A new molecular tool enables researchers to create mosaic mutations in a mouse model and then accurately identify which cells are affected.

Mosaic mutations — those that appear in only some of the body’s cells — contribute to about 4 percent of autism cases. The mutations that underlie Rett syndrome, tuberous sclerosis complex and fragile X syndrome, which are often characterized by autism traits, can also occur in a mosaic pattern.

Scientists typically mimic mosaic mutations in mice by using Cre recombinase, an enzyme that cuts DNA between two specific sequences. They can deliver low levels of Cre or a Cre-activating drug to induce mutations in a subset of cells engineered to express a fluorescent protein in Cre’s presence. But such low levels of Cre do not consistently induce mutations, nor the expression of the fluorescent protein.

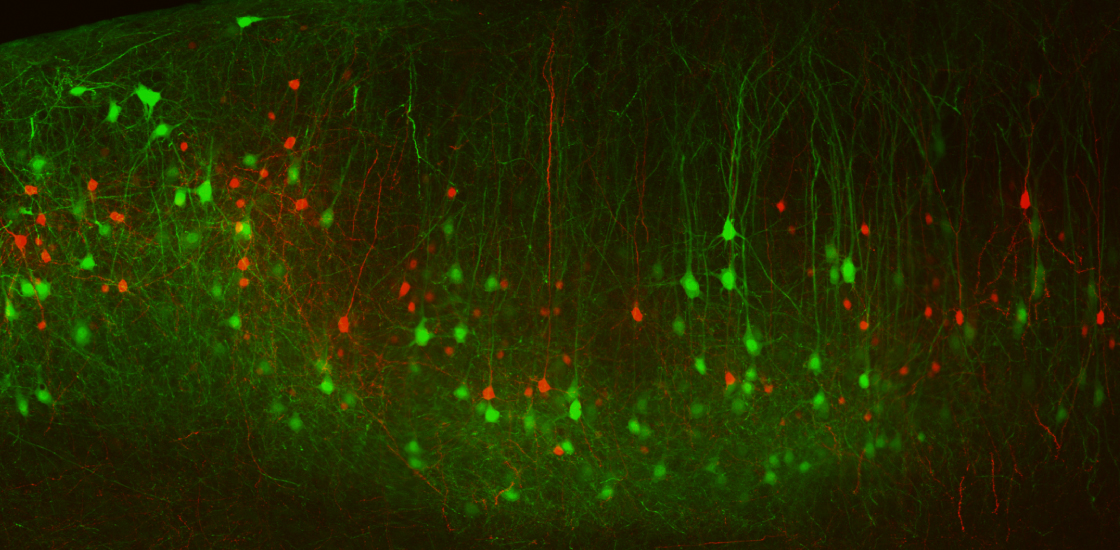

In the new method, researchers amplify Cre expression to more reliably introduce and detect mosaic mutations. The approach uses a novel DNA loop, or plasmid, called Beatrix. This ‘reporter’ plasmid expresses a red protein in the absence of Cre, but a green one, plus additional Cre, in its presence.

True colors:

The team tested the approach in lab-grown cells, exposing one set to a high concentration of Beatrix and another to a conventional reporter plasmid that produces the same red and green proteins but doesn’t amplify Cre. They also tested the approach in mice, injecting the plasmids into the animals’ brains in utero.

The conventional reporter prompts some cells to express both red and green proteins, the researchers reported in December in Nature Communications. With Beatrix, however, cells express almost exclusively either green or red proteins. In mice, less than 0.1 percent of neurons express both proteins, according to two-photon microscope images of their brains taken 30 days after birth.

The new reporter plasmid is also 10 times more sensitive to low Cre concentrations than the conventional reporter is. This heightened sensitivity means that scientists can alter the concentration of the Cre plasmid to adjust the number of cells that carry a mutation, the researchers say.

In another experiment, the team used Beatrix to delete a portion of the autism-linked gene PTEN in a subset of neurons in mice. They then stained cells expressing the PTEN protein with fluorescent antibodies and compared the results with those suggested by Beatrix.

The novel reporter accurately identifies the cells with mutations in PTEN, the researchers reported. All the cells that expressed red proteins expressed PTEN, whereas all the cells that expressed green proteins did not.

Examining differences between red and green cells, the researchers also found that neurons lacking PTEN are larger than those that express the gene, a finding consistent with previous studies in mice. In addition, analyzing brain activity in mosaic mice revealed seizure-like bursts similar to those seen in some people with PTEN mosaicism, who often have epilepsy.

Beatrix could help shed light on the role of mosaic mutations in neurodevelopmental conditions, the researchers say. It could also be used to study the differences between cells with and without mutations in autism-linked genes in the same animal.