A

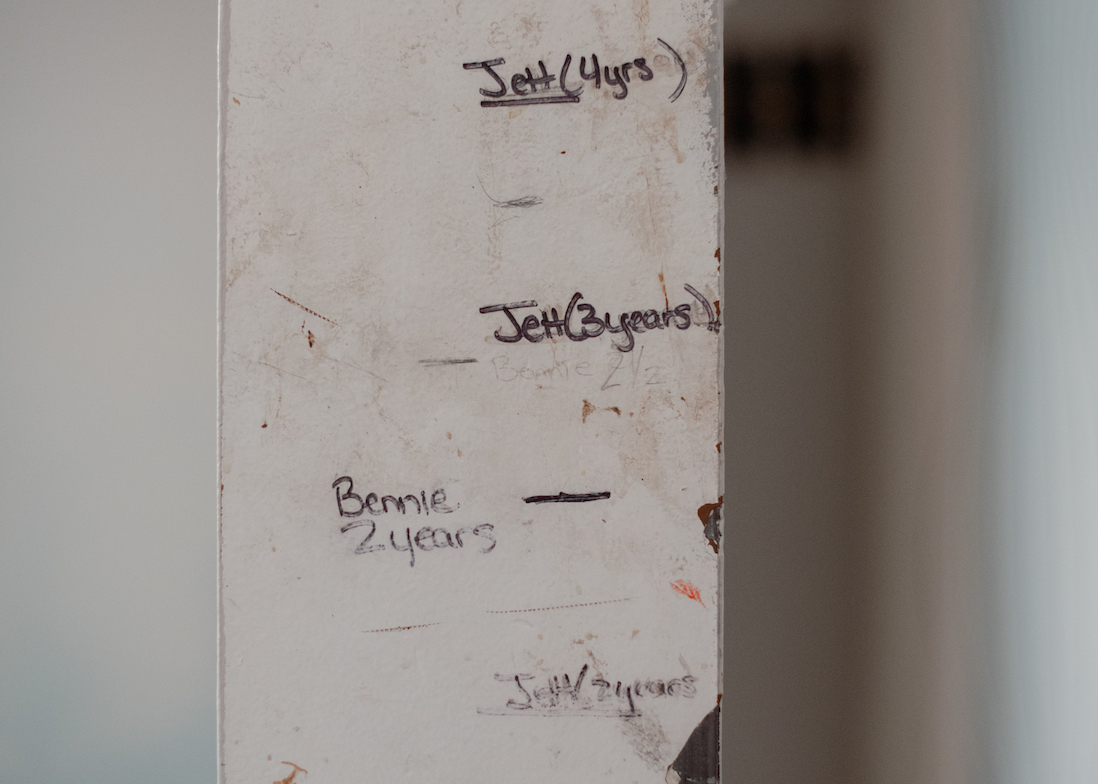

fter their son Jett was diagnosed with autism, Sarah Harris and James Shilling found the local care wanting in West Virginia, where they live. They faced long waitlists for the standard autism therapy, applied behavior analysis (ABA), and local schools were either too expensive or lacked programs appropriate for their son. Harris and Shilling envied the options they found in the neighboring state of Ohio, such as ABA-centered curricula designed for children with learning and sensory differences. “I got really frustrated that we couldn’t do something like that,” Harris says. They wanted to move — but felt they could not afford to do so. Shilling’s unionized job as a truck driver was not easily transferable, and the family feared losing their health insurance.David and Michelle Lane, who live in Kentucky, were also eyeing better care across state lines. When their son Aaron, who has autism, became aggressive as a pre-teenager, nothing they tried seemed to help. Appropriate therapy and schooling seemed elusive where they lived, Michelle recalls. So by the time Aaron was 17, the family felt they had exhausted all local options, and they decided to move. “We looked all over the whole country,” David says. In the end, they decided on Boston, Massachusetts, after friends with a daughter on the spectrum raved about the great schools there.

No one knows exactly how many families move, or want to move, for better autism services in the United States, but some evidence suggests that the desire to do so is common. Unpublished findings from a 2004 survey of 969 caregivers of people with autism suggest that about 1 in 5 moved to get higher quality services, according to David Mandell, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Local U.S. autism organizations, including the Autism Society of Colorado and AutismUp in Rochester, New York, say that just about every week they hear from a family wanting to move to another state in search of superior care. And autism forums on sites such as BabyCenter, Facebook and Reddit are rife with questions from parents about autism-friendly states.

That so many autism families are willing to uproot themselves reflects an endemic problem in the U.S.: large disparities between states in access to diagnostic services and treatments for autism, schooling and the cost of care, according to several reports documenting these issues. These disparities lead to inequities between people who can afford to move for better options and those who cannot, says Dennis Wall, a biomedical data scientist at Stanford University in California. But even for the more fortunate families, the differences create a ‘Sophie’s choice’: Move in search of better options for their children but lose the stability of home, or stay put and keep some supports but relinquish the possibility of others.

Moving often has serious downsides, including cost, distance from family support systems, and life disruptions of the type autistic people find especially difficult. “I can only imagine that for a child for whom routines are comforting and helpful, which is all children but maybe especially children with autism, that moves can be incredibly psychologically disruptive,” Mandell says. In addition, relocation is not necessarily a panacea. No state is perfect; there are gaps in care everywhere, and places that are great for young children may not be optimal for older ones.

Experts say that the situation for these families would be vastly improved if autism diagnostic services and treatments were easily accessible across states and counties and were reimbursed equally. “It breaks my heart and makes me angry that we as a society have decided that these are not services that we value enough, and that these are not people we value enough, to make autism services available where people are,” Mandell says.