A new atlas of molecular and cellular dynamics in the human neocortex offers an unprecedented look at the development of certain cells from the first trimester of pregnancy through adolescence. The work shows how typical development progresses and identifies cell types with links to autism and glioblastoma.

“It’s a big contribution to the field,” says Xinyu Zhao, professor of neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was not involved in the work.

Unlike similar tools, the resource incorporates gene-expression levels and chromatin accessibility in the same single cells and across a wide range of ages. The approach can also illuminate some of the earliest changes linked to neurodevelopmental conditions, including autism, the study investigators suggest.

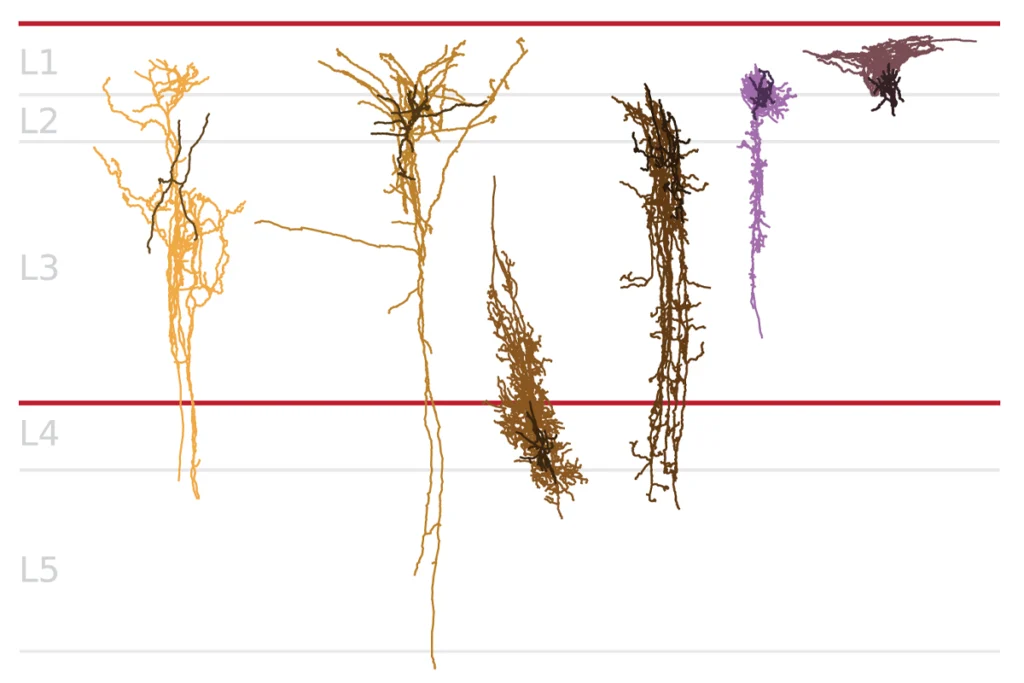

For example, a particularly large number of genes and genetic regions linked to autism are available to be used by certain excitatory neurons—immature cells and their mature counterparts, found in layer 6 of the cerebral cortex—that project to other parts of the cortex, and more broadly to the telencephalon. Similar neurons in layers 2 and 3 of the cortex also have high numbers of differentially expressed genes in people with autism, as shown in a 2019 study.

Putting the work together suggests that intratelencephalic neurons across all layers are affected, says study investigator Li Wang, a postdoctoral scholar in Arnold Kriegstein’s lab at the University of California, San Francisco.

On the other hand, these same genes and genetic regions are less available to be used by inhibitory neurons, the new research shows. That’s a departure from several other conditions that the researchers looked into, including bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, which were linked to both excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Like autism, major depressive disorder was linked only to excitatory neurons.

Genes expressed by neurons linked to autism are especially active during the second trimester of pregnancy, the study showed. That confirms past findings that link autism to the second trimester, Zhao says.

In the new study, that finding was derived using a recently developed technique called SCAVENGE, which maps genetic variants identified through genome-wide association studies onto single-cell data to shed light on those variants’ biological functions. The researchers used this tool to consider more than a million genetic variants previously linked to autism.

T

he team obtained 38 samples of human neocortex from tissue banks and hospitals. The samples spanned all three trimesters of pregnancy as well as the early postnatal stage and adolescence.That’s not easy, says Shawn Sorrells, assistant professor of neuroscience at the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the work. “It’s challenging to obtain the samples. It’s challenging to get them at the highest quality needed to be able to do this kind of work. And it’s a really impressive feat to have collected samples across this wide an age range.”

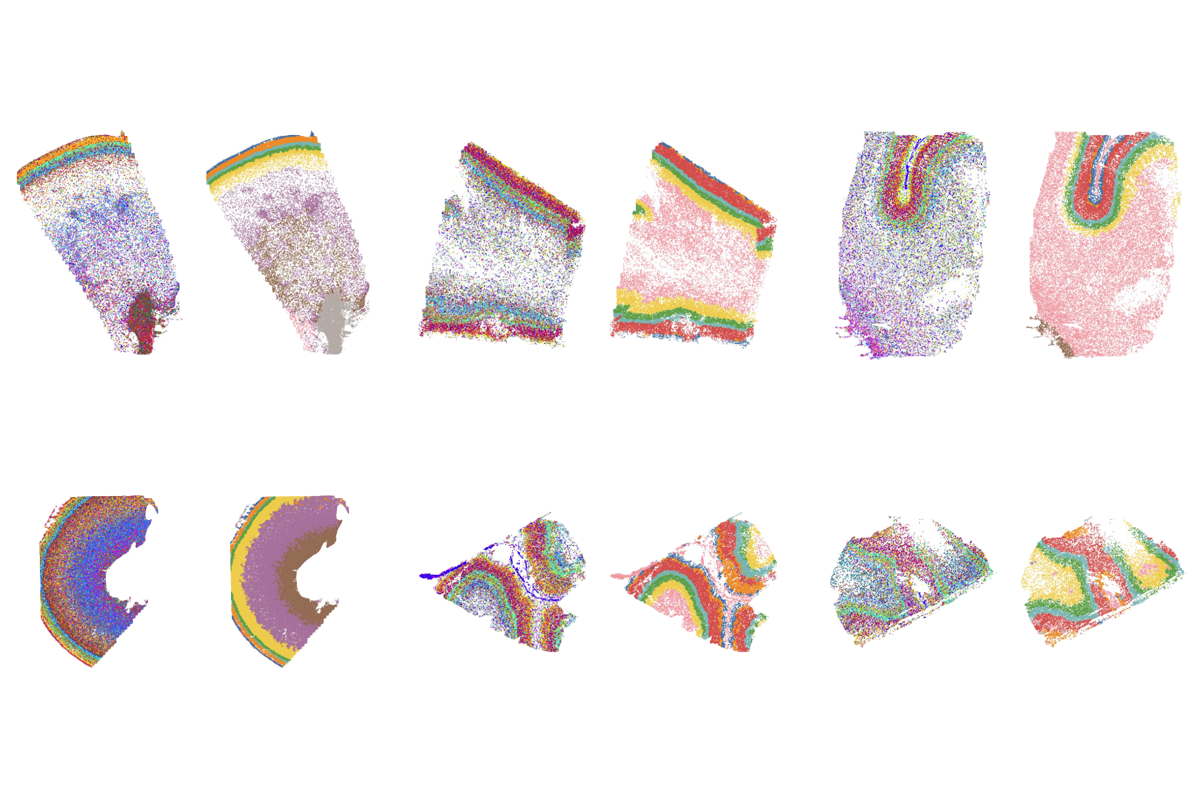

The researchers grouped individual brain cells according to the genes they express and the regions of their chromatin that are “open,” or available to be used by the cell. Some 33 distinct types of cells orchestrate brain development, including excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, radial glia and macroglia, the researchers found. The results were published this month in Nature.

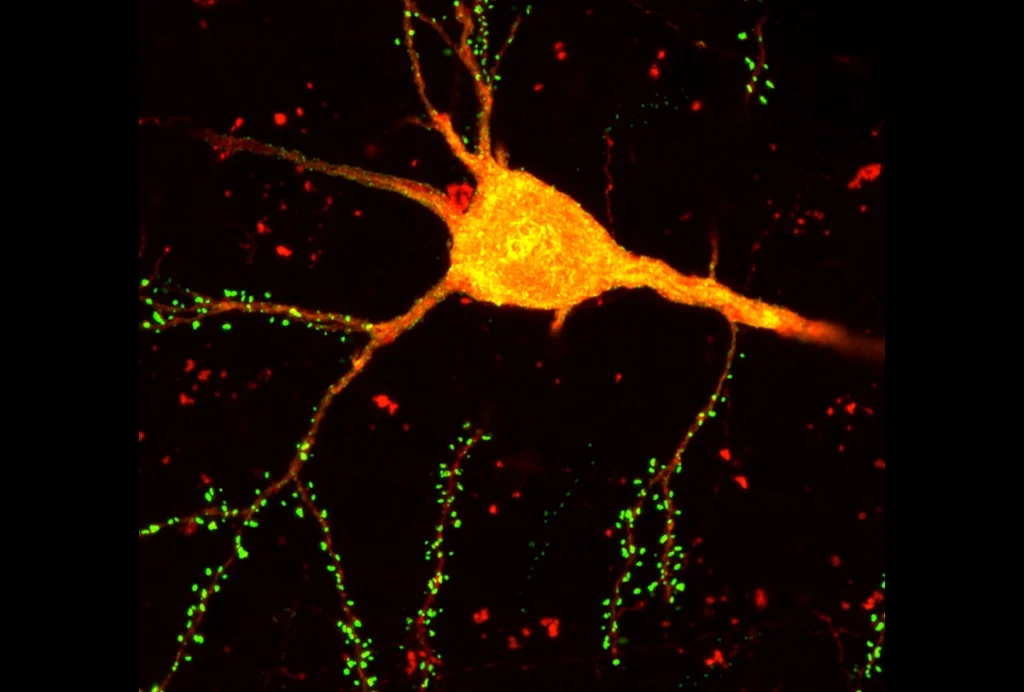

One of these cell types—which the researchers call “tripotential intermediate progenitor cells” (TriIPCs)—can become GABAergic interneurons, oligodendrocyte precursor cells or astrocytes in cell culture, the study showed. That TriIPCs become inhibitory came as a surprise, says lead investigator Arnold Kriegstein, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, because it has long been established that most inhibitory cortical interneurons form outside the cortex and then migrate in.

The results suggest that similar cells may form within the cortex itself, by way of TriIPCs. But more research is needed to be sure, Wang says.

To further define the roles of TriIPCs, the researchers did “this really neat experiment,” Sorrells says. They isolated TriIPCs from people and then implanted them in the brains of mice and let them differentiate for 12 weeks. At the end, the researchers could see that inhibitory neurons had formed, along with oligodendrocytes and astrocytes.

T

he atlas also contains a clue to the origins of glioblastoma—a type of brain cancer that usually proves fatal within 18 months of diagnosis. The TriIPCs bear a striking resemblance to glioblastoma cells and could become a target for future therapies, Wang says.Researchers have previously hypothesized that the precursors of each individual cell type within glioblastoma might give rise to these tumors, but a simpler explanation is that all the cells within the tumor come from a single, multipotent cell type, Kriegstein says. Still, the findings are preliminary, he adds.

Moving forward, Wang says he would love to see this developmental atlas used to examine how rare genetic variants that are associated with autism—which have long been studied—interact with the broader range of variants that he and his collaborators analyzed, including some that are common in people.

Kriegstein says he is excited to see the hundreds of genetic variants associated with autism coalesce around common cell types and signaling pathways. He thinks this will show that autism is “not 100 different diseases. It’s more like a handful of processes which can be altered in different ways by each of these different mutations.”