One form of immune gene tracks with autism traits

A variant in a gene that regulates immune responses is more common in children with autism than in those without this disorder.

A variant in a gene that regulates immune responses is more common in children with autism than in those without this disorder. The unpublished results, presented today at the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago, add to mounting evidence implicating the immune system in autism.

“We think the immune system is important during embryonic and fetal neural development,” says Nina Strenn, graduate student in Agneta Ekman’s lab at the University of Gothenburg’s Sahlgrenska Academy in Sweden, who presented the results. “If you have immunological genes that have a slightly different function, the entire brain may connect in a different way.”

To look at the association between immune gene variants and autism traits, Strenn and her colleagues used data from the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden. The study includes DNA sequences and behavioral information from more than 12,000 Swedish children between the ages of 9 and 12.

The researchers focused on two genes known to play a central role in immune responses: NFKB1 and NFKBIL1. They looked for common variants in the genes called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

They identified four SNPs in NFKBIL1. Children with one of the SNPs are more likely to meet the criteria for autism than those with a different DNA letter at that location. The effect was stronger when the researchers looked at boys alone.

A second SNP in NFKBIL1 tracks with autism-like traits in children who don’t meet the threshold for an autism diagnosis. This SNP is also associated with language impairments, the researchers found.

The researchers also associated an SNP in NFKB1 with autism, but this connection disappears when the analysis is more stringent.

The findings suggest that subtle variations in a gene’s sequence can impact its role in the brain.

“None of these polymorphisms actually changes the protein structure,” Strenn says. “But they can change, for example, how much of the protein will be expressed.”

The researchers hope to replicate their findings in a separate group of children with and without autism. They would also like to study the effects of NFKBIL1 variants in cultured cells.

“It would be really interesting to see if the polymorphism causes the protein to be more or less expressed,” she says.

For more reports from the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

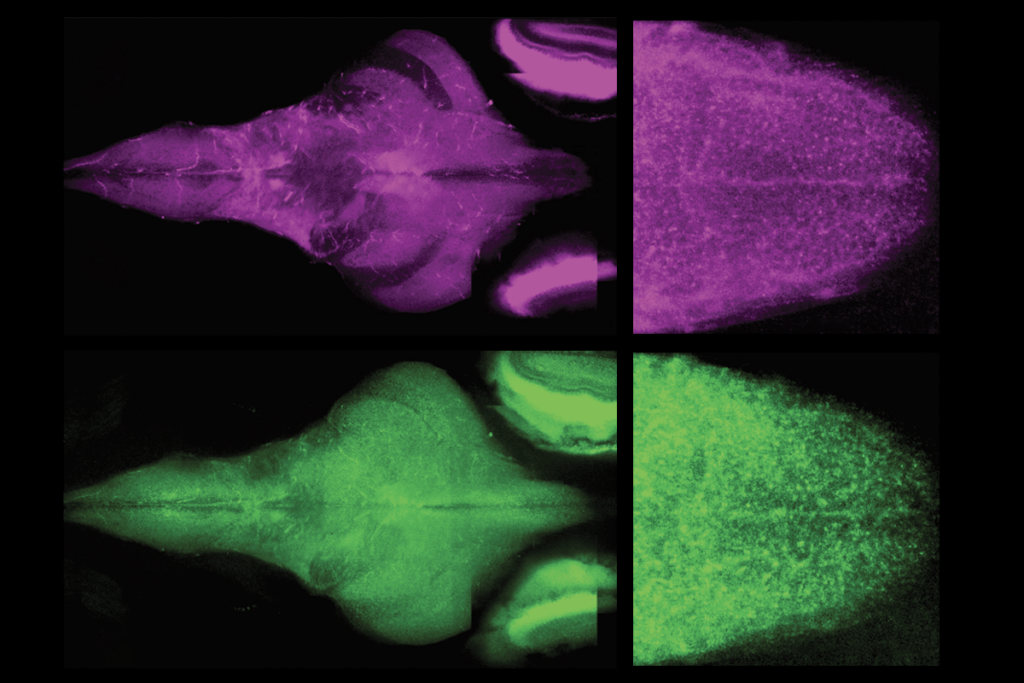

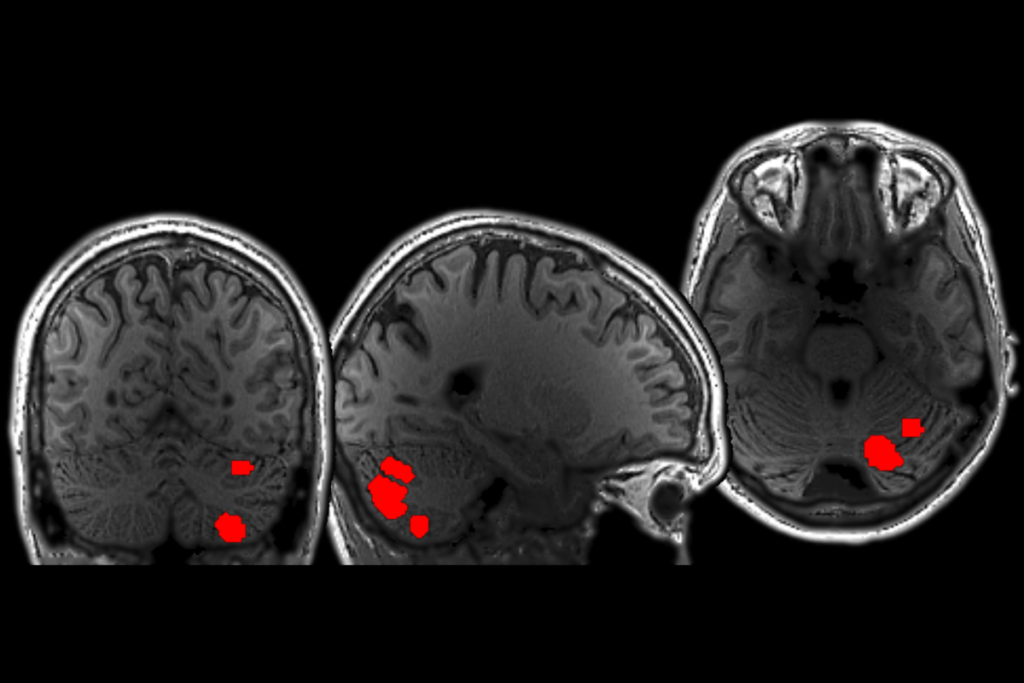

Cerebellum responds to language like cortical areas

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles