New diagnostic criteria may abate autism prevalence

About one in five children who appeared to have autism in 2006 and 2008 would lose that classification with the diagnostic criteria for autism released last year, according to a study published yesterday in JAMA Psychiatry.

About one in five children who appeared to have autism in 2006 and 2008 would lose that classification with the diagnostic criteria for autism released last year, according to a study published yesterday in JAMA Psychiatry1.

The study is the largest yet to look at the impact of the DSM-5, the newest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, on autism diagnoses. It suggests that as many experts predicted before the guidelines’ release, the new standards will lower autism’s prevalence.

The most controversial change for autism in the DSM-5 is the newly defined ‘autism spectrum disorder,’ which subsumes Asperger syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified. Many experts (and parents) publicly worried that the new category might exclude high-functioning children with autism, preventing them from receiving services.

Studies on the topic have yielded widely varying results, finding that anywhere from 9 to 54 percent of people with autism would lose their diagnosis2, 3. These studies each relied on only a few clinical sites, however. The new study assesses the guidelines’ effect much more broadly.

“We were just really curious about what impact it might have in a population-based setting where we might examine prevalence,” says lead researcher Matthew Maenner, epidemic intelligence service officer at the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

Maenner and his colleagues found that when they reassessed records from previous years, the 2006 prevalence of autism drops to about 0.7 percent from 0.9 percent using DSM-IV criteria and the 2008 prevalence to 1 percent from 1.13 percent.

In terms of this population-wide prevalence, the changes are small, notes Eric Fombonne, director of the Autism Research Center at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, who was not involved in the study.

“At the end of the day, the concern that people had about the major impact of the DSM-5 is not borne out by these data,” Fombonne says. “It shows a relatively modest impact of the change, and not one over which everybody should get up in arms about.”

Wide view:

The study uses existing CDC data from prevalence studies conducted in 2006 and 2008. The population-wide approach relies on both medical and special education records for all 8-year-old children from 14 representative states.

This is an “obvious strength” of the study, says William Mandy, senior lecturer in clinical psychology at University College London, who was not involved in the work. “The results are more likely to be generalizable beyond a particular clinic or service,” he says.

Overall, Maenner and his colleagues examined the records of 6,577 children. Some of these children did not have an existing autism diagnosis but met DSM-IV criteria based on notes in their records. Of the total, 5,339, or about 80 percent, meet the DSM-5 criteria for autism.

The researchers also looked at another 1,020 children who met DSM-IV autism criteria but who were ultimately not considered to have the disorder — usually because they were a better fit for a different category. Of these children, about 300 received an autism diagnosis using the DSM-5. “The number of potential new cases gained under the DSM-5 is quite small,” says Maenner.

The concern that people had about the major impact of the DSM-5 is not borne out by these data.

Among the 20 percent who lost their diagnosis, the most common reason for the change is a lack of “deficits in non-verbal communication used for social interaction.” This is one of three ‘social communication’ criteria, all of which are required under the DSM-5.

The study suffers from the same limitation as other retrospective analyses of the DSM-5, however: Individuals assessed in previous years may be missing certain DSM-5 criteria because those traits were not considered worth noting at the time.

“In 2008, the people doing evaluations of children were not even aware that the DSM-5 was on the horizon,” says Maenner. “They might [now] be more inclined to document features that receive greater emphasis in the new criteria.”

This possibility is borne out by the fact that children who had received an autism diagnosis from a professional were more likely (85 percent) to keep their autism diagnosis than those assigned one based on their medical and education records (70 percent).

The findings suggest that clinicians should focus on developing standardized methods to assess autism so that they don’t miss any key symptoms, says Catherine Lord, director of the Institute for Brain Development at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City, who was not involved in the study.

“It’s not that the prevalence rate is going down; it’s just that in these somewhat systematic assessments of autism, there are probably kids being missed,” she says. “How do we get clinicians or school systems to pay more attention to what autism is?”

New labels:

Another flaw of the study is that the researchers used different methods to estimate prevalence under the DSM-5 criteria than they had with the DSM-IV, notes Young-Shin Kim, associate professor at the Yale Child Study Center in New Haven. “It’s like comparing apples to oranges,” she says. “This brings a huge bias to the prevalence results.”

Most significantly, Kim says, clinicians had reviewed each record used for the original prevalence estimates, considering autism and other possible diagnoses. This extra step is missing in the new estimates, she says. Kim is set to publish similar findings on the effects of DSM-5 criteria on Korean prevalence estimates, but hers rely on thorough clinical reanalysis of each case, she says.

Kim’s study also considers whether children who lose their diagnosis under the DSM-5 would receive a different label. For example, a new category called Social Communication Disorder (SCD) is intended for children who have the social deficits characteristic of autism but who do not have repetitive behaviors or restricted interests.

“The kids lost on the DSM-5 might well fall into SCD now,” says Fombonne. “If you add the SCD next to the DSM-5, maybe you would get roughly the same numbers at the end of the day.”

One of the concerns about the introduction of SCD has been whether children assigned to this new diagnosis would have access to the same services as do children with autism. But the new study suggests that loss of services may not be a significant concern for children who seek thorough clinical diagnoses.

“My take-home on it is that this study certainly doesn’t clinch the argument that DSM-5 lacks sensitivity,” says Mandy. “The studies that tend to use very careful and detailed measurement of autism symptoms tend to find that DSM-5 criteria are rather more sensitive.”

References:

1: Maenner M.J. et al. JAMA Psychiatry Epub ahead of print (2014) Abstract

2: Mattila M. L. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 50, 583-592 (2011) PubMed

3: Huerta M. et al. Am J. Psychiatry 169, 1056–1064 (2012) PubMed

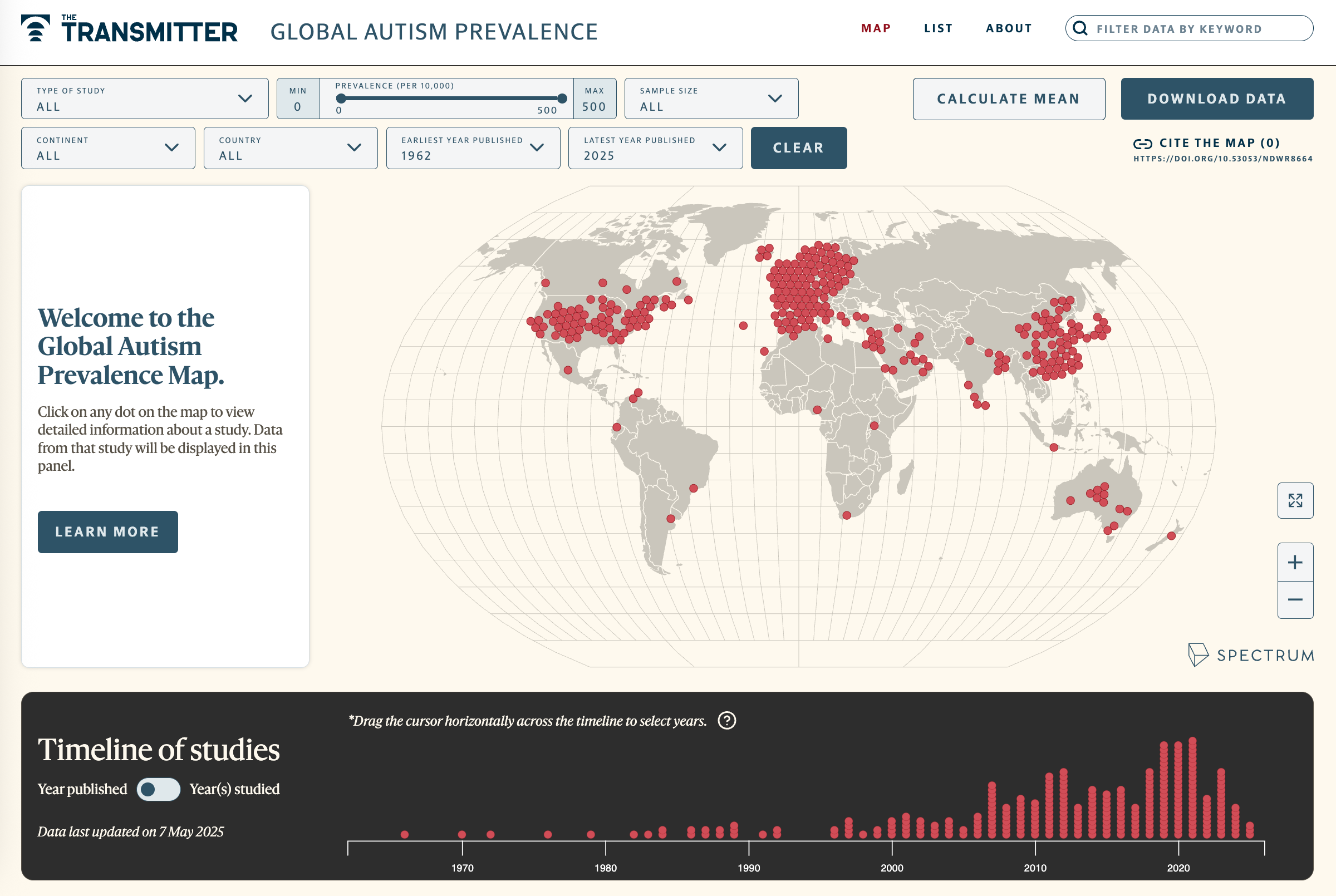

Visit our Global Autism Prevalence Map

Explore more >

Recommended reading

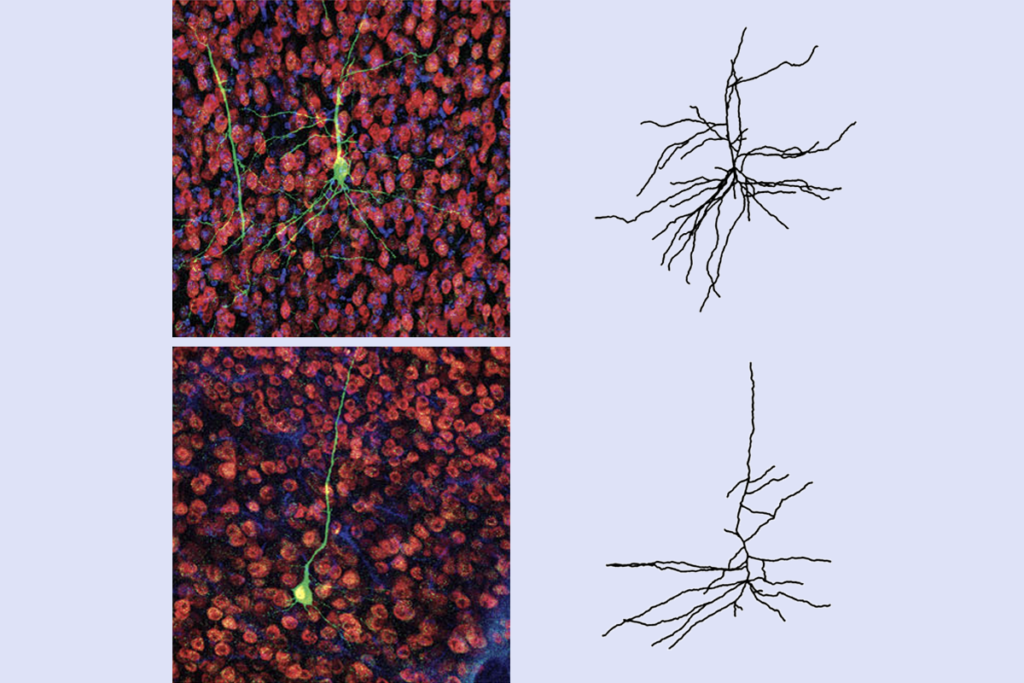

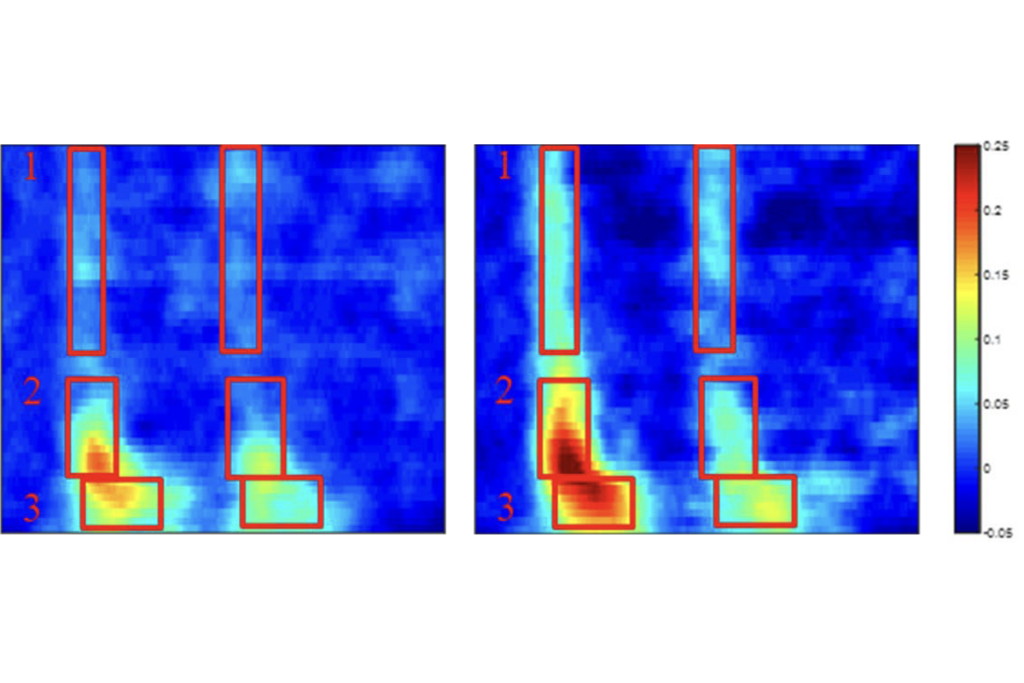

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Home makeover helps rats better express themselves: Q&A with Raven Hickson and Peter Kind

Explore more from The Transmitter

New findings on Phelan-McDermid syndrome; and more