Mutation tied to autism deprives male mice of their sleep

A DNA deletion linked to autism causes male mice, but not females, to have trouble falling asleep.

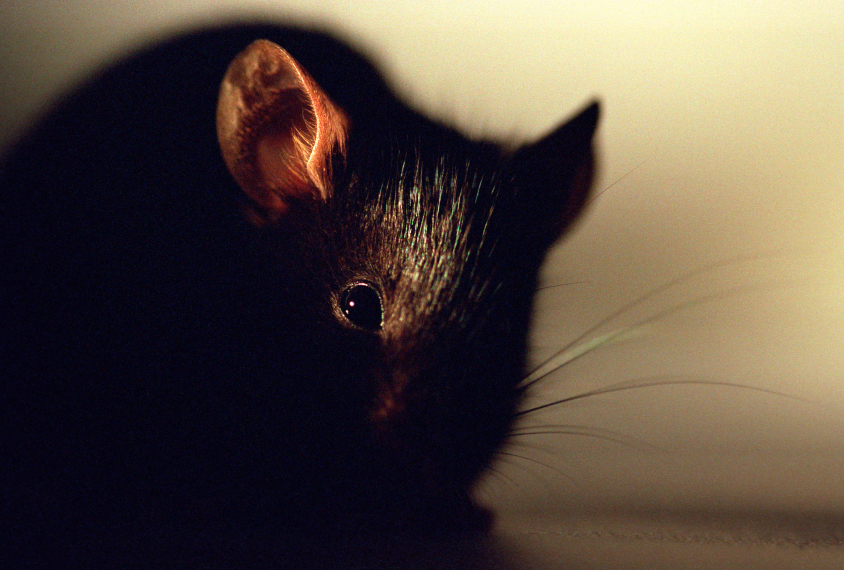

Male mice with a DNA deletion linked to autism have trouble falling asleep, according to a new study1. Female mice with the same mutation fare well with sleep. All mice with the mutation are hyperactive.

Researchers could use the mice to test treatments for sleep disturbances and hyperactivity — problems that often accompany autism, says lead researcher Ted Abel, professor of biology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The mice could also offer clues to how a genetic mutation has different effects in males and females, Abel says.

The mice are missing a stretch of DNA on chromosome 16 called 16p11.2. People with this deletion have a range of features, including intellectual disability and language problems. Roughly one in four children with 16p11.2 deletions have autism and one in five have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)2.

The new work, which appeared 14 October in Autism Research, meshes with anecdotal reports of sleep problems among children with a 16p11.2 deletion. Efforts to rigorously confirm the reports are underway, says Ellen Hanson, director of the Neurodevelopmental Disorders Phenotyping Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who was not involved in the new study.

“We need to do further work with this, using the mouse model as well as measuring our children directly, since sleep time and quality are so important,” says Hanson, who studies a group of children with 16p11.2 deletions.

Sleep sensors:

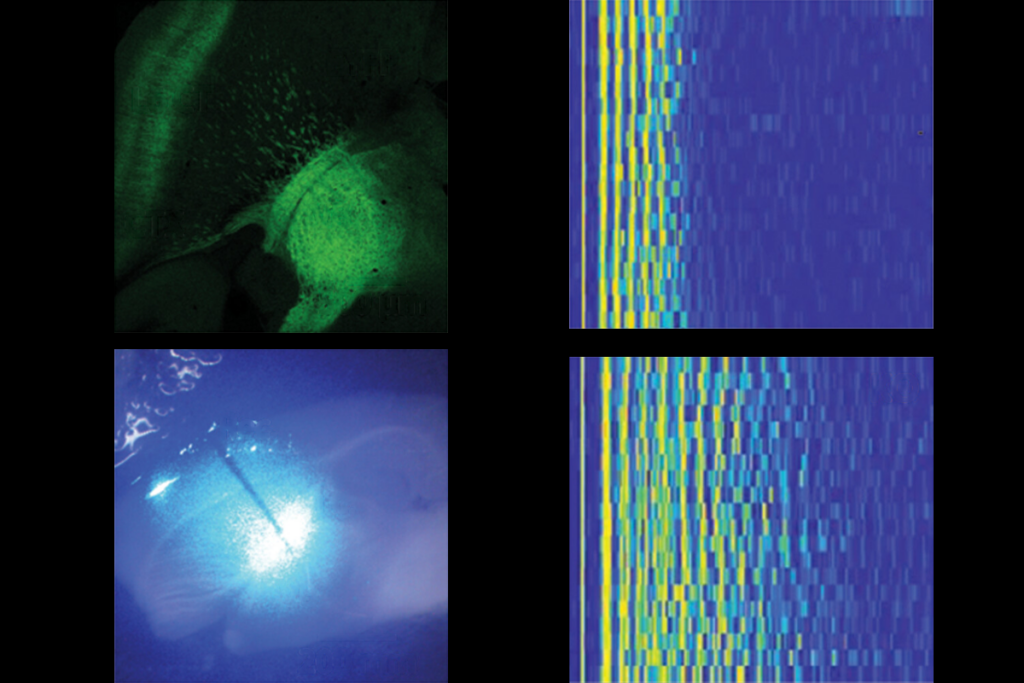

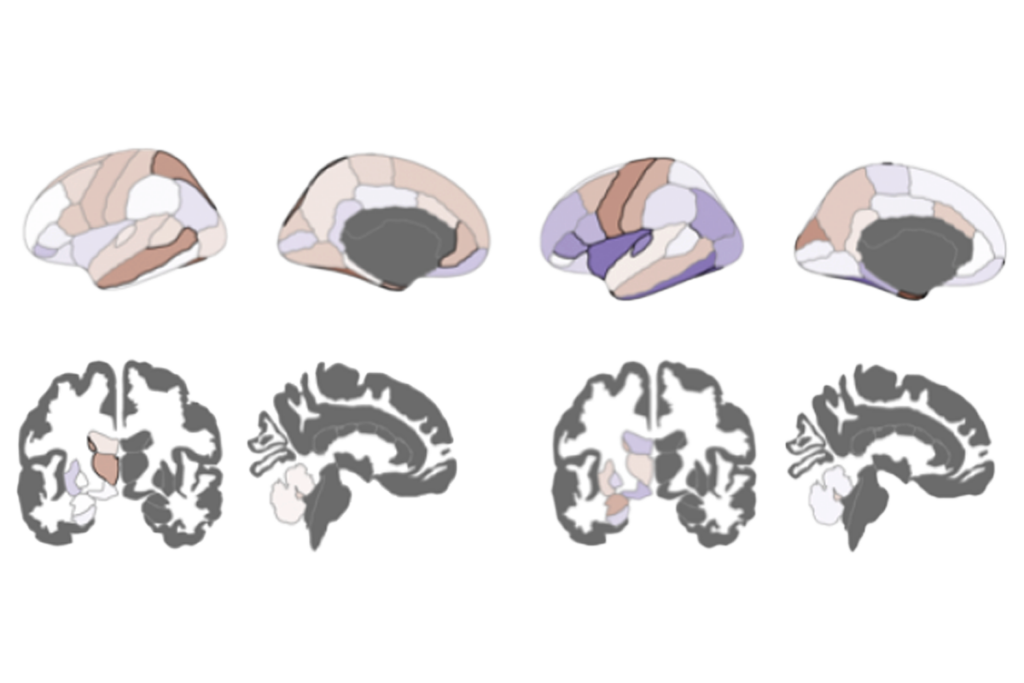

Researchers have engineered three strains of mice that carry slightly different versions of deletions in the 16p11.2 region (see graphic below). All three strains show signs of hyperactivity.

The new study bolsters this finding. The researchers monitored the mice in a cage rigged with infrared sensors that automatically measure motion around the clock. (Mice are active at night and tend to sleep during the day.)

Both male and female mice with the deletion are significantly more active at night than controls are. They break the beams of infrared light roughly four times as often as controls do. “To have a behavior that changes four-fold, which is what the male activity does, is pretty amazing,” Abel says.

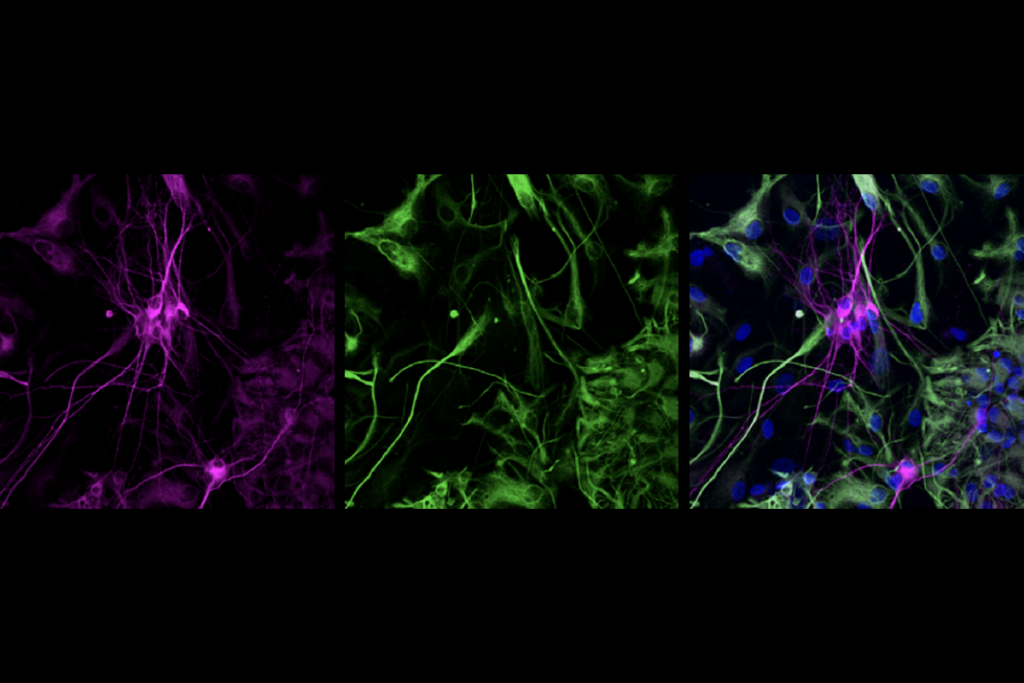

The researchers also measured sleep duration and quality by implanting electrodes in the brains of the mice. The equivalent technique in people, called polysomnography, uses caps covered in electrodes to detect brain activity related to sleep.

by Lucy Reading-Ikkanda

Male mice with the 16p11.2 deletion are awake slightly longer than male controls are during the second half of the day. But the animals have normal stretches of deep sleep, called rapid eye movement sleep. This observation suggests that the mice experience extended periods of wakefulness rather than poor sleep quality, Abel says.

Female mice with a 16p11.2 deletion show typical sleep patterns, supporting the theory that mutations tied to autism have more severe effects in males than in females. Problems with sleep may exacerbate autism features, Hanson says.

Scientists could use the mice to explore brain alterations underlying specific behaviors. Changes shared by female and male mice may underlie hyperactivity, whereas those specific to males could contribute to sleep problems, Abel says.

The researchers have also made mice missing 16p11.2 in neurons that make up certain brain circuits. They can use these mice to assess whether hyperactivity or sleep problems stem from specific brain circuits.

The researchers also plan to use the automated cage to track treatments for sleep and hyperactivity over time.

References:

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Sensory gatekeeper drives seizures, autism-like behaviors in mouse model

Structural brain changes in a mouse model of ATR-X syndrome; and more