Changes in gene regulation and expression precede alterations in neuronal function and behavior in mice lacking MECP2, the gene implicated in Rett syndrome, according to a new study.

The findings shed light on the cascade of events that occur when MECP2 is lost and suggest gene expression changes likely lead to the neuronal and behavioral characteristics of the condition, the researchers say.

Rett syndrome is a rare condition, usually caused by variants in MECP2. The gene encodes a protein that is thought to primarily silence other genes. But studies have shown that genes are both up- and down-regulated when MECP2 protein is missing.

“We didn’t quite understand why genes go in both directions, why some go up and some go down,” says the study’s principal investigator, Huda Zoghbi, professor of human genetics at Baylor College of Medicine. Zoghbi is also director of the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

One hypothesis put forward to explain these findings is that gene down-regulation is a secondary consequence of other changes triggered by a lack of MECP2, such as reduced neuronal function.

Some research also suggests Rett syndrome is a consequence of changes that occur in MECP2’s absence during postnatal development, when the protein’s levels would ordinarily rise.

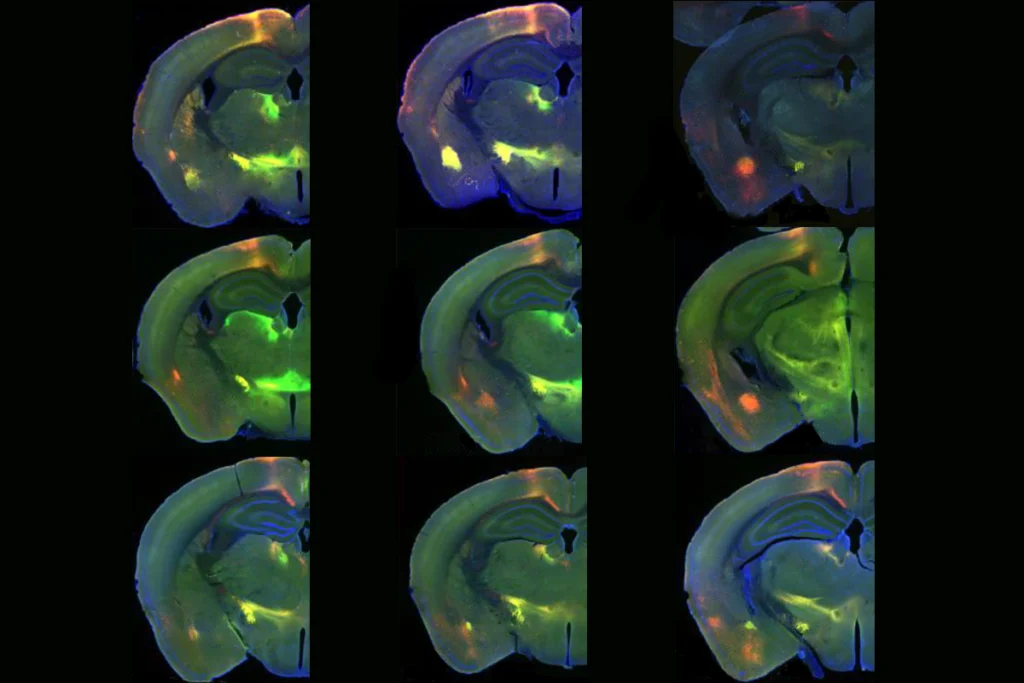

But the new work contradicts both ideas. After Zoghbi and her colleagues deleted the gene in adult mice aged 16 weeks, by which point MECP2 levels have stabilized, genes were both up- and down-regulated within a week. Meanwhile, altered neuronal function only appeared after six weeks.

And genes dysregulated in the adult knockout mice largely overlap with those altered in mice lacking MECP2 from birth, a comparison with existing data revealed, suggesting the changes occur independently of development. The team reported their findings in Neuron in February.

A

lthough Rett syndrome is often cast as a neurodevelopmental condition, the findings fit with the idea that MECP2 is a neuro-maintenance protein, says Adrian Bird, Buchanan Professor of Genetics at the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the study.In 2007, Bird and his colleagues found that many Rett syndrome traits can be reversed by restoring the protein in adult mice.

“You don’t need this protein to make a brain or a nervous system, but you do need this protein to keep it going,” he says.

In the new work, Zoghbi and her colleagues bred mice that carry a copy of MECP2 that can be deleted by injecting the animals with a hormone. Although Rett syndrome affects girls almost exclusively, the team used male mice to avoid confounding factors tied to the random silencing of one copy of the gene in females.

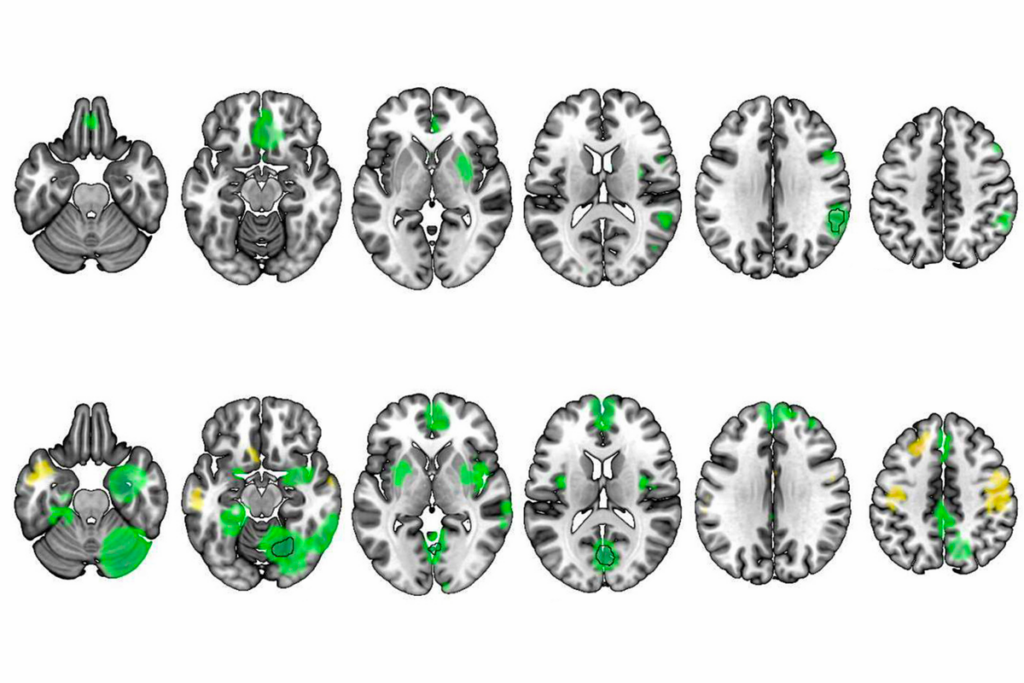

One week after deleting MECP2, 68 genes were differentially expressed in mice lacking the protein compared with controls, RNA sequencing from hippocampi showed. Of these genes, 40 were up-regulated, and 28 were down-regulated.

The number of dysregulated genes increased from one to four weeks after deletion, with thousands of genes dysregulated in the knockout mice after four weeks. Many dysregulated genes were also consistent over time.

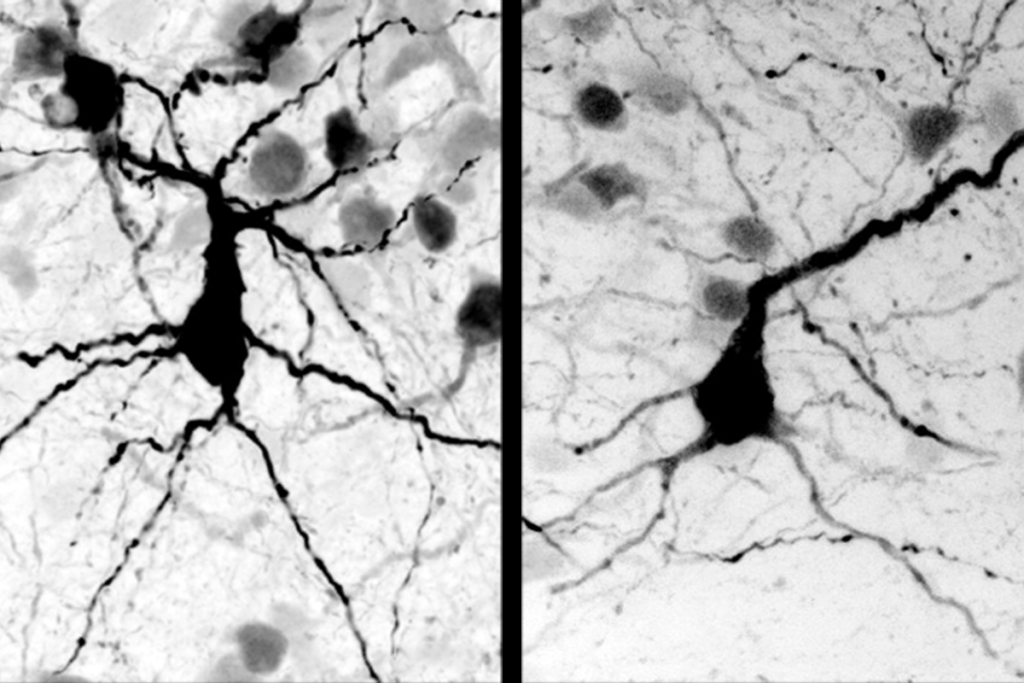

Up- and down-regulated genes exhibited subtle changes in histone marks—chemical tags added to proteins around which DNA coils that help regulate gene expression. Among the first changes the researchers noticed was a decrease in acetyl tags at H3K9 and H3K27 in down-regulated genes. These modifications typically mark gene activation.

“That gave us a clue, perhaps, as to why some genes go down,” Zoghbi says.

B

ehavioral and physiological changes appeared at different time points after MECP2 loss. Knockout mice gained more weight from three weeks onward and were less active after four weeks compared with controls.At six weeks, long-term potentiation—the process that strengthens synapses in response to stimulation¾was diminished in the hippocampus of knockout mice, suggesting a reduction in synaptic plasticity.

The findings point to a set of genes altered after the loss of MECP2 that may be particularly important for neuronal function, the researchers say.

Genes closely tied to MECP2 also hold potential as biomarkers of the protein’s levels.

A major challenge in the development of gene therapies for Rett syndrome is ensuring the right dose of MECP2 is restored, says Walter Kaufmann, adjunct professor of human genetics at Emory University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the research.

“Too much could be as harmful as too little,” he says. Ideally, researchers could measure a biomarker in blood to track MECP2 levels.

Kaufmann cautions that the study’s ability to inform gene therapy trials is currently limited.

“This is a very experimental, artificial situation,” he says. The researchers used male mice and deleted MECP2 in adulthood, but Rett syndrome affects primarily girls, and the protein is missing throughout development, making the realities of the condition more complex.

Although Kaufmann sees the paper as a solid starting point, he says the findings need to be tested at different points throughout life.

According to Zoghbi, it’s also still unclear why MECP2 loss leads to the changes in the material composing chromosomes, or chromatin, she and her colleagues observed. Her team is now working to find out why MECP2 loss affects certain histone marks but not others.