New evidence ties Hans Asperger to Nazi eugenics program

The Austrian doctor Hans Asperger cooperated extensively with the Nazi regime and may have sent dozens of children to their deaths.

The Austrian doctor Hans Asperger cooperated extensively with the Nazi regime and may have sent dozens of children to their deaths.

Horrific details of his involvement were revealed yesterday in the journal Molecular Autism and will be detailed in a forthcoming book called “Asperger’s Children: The Origins of Autism in Nazi Vienna.”

Asperger was among the first researchers to describe autism, and his decades of work with children later informed the concept of an autism ‘spectrum.’

Scholars have raised questions about his associations with the Nazi Party and his involvement in Nazi efforts to euthanize children with certain health conditions or disabilities.

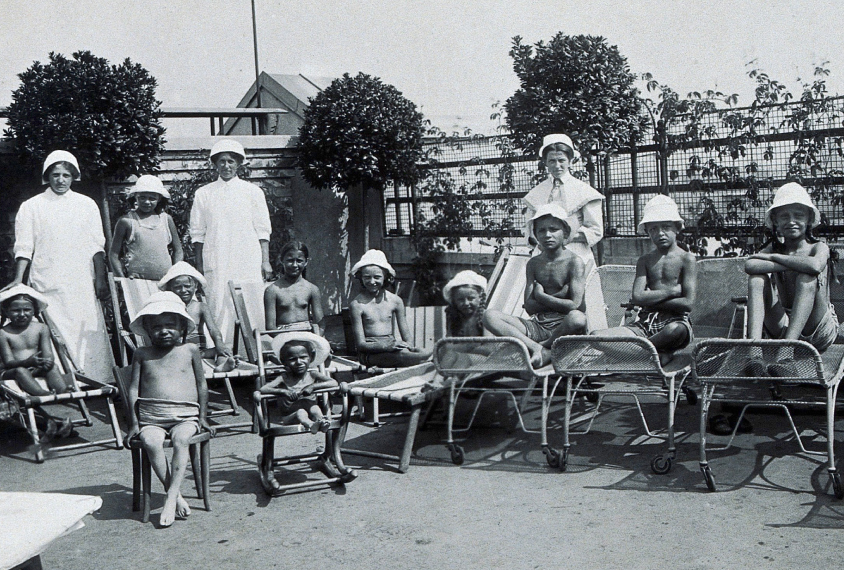

The new book and paper suggest that Asperger referred dozens of children to a clinic called Am Spiegelgrund in Vienna, where doctors experimented on children or killed them1. Nearly 800 children, many of whom were disabled or sick, were killed there. The clinic’s staff gave the children barbiturates, which often led to their death by pneumonia.

Reacting to this news, some experts say the eponymous medical term ‘Asperger syndrome’ should be discarded.

The “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM-5) has already dispensed with Asperger syndrome for other reasons, notes David Mandell, professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Asperger [syndrome] was put in a coffin with the DSM-5, and maybe this information will be the final nail in terms of preventing it from coming back,” he says.

Others are more cautious, saying the stain on Asperger’s name shouldn’t erase his contributions to the understanding of autism.

“I don’t think erasing history is an answer,” says Herwig Czech, a medical historian at the Medical University of Vienna and author of the new paper. “I think we also have to part ways with the idea that an eponym is an unmitigated honor of the person. It is simply a historical acknowledgement that can be, in some cases, troubling or problematic.”

Revising history:

Asperger syndrome officially entered the medical lexicon in 1981 when British psychiatrist Lorna Wing found Asperger’s 1944 thesis and popularized his work.

In 1992, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) included the syndrome and, two years later, the DSM did the same.

The term is still listed in the ICD-10, that manual’s current version. But the ICD-11, expected to debut in May, will subsume the syndrome into the autism diagnosis, just as the DSM-5 does.

Yet the term is still widely used to refer to someone on the milder end of the autism spectrum.

Asperger was never a member of the Nazi Party. And for decades, books and academic articles portrayed him as a benevolent figure who saved children with autism from the killing centers.

But in 2005, a medical historian named Michael Hubenstorf revealed that Asperger had had a close relationship with the prominent Nazi physician Franz Hamburger. In the 2015 book “Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity,” journalist Steve Silberman also connected Asperger to Hamburger, but he didn’t find a link to Nazi eugenics.

It wasn’t until historians dug up Asperger’s clinical records that the truth came to light.

New revelations:

The children’s clinic where Asperger worked was bombed by Allied troops, and for decades many people believed the clinical records had been destroyed.

In 2009, Czech was asked to speak at a 2010 symposium commemorating Asperger’s death. That inspired him to start digging into the government archives in Vienna for details about the pediatrician — where he discovered the well-preserved clinical records.

Czech found a Nazi Party file that vouched for Asperger’s loyalty even though he was not a member. He also found talks Asperger gave, as well as his medical case files and notes.

Two years later, historian Edith Sheffer visited the same Vienna archives. Sheffer has a son with autism and had long been curious about Asperger, who she had thought had a “heroic” reputation.

“From the very first file I found in the archives, I saw that he was implicated in the Nazi program that actually killed disabled children,” says Sheffer, senior fellow at the University of California, Berkeley’s Institute for European Studies. She is the author of the new book, which is expected to be released in May.

Asperger described the behavior of children with autism as being in opposition to Nazi Party values. For instance, a typical child interacts with others as an “integrated member of his community,” he wrote, but one with autism follows his own interests “without considering restrictions or prescriptions imposed from outside.”

Asperger’s clinical files describe children with disabilities and psychiatric conditions in far more negative terms than his colleagues did. For instance, Am Spiegelgrund physicians described a boy named Leo as “very well developed in every respect.” Asperger described him as a “very difficult, psychopathic boy of a kind which is not frequent among small children.”

Asperger’s closest colleagues and mentors were the architects of Am Spiegelgrund’s eugenics program. “He was traveling at the highest echelons of the killing system, and so I really see him as more than just a passive follower,” Sheffer says.

Czech found evidence suggesting Asperger personally transferred at least two children to Am Spiegelgrund and served on a committee that referred dozens of others; the children died there. There is no evidence that Asperger saved children from the clinic.

“Could he have sent more children to Spiegelgrund? Yes, of course,” says Czech. “But did he refrain in all cases? No.”

Greater organism:

The archives also reveal an arc in Asperger’s descriptions of children in his clinic. In 1937, before World War II, Asperger was circumspect in classifying children. But within months of Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938, he began describing children with autism as a “well-characterized group of children,” Sheffer says. Within three years, he began calling them “abnormal children.” And by 1944, he described them as outside “the greater organism” of the Nazi ideal.

“Why did he adopt the writing style that he did? I think because he was up for promotion,” Sheffer says of his evolving approach.

She says Asperger’s career soared during the war years. As his Jewish colleagues were removed from their positions, he rose through the ranks.

After the war, however, he described himself in interviews as a resister of Nazi ideology and called the euthanasia program “totally inhuman,” according to Sheffer.

As disturbing as the revelations are, they are an important part of autism research, experts say.

Information on Asperger’s life was “scant” in the 1990s, when Ami Klin, director of the Marcus Autism Center in Atlanta, tried to track it down. “There was no historical scholarship invested in that,” he says. Klin is on the board of Molecular Autism.

Now that the details are out, however, people are divided on the appropriate way forward.

Even the two historians disagree: Unlike Czech, Sheffer says people should stop using the word ‘Asperger.’ Ending the term’s usage would “honor the children killed in his name as well as those still labeled with it,” she wrote in The New York Times.

Some people who received a diagnosis of Asperger syndrome say it’s time to bury the term, but urge caution. “I would be very upset if there was some sort of consensus that the findings themselves were tainted and needed to be set aside because of the nature of the person who contributed them,” says Phil Schwarz, a software engineer in Massachusetts who is on the spectrum.

At the very least, others say, keeping the name may help us remember the lessons of this dark past.

References:

- Czech H. Mol. Autism Epub ahead of print (2018) Abstract

Syndication

This article was republished in Science.

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt