New mutations spike in offspring of older fathers

The offspring of older male mice are 16 times more likely to harbor a spontaneous copy number variation — a deletion or duplication of genetic material — than are the offspring of young males, according to a new study.

Researchers have for the first time found experimental evidence linking older fathers to a higher risk of autism in their children.

A study published online on 30 August in Translational Psychiatry reports a higher risk of de novo mutations in the offspring of older male mice1. De novo mutations are not inherited but arise spontaneously in the ovum, sperm or fertilized egg.

Older male mice, equivalent to about age 50 in humans, produce offspring that are 16 times more likely to harbor a de novo copy number variation (CNV) — a deletion or duplication of genetic material — than are the offspring of control males, the researchers say.

In the study, researchers mated 3-month-old females with either males of their own age or much older 12- to 16-month-old males. They found six de novo CNVs among the 60 offspring of the older fathers. These CNVs encompass genes that have been linked to autism, schizophrenia and brain development.

By contrast, researchers did not identify any CNVs in the 69 offspring of the younger males.

Epidemiological studies have reported that older men have a higher risk of fathering a child with autism. According to a 2010 study, a man’s chance of fathering a child with autism begins to rise at age 30: The risk of having a child with autism is four times greater for men older than 55 than for men under 302.

The new study does not provide direct evidence that the de novo CNVs identified originated in the male germ line. But because the age of the mothers was the same in both groups, the researchers say, it suggests that the CNVs arose in the sperm.

“We are fairly confident that the de novo CNVs were from the father, because they were all in the offspring of older males,” says lead investigator John McGrath, professor of epidemiology and developmental neurobiology at the University of Queensland in Australia. “If the mother were contributing CNVs, or if the CNVs were somatic mutations post-fertilization, then these would be evenly distributed in the offspring of young and old sires.”

New mutations:

Several studies have shown that people with autism or schizophrenia carry more spontaneous harmful mutations in their genome than do typical controls3,4.

For instance, two new CNV studies published in Neuron in June turned up de novo mutation rates of 5.8 percent5 and 8 percent6 in individuals with autism. Those studies were carried out in so-called simplex families, in which only one child is affected by autism. The de novo mutation rate in unaffected siblings is just two percent, the studies found.

“There is robust evidence that CNVs are associated with autism and schizophrenia,” McGrath says.

Another study of simplex families, published in Nature Genetics in May, found four de novo mutations in autism-linked genes in 20 children with autism7. The mutations in this case were single-base changes in the exome, or protein-coding regions of the genome.

Epidemiologists have reported a higher risk of autism in the children of older fathers, but so far there has been little biological evidence to support that theory.

“It is indeed an exciting step forward to find that de novo events are increased in the aging male germ line,” says Dolores Malaspina, professor of psychiatry and environmental medicine at New York University Medical Center, who was not involved in the study.

Malaspina studies paternal age effects in schizophrenia, which is believed to be four times more prevalent in children of older fathers. “While we do not yet know if these are causative changes or just reflect chromosomal instability, [the findings] clarify that paternal age-related risk does not reflect psychological or other genetic vulnerabilities in the fathers themselves,” she says.

The field has been expecting findings like these for some time, researchers say. Because women are born with all of their eggs, whereas men produce sperm throughout their lifetimes, the risk of mutation in the germ line is higher for males.

“The biological challenge for older males is ongoing sperm replication,” says Jay Gingrich, associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University in New York. “It’s one of the most actively dividing cells in the body,” he says.

By age 55, the DNA in sperm has undergone some 800 cycles of replication; in the case of the older mice, the sperm would have undergone about 120 cell cycles.

Suggestive associations:

Factors other than simple cell division could also contribute to the higher risk of mutation in the male germ line.

“Some of the other systems in place to ensure the fidelity of replication, like proofreading, may be slipping as time goes on,” Gingrich says. His team is investigating epigenetic mechanisms — which can turn genes on or off without altering the genetic code — in older fathers and their offspring.

In the new study, one of the de novo deletions includes a gene called AUTS2. This gene has previously been reported to be differentially methylated — an epigenetic change that alters gene expression by adding a methyl group to DNA — in people with schizophrenia.

The deletion is on mouse chromosome 5, which parallels human chromosomal region 7q11.22. This region has been associated with schizophrenia, autism, bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and alcoholism.

Another deletion present in four offspring in the study maps to human chromosome 10. Mutations in three genes in the region have been found in one person with schizophrenia and two with autism. Two other CNVs affect the MID1 gene on the X chromosome. Loss of function in the MID1 gene causes Opitz G/BBB syndrome, which leads to birth defects and intellectual disability.

The researchers found that some of the CNVs have clear behavioral effects. In an earlier study, McGrath’s team reported that the offspring of older male mice have a thicker cerebral cortex and show more anxiety8. In the new study, he found that the six female offspring with duplications in MID1 have a smaller striatum, a brain region associated with addiction and other neuropsychiatric disorders. They also show more head dipping, a marker of exploratory behavior.

Still, like all studies of this sort, the findings need to be replicated, Gingrich points out. “The numbers need to be a little higher,” he says. “But the take-home message is that these CNVs are being introduced into the population via the older fathers.”

References:

1: Flatscher-Bader T. et al. Transl. Psychiatry 1, e34 (2011) Article

2: Hultman C.M. et al. Mol. Psychiatry Epub ahead of print (2010) PubMed

3: Itsara A. et al. Genome Res. 20, 1469-1481 (2010) PubMed

4: Awadalla P. et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87, 316-324 (2010) PubMed

5: Sanders S.J. et al. Neuron 70, 863-885 (2011) PubMed

6: Levy D. et al. Neuron 70, 886-897 (2011) PubMed

7: O’Roak B.J. et al. Nat. Genet. 43, 585-589 (2011) PubMed

8: Foldi C.J. et al. Eur. J. Neurosci. 31, 556-564 (2010) PubMed

Recommended reading

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

Explore more from The Transmitter

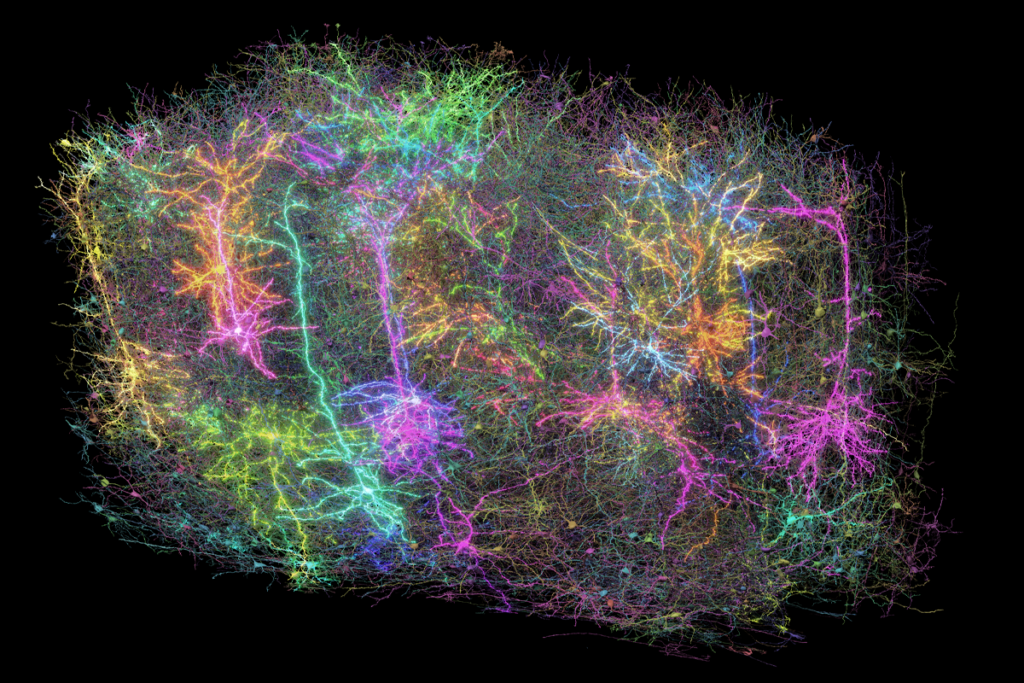

Inhibitory cells work in concert to orchestrate neuronal activity in mouse brain

Aran Nayebi discusses a NeuroAI update to the Turing test