Molecular mechanisms: Response to sound could diagnose autism

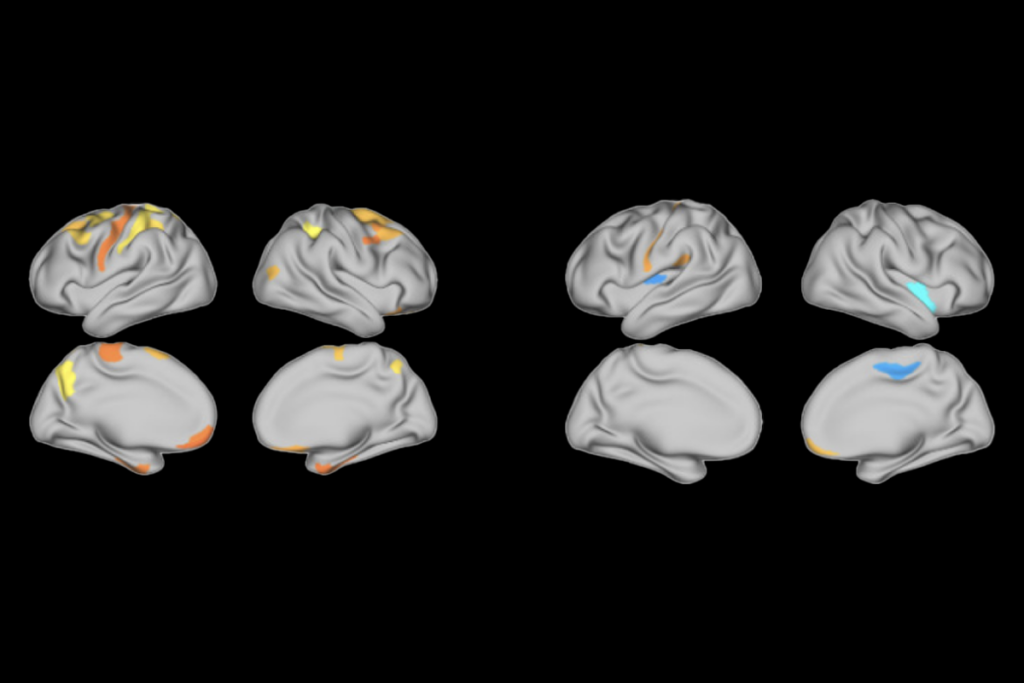

A delayed response to unexpected changes in sound frequency is a marker for language impairment and autism, according to a study published in March in Biological Psychiatry.

A delayed response to unexpected changes in sound frequency is a marker for language impairment and autism, according to a study published in March in Biological Psychiatry.

Electroencephalography (EEG) detects the pattern of electrical activity conducted by neurons in the brain, and magnetoencephalography (MEG) measures related fluctuations in the magnetic field.

These tests, although expensive, are non-invasive and can be used on young, awake children, making them a promising technique for early biomarkers of autism.

When healthy controls hear an unexpected sound, there is a spike in MEG activity — termed a mismatch field — that can be used as a measure of when and how strongly their brain detects this change.

In the new study, researchers compared how long it takes children who have both autism and language delay to respond to a ‘divergent’ sound — a different syllable or tone — after a repeated ‘expected’ sound, compared with children with autism who have no language delay and typical controls.

The experiments used either an electronic recording that simulates a human voice switching from the syllable ‘a’ to ‘u,’ or two frequencies of tone — 300 Hz and 700 Hz — that correspond to the tones of the syllables.

The 18 children, aged 6 to 15 years, who have both autism and language impairment take 50 milliseconds longer to detect tone and syllable changes compared with 27 controls. The 33 children who have autism but no language impairment have responses somewhere in between the two groups.

Although it seems short, 50 milliseconds is “a long time in the lifetime of a syllable” — which averages about 250 milliseconds — and could lead to problems in following along with speech, says Timothy Roberts, vice chair of research in radiology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and lead investigator on the study.

All three groups responded in the same way to both tones and syllables, suggesting that language delay in autism could be the result of defects in sound processing.

The researchers are exploring whether the delay is specific to autism-related language impairment or is also present in typically developing children diagnosed with language defects.

Recommended reading

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

‘Tour de force’ study flags fount of interneurons in human brain

FDA website no longer warns against bogus autism therapies, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Michael Shadlen explains how theory of mind ushers nonconscious thoughts into consciousness

‘Peer review is our strength’: Q&A with Walter Koroshetz, former NINDS director