Mouse monopoly

There are a host of problems with laboratory rodents that scientists rarely talk about, argues a fascinating series of articles in Slate magazine.

-

Slate

Since the first mouse model of autism debuted in 2007, I’ve heard lots of debate over how, and even whether, the critters recapitulate the disorder.

Does their preference for objects over other mice count as a social deficit? Do their abnormal high-pitched squeaks reflect communication problems? How much of a problem is it that the same genetic glitch produces different behaviors in different strains of mice?

But there are more fundamental problems with laboratory rodents that scientists rarely talk about, argues a fascinating series of articles published last week in Slate magazine. Mouse models of autism have had a fantastic run, unraveling key biological pathways involved in the disorder. But I think it would be productive for researchers to begin thinking about breaking up the mouse monopoly.

For example, one big problem is that to keep mice cheap and standardized, they are inbred and raised without exposure to germs or exercise. These lazy, fat animals could have major metabolic, immune or attentional abnormalities that not only don’t mimic the disease they’re supposed to model, but may affect the results of various tests.

Another issue is that different kinds of mice have unique quirks. The most popular strain of lab mouse, dubbed Black-6, for example, is extremely sensitive to temperature and pain, has hearing loss with age, and tends to pull hair off of other mice in its cage.

Perhaps most important, because of inherent differences in anatomy and biology, rodents also don’t always react to diseases, or treatments, the same way people do.

All of these factors, the articles argue, are preventing researchers from developing effective new drugs.

I’m sure many autism researchers would take issue with this line of thinking. But one point is indisputable: Mice and rats overwhelmingly dominate the research enterprise.

A 2008 European report found that these rodents make up 77 percent of all vertebrates used in scientific research. Another survey of neuroscience papers published from 2000 to 2004 found that 45 percent used rodents, 30 percent relied on humans, 8 percent on invertebrates, and the remaining focused on other species.

Overall, Slate estimates that scientists worldwide are using some 88 million rats and mice each year.

There are good reasons for this, of course, including the fact that it’s relatively easy to manipulate rodent genes. In just the past few years, the autism field has produced more than two dozen mouse models and seven rat models, each lacking a gene or chromosomal segment linked to the disorder.

But when it comes to testing drug candidates, rodents fail often enough to give pharmaceutical companies pause.

When researchers announced the new rat models last week, several scientists told me that the field should go back to the comparative biology that naturalists were doing more than a century ago.

If researchers make models of autism using several different species — say, mouse, rat, fly, fish, bird and worm — and all of them have interesting defects, that collection of models would have more human relevance than just one oddly behaving mouse.

Recommended reading

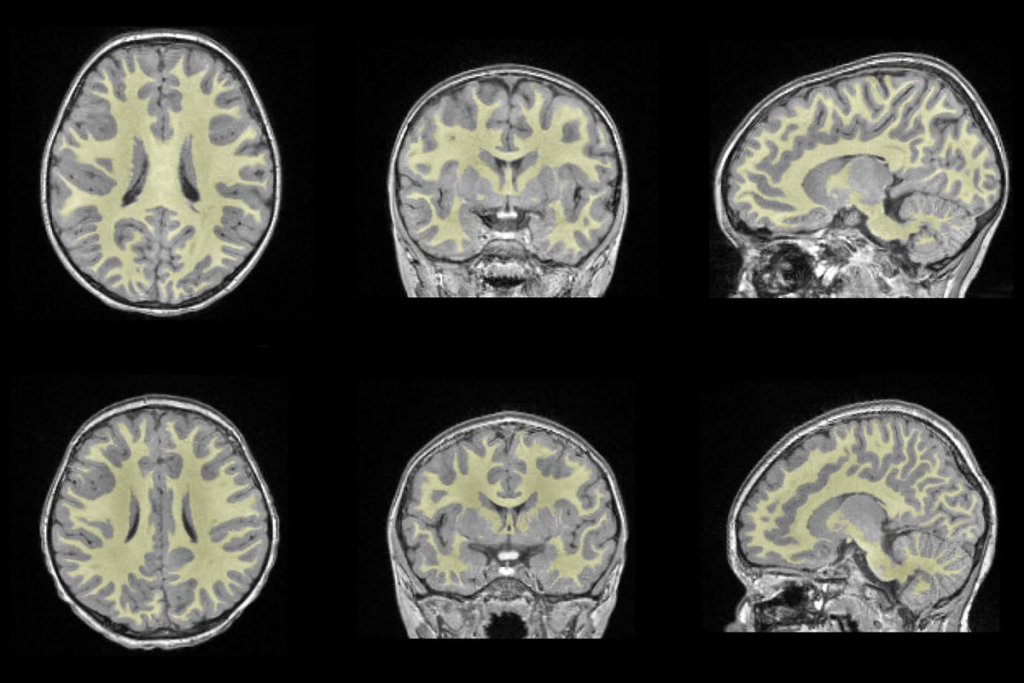

White-matter changes; lipids and neuronal migration; dementia

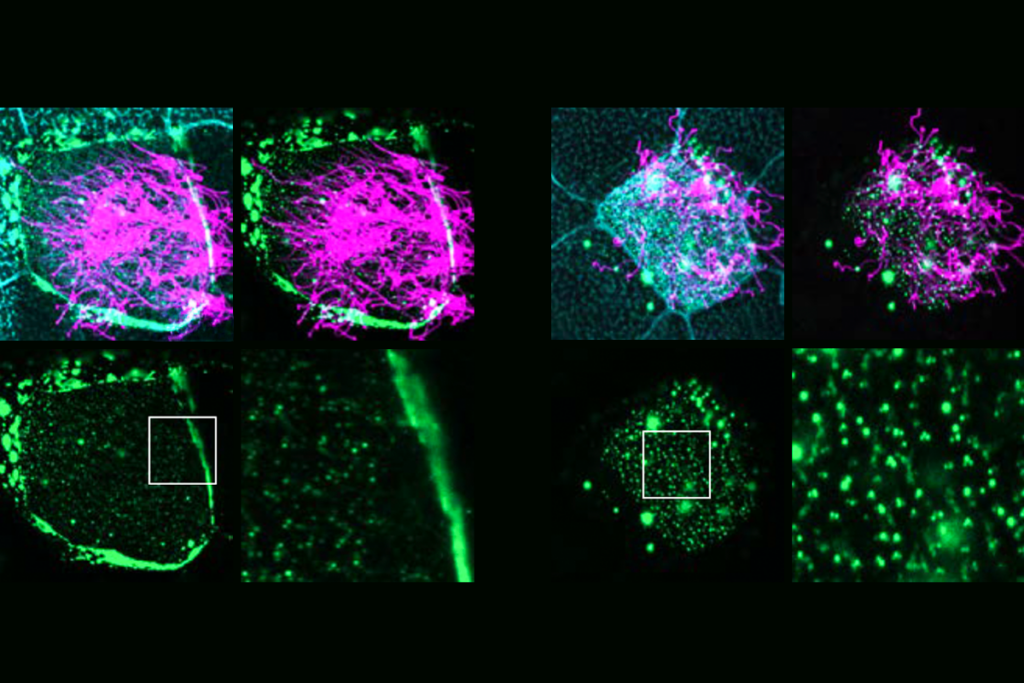

Many autism-linked proteins influence hair-like cilia on human brain cells

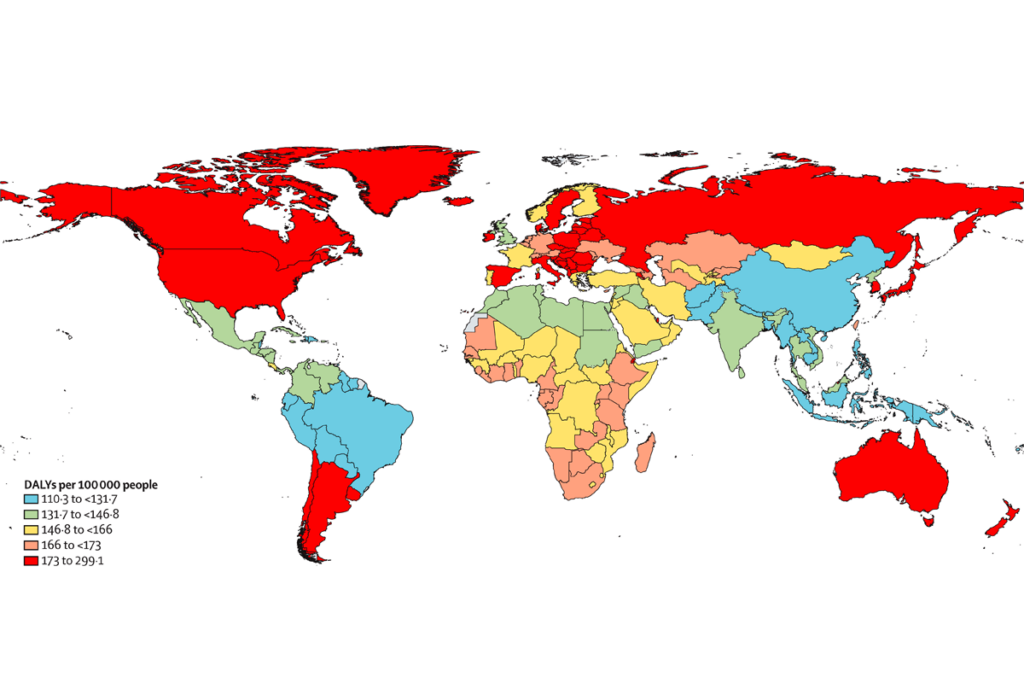

Functional connectivity; ASDQ screen; health burden of autism

Explore more from The Transmitter

David Krakauer reflects on the foundations and future of complexity science

Fleeting sleep interruptions may help brain reset