New autism map points to diagnostic deserts in United States

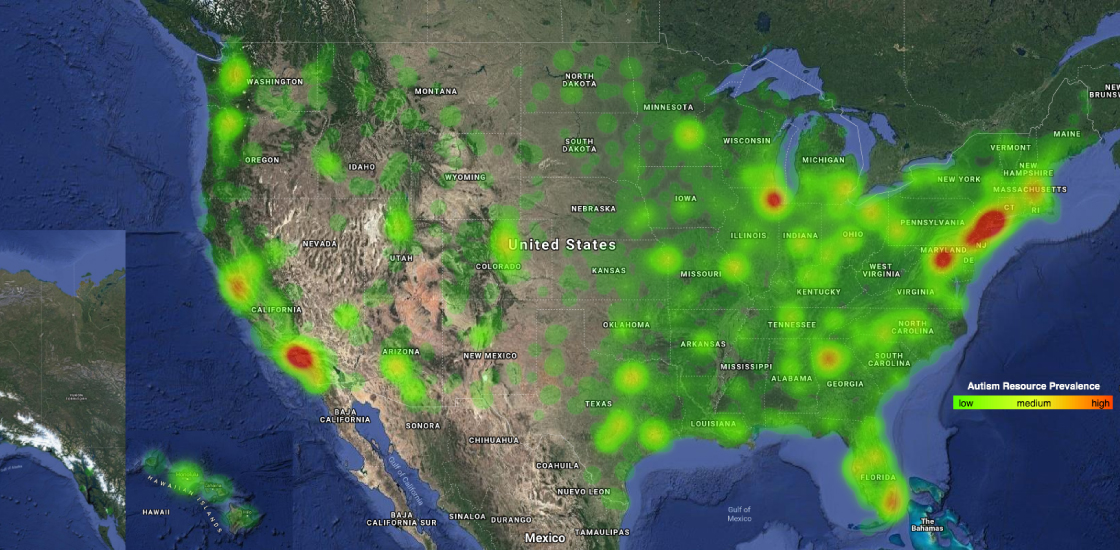

Most regions in the United States do not have an autism diagnostic center or specialist.

More than 80 percent of counties in the United States do not have diagnostic centers for autism, according to a new database1. And across the country, autistic people live, on average, about 22 miles from a diagnostic center.

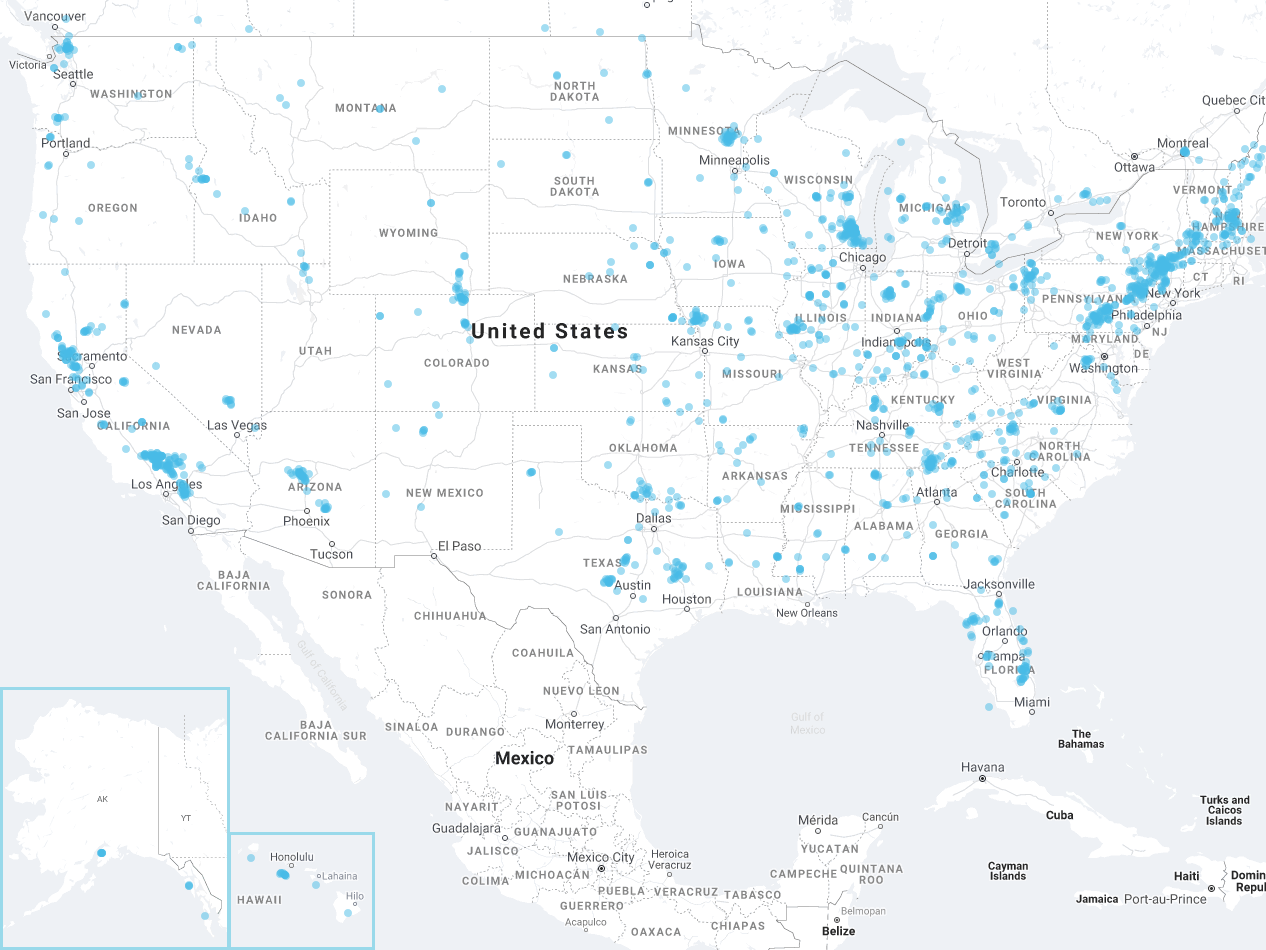

The findings are from an online database called GapMap, which displays about 28,000 resources, such as autism therapy clinics, educational supports and diagnostic centers. Autistic people in the U.S. live 11 miles, on average, from the nearest such resource, according to the database.

These numbers show that there are significant barriers to getting an autism diagnosis. “We need to do something about it,” says lead researcher Dennis Wall, associate professor of pediatrics and biomedical data science at Stanford University in California, such as training more developmental specialists and performing diagnostic evaluations via video or other technology. (Wall has led studies of such remote evaluations, which have been criticized by some experts.) GapMap may help experts identify regions most in need of specific autism services, he says.

The study is a useful step toward identifying voids in autism resources, says Walter Zahorodny, associate professor of pediatrics at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, who was not involved in the research. He cautions, however, that it relies on assumptions about where autistic people live based on population density rather than on data of autism prevalence.

“It’s limited, for sure. But it doesn’t take away from the fact that they are attempting a new approach and a new model,” Zahorodny says.

Diagnostic deserts:

Wall and his colleagues mined three online databases of autism resources — from the advocacy group Autism Speaks and the nonprofits Parents Helping Parents and the Autism Society. Using these and other data gathered from an online database called Google Places, the researchers created an interactive map of autism resources.

The map shows an abundance of specialists and other resources near East Coast cities, from Boston to Washington, D.C., and near Chicago and Los Angeles. By contrast, large swaths of the Midwest and West have few autism resources.

West Virginia, Kentucky and Maine have the fewest resources relative to their population, and Montana, Connecticut, Colorado and Rhode Island have the most. Researchers reported the findings in July in the Journal of Internet Medical Research.

“This is a really easy and nice way to visualize what’s happening,” says Sarabeth Broder-Fingert, assistant professor of pediatrics at Boston University. “You can reference this, and people can see with their own eyes very clearly where the resources are and where there are probably gaps.”

The researchers grouped the resources into seven categories, including therapy, diagnosis and education. Therapy is the most prevalent, accounting for about 41 percent of autism resources. Diagnostic centers are scarce, at 9 percent.

The researchers then used 2016 census data and a national autism prevalence of 1 in every 59 people — the latest official figure — to estimate that about 5.5 million autistic people live in more than 3,000 U.S. counties. They mapped points representing these autistic people in each county, based on the county’s population density. However, they did not account for the fact that autism prevalence varies by U.S. region.

Quality control:

Their simulation shows that the availability of resources varies greatly across the country. Autistic people in Alaska need to travel about 63 miles to the closest resource, for example, whereas those in Nevada must travel more than 30 miles and those in New Jersey just 2 miles.

“Our goal is to get a general idea of the state of things; I think we achieved that,” Wall says. “[The work] really highlights the importance of replacing simulated data with real data.”

The researchers plan to set up a portal that would allow people with autism to report their location, enabling the team to improve the map’s accuracy. They also plan to update the map with newly identified service providers.

The team did not verify that the clinics and providers listed offer evidence-based care, but they did confirm that the services listed are operational. However, the map is missing certain services, such as school systems that identify children eligible for autism treatments, says Catherine Lord, distinguished professor in residence of psychiatry and education at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Trying to do this is a noble cause, but I just think it’s hard,” she says.

Wall and his colleagues have also created a map of autism resources in Bangladesh, where his team is testing a video-based diagnostic tool.

References:

- Ning M. et al. J. Med. Internet Res. 21, e13094 (2019) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Psychedelics research in rodents has a behavior problem

Can neuroscientists decode memories solely from a map of synaptic connections?