Welcome to the first edition of the Null and Noteworthy Newsletter! We read a lot of papers here at Spectrum, and although we tend to focus our coverage on those with new findings, sometimes well-conducted studies lead to null results or produce replications. Those can be at least as valuable as exciting advances — and they demonstrate how science works. In this newsletter, we will round up papers that do the vital work of reproducing a previous result or reporting the absence of one.

Let us know what you think of the newsletter, or tell us about your own results, at [email protected].

Boys and girls:

Autism’s sex bias is well known: The condition is diagnosed in boys four times as often as in girls. Some research suggests that this bias is due to differences in how autism presents in people of different genders. But one new study seems to contradict that conclusion. Evaluations of 1,480 autistic preschoolers and 593 with some autism traits, all of whom are part of the Study to Explore Early Development, found no differences between boys and girls in behavior, development, scores on an autism screening test or diagnoses of other developmental conditions. In fact, the boys and girls were “more similar than different,” the researchers wrote. The majority of the autistic children in the study also had intellectual disability and language delays; most of the non-autistic children did not have intellectual disability, but their parents had reported language delays. It’s possible that sex differences may emerge later in life in children with these traits, the researches write.

The findings appeared in Research in Developmental Disabilities in February.

Child’s play:

For children, playtime is serious business: It’s one of the primary ways they learn about their world. Autistic children may approach play differently than non-autistic children, and some research has suggested these differences arise from variations in the toys and situations that draw their attention. To test this theory, researchers fitted 14 autistic and 15 non-autistic children with a wearable eye tracker to follow their gaze as they played with a caregiver. The study found no differences in what the children chose to focus on, the actions they took or how they coordinated their behavior with the caregiver. The researchers suggested that naturalistic settings and measurement techniques, like the ones they used, are needed to elucidate how autistic children play and learn.

The findings appeared in Scientific Reports in February.

Unfolding autism and ADHD:

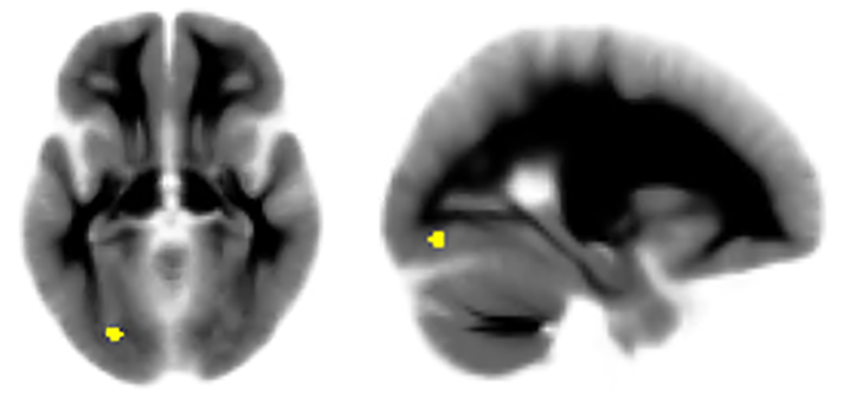

Autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often overlap, making it difficult to disentangle their biology. A new review probed the patterns of brain folds, known as gyrification, in the cortex of people with either condition. Across 24 papers — 20 focused on autism — the researchers found no differences in cortical gyrification between controls and people with either condition. It is possible these differences really don’t exist. It’s also possible, however, that they are too subtle or varied to be picked up in such a research review, the researchers noted. Differences may only emerge in controlled studies using the same protocols to compare people with the two conditions.

The work was published in Cerebral Cortex in December.

Face to face:

Autistic people tend to make less eye contact than non-autistic people do. But is that because autistic people focus on mouths, rather than eyes, when looking at others’ faces, as some studies have suggested? No, according to a recent study of 21 boys with autism and 21 without that used a combination of eye-tracking and electroencephalography. The researchers found that both groups spent more time looking at the eyes of a flickering face than its mouth, and autistic people’s neural responses indicated neither a disinterest in nor a fear of the eyes, though the group did show some differences in the amount of time spent looking at other facial features. Although there may still be an explanation for the different gaze patterns in autistic and non-autistic people, the “excess mouth/diminished eye gaze” hypothesis isn’t it, according to this work.

The findings appeared in Molecular Autism in November.

Sound off:

Research on the brain’s responses to sounds in autistic people could shed light on auditory sensitivities and language difficulties associated with the condition. But so far, findings have been mixed: Some show that autistic people have delayed neural responses to sounds, compared with non-autistic people, but others don’t. The first review of the relevant literature shows that most differences in sound responses between people with autism and those without are small, and studies on the subject vary in quality. Some observed delays may be driven by a subset of autistic people — those who are minimally verbal, for example — making it difficult to know whether the findings can be generalized across the spectrum.

The review was published in Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging in September.