M

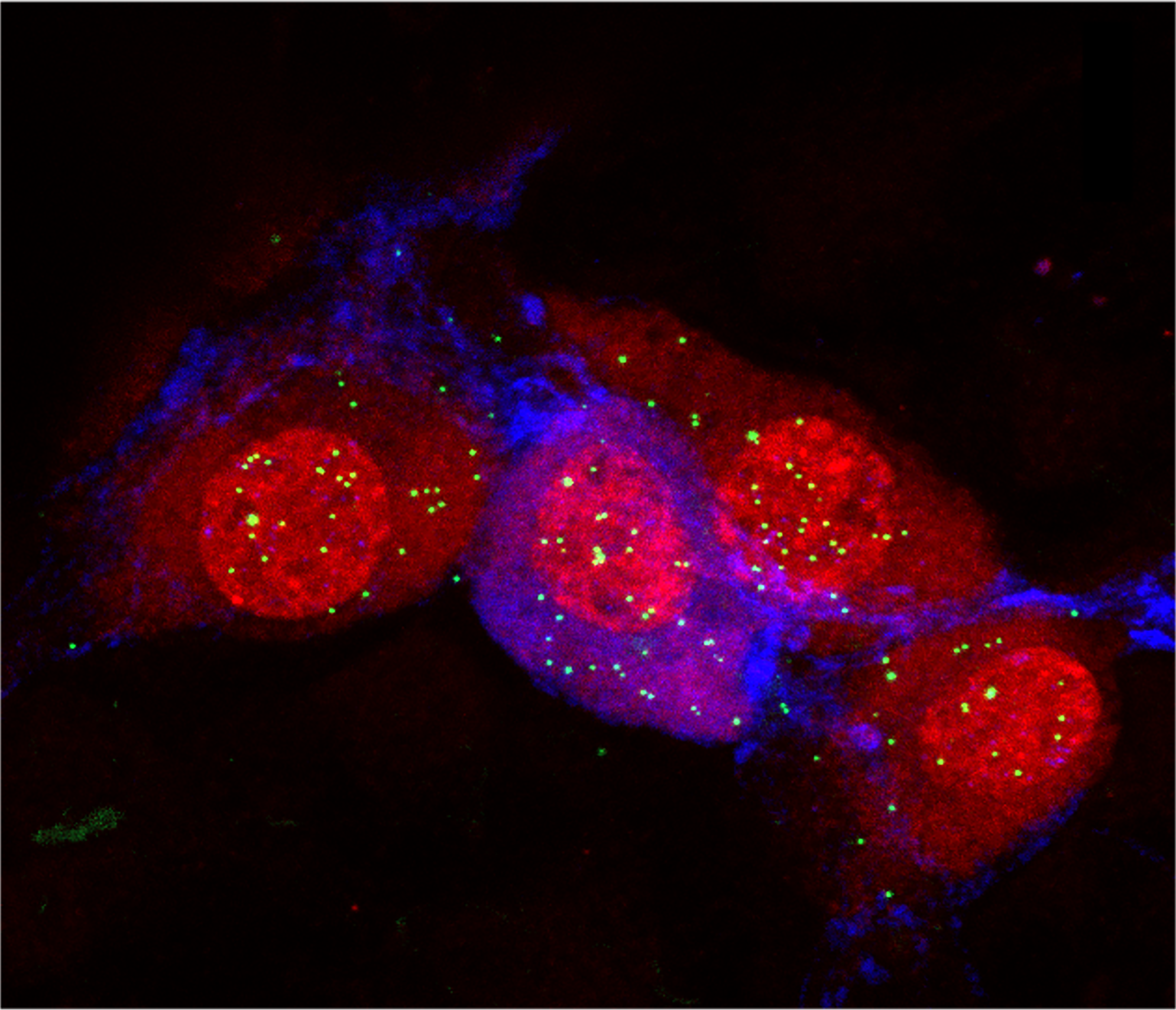

any papers about autism-linked genes note that the genes are expressed throughout both the central and the peripheral nervous systems. The proportion of such prolific genes may be as high as two-thirds, according to one 2020 analysis. Yet few studies delve into what those genes are actually doing outside the brain.That’s starting to change. Although autism is typically thought of as a brain condition, a critical mass of researchers has started to investigate how the condition alters neurons elsewhere in the body. Their work — part of a broader trend in neuroscience to look beyond the brain — hints that the role of the peripheral nervous system in autism is, well, anything but peripheral: Neuronal alterations outside the brain may help to explain a host of the condition’s characteristic traits.

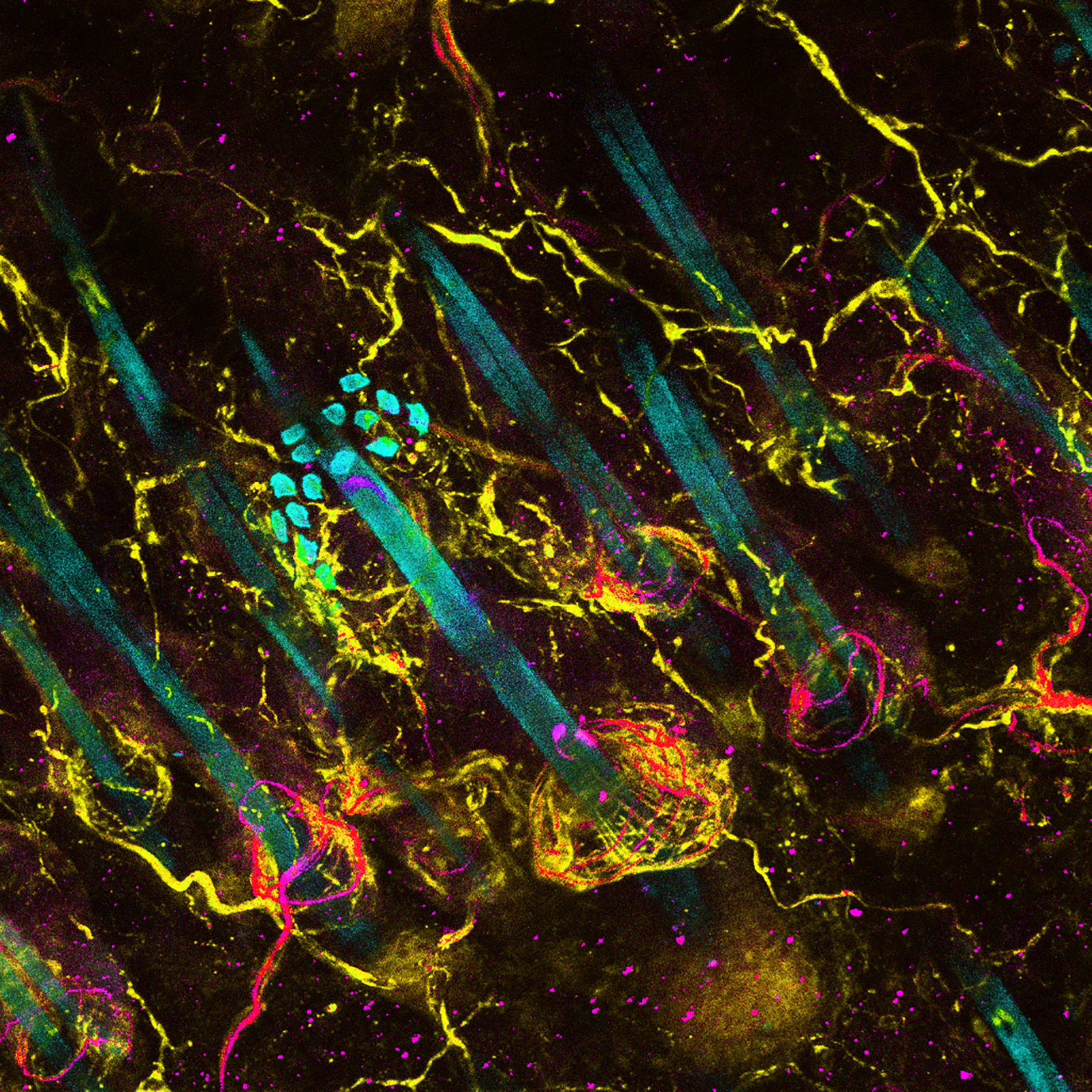

Much of the research so far focuses on touch and the workings of the gut, but there is increasing interest in other sensory and motor neurons, as well as the autonomic nervous system, which orchestrates basic body functions such as heartbeat, blood pressure, breathing and digestion.

It’s difficult to pinpoint whether some autism traits arise in the peripheral nervous system or the central nervous system; in many cases, complex feedback loops link the two. “Your nervous system doesn’t know that we’ve divided it that way,” says Carissa Cascio, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

But at least some peripheral changes may offer novel treatment targets. And drugs that act in the peripheral nervous system could also prove more effective and have fewer side effects than brain-based therapies, says Julia Dallman, associate professor of biology at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida.

“I think there’s actually a lot of opportunities for peripherally targeted treatments,” says geneticist Lauren Orefice, assistant professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital. “It’s interesting because it is the opposite of what we’ve tried to do in neuroscience for a really long time” — that is, getting drugs into the brain.

This new focus on the periphery is already prompting fresh thoughts about old data, says Elisa Hill-Yardin, a neuroscientist at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. When she set out to investigate the role of autism-linked genes in the gut, for example, the NLGN-3 mouse was one of few autism mouse models available. When she discovered gut problems in the mice, she reached out to the doctors who had cared for the first children identified with NLGN-3 mutations.

“And lo and behold, those two boys, who are now adults in Sweden, both had really quite serious gastrointestinal dysfunction,” Hill-Yardin says. The details had “been beautifully recorded” by the doctors but went unmentioned in the report because they seemed irrelevant in characterizing an autism-related gene.

Here we take you on a quick tour of some of the different lines of evidence linking autism to the peripheral nervous system.