Missing support

Despite the growing number of young adults with autism, few studies have looked at how best to support these teens as they transition into adulthood.

The number of children diagnosed with autism first began rising about 20 years ago, and the children from the first wave of diagnoses in the early 1990s are now becoming adults. Unfortunately, we know little about how to help them with this transition.

Case in point: An analysis published earlier this year found that fewer than two percent of studies of behavioral interventions for autism include people aged 20 or older.

A new review, published 27 August in Pediatrics, backs up this paucity of research. The reviewers looked for studies published in 1980 or later that had at least 20 participants ages 13 to 30. They found five studies that fit those criteria, all of which focused on job-related interventions, such as job coaches.

Figuring out how to most effectively help this group is especially important, the reviewers note, because the period when teens with autism leave high school can be especially difficult. What’s more, most adults with autism live with their parents or in supported homes, fewer than a third are employed and those who are work in low-paying jobs.

Taken together, the studies suggest that job support raises employment rates for young adults with autism, and improves their quality of life and cognitive function.

However, the researchers note that all five studies are of poor quality: The results are inconsistent, the designs potentially biased and the outcome measures uncertain.

The biggest flaw the analysis found is that the studies did not randomly assign participants to different interventions, meaning that participants whose symptoms appeared to improve with job coaching may have been higher functioning from the start than the comparison group.

Studies on interventions for adults with autism should try to standardize the programs they aim to test, follow participants over time to assess the long-term effects, and broaden the outcomes measured, the researchers say.

There are some indications that funding agencies are beginning to focus more on the needs of adults with autism.

At the International Meeting for Autism Research in May, Susan Daniels, acting director of the Office of Autism Research Coordination at the National Institute of Mental Health, said that research on adults, including treatments, is now its own category within the grant budget. (It used to be lumped with autism services overall.) However, this category still gets the smallest chunk of funding, less than two percent of the overall budget.

Recommended reading

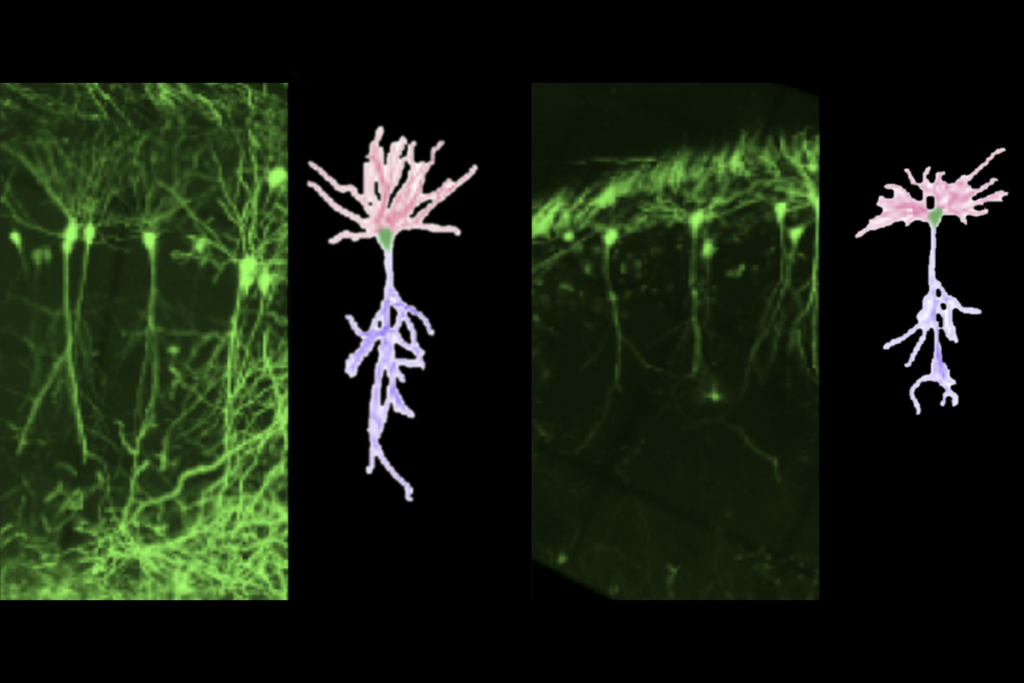

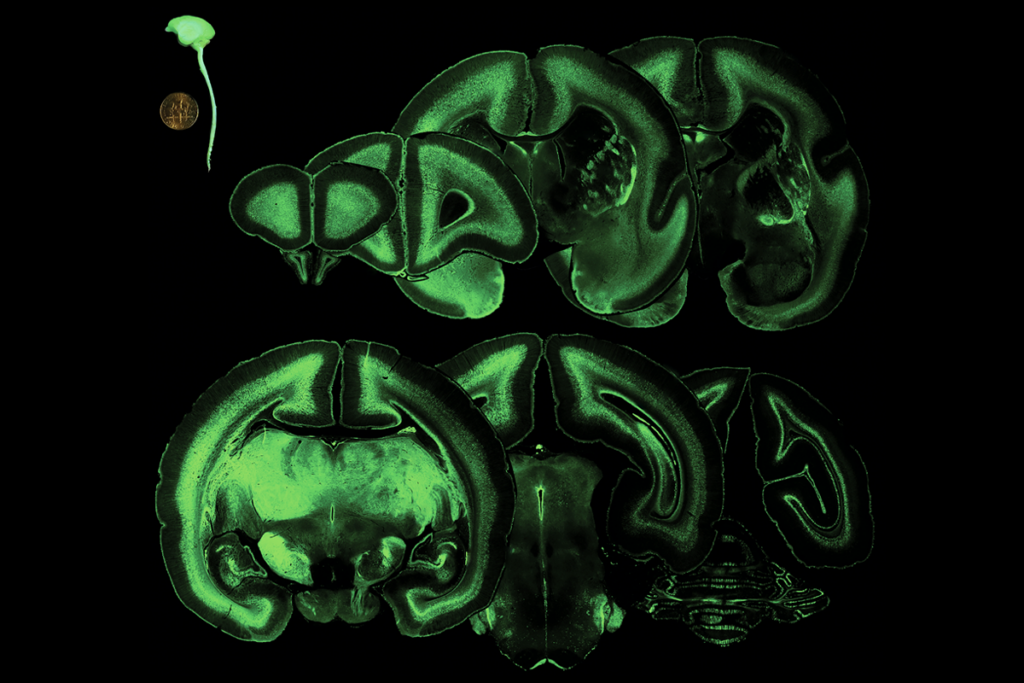

Prenatal viral injections prime primate brain for study

Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Explore more from The Transmitter

BRAIN Initiative researchers ‘dream big’ amid shifts in leadership, funding