helped with the whole situation with Owen. [Otherwise] I don’t know what I would do. I feel like I would have to leave whatever position I was in, because it’s a lot of appointments.”

For now, Couture is looking ahead and hoping for a good outcome. “Considering the vast improvement that’s happened since his testing at Yale to now, I can’t even imagine or fathom what he’ll be like when he’s at Prism five days a week for two years,” she says.

Her phone whistles with the arrival of a text message. It’s from Yurack, who has sent a video of Owen with a big grin on his face, riding a tricycle down a hallway at Prism. Couture coos with delight.

Then, within seconds, she gets a second message, recommending that she return to pick Owen up at 11 a.m. — an hour earlier than planned. The text doesn’t explain why, but Couture guesses that Owen is tired. Still, she is eager to focus on the positive. It’s a start — and hopefully Owen is ending his first day of therapy happy.

Hannah Furfaro contributed reporting to this article. Part 2 will revisit the Coutures to see how Owen is doing a year after his diagnosis.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025