Mice missing top autism gene have overconnected brains

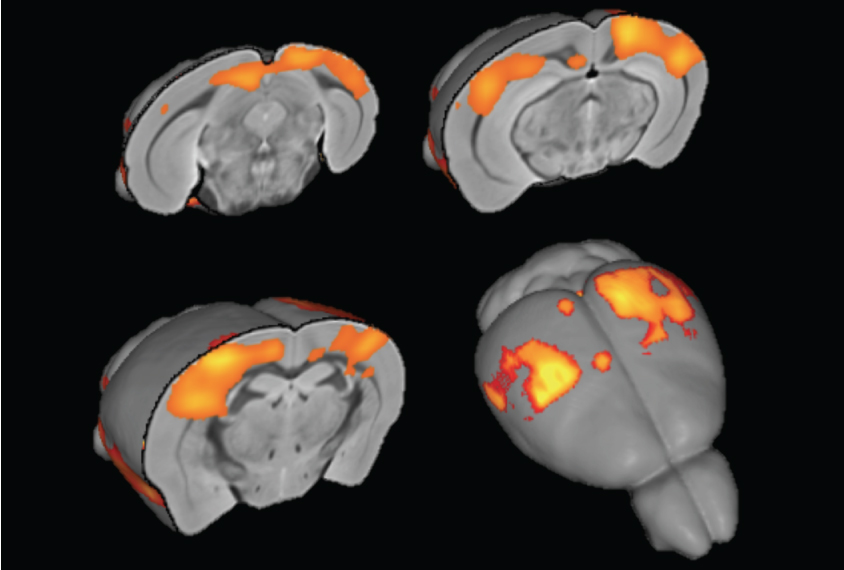

Mice with one inactivated copy of CHD8, a top autism gene, show an unusually high degree of synchrony in neural activity between brain regions.

A new mouse model of a top autism gene suggests that synchrony of brain networks is a better measure of the gene’s effect than is the mice’s behavior1.

This is the fourth mouse model of CHD8 mutations. These mice have one inactivated copy of CHD8. None of the models show significant problems in social behavior, a hallmark of the condition in the people. CHD8 mutations in people, by contrast, nearly always lead to autism with substantial social problems.

In the new study, researchers focused on the mice’s brains. Mice with an inactivated copy of the gene show an unusually high degree of synchrony, or ‘connectivity,’ between brain regions, they found.

If the findings hold up, they could be used to tailor treatments in people with autism, says lead investigator Albert Basson, reader in developmental and stem cell biology at King’s College London.

“One particular treatment might be effective in patients with CHD8 mutations, but it might actually make patients with a similar but opposite [pattern of connectivity] worse,” Basson says.

The absence of social problems in the mouse models underscores how difficult it is to recapitulate this core feature of the condition in mice, says Raphael Bernier, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington, who was not involved in the work.

“Having seen thousands of children with autism now, kids with CHD8 [mutations] are what I think of as the prototypical child with autism,” Bernier says. “Maybe [social behavior] just doesn’t play out in mice.”

Subdividing autism:

CHD8 regulates the structure of chromatin — the coiled complex of DNA and proteins — and the expression of hundreds of genes, including many linked to autism.

Many of CHD8’s targets guide neuronal fibers to their locations in the developing brain, the researchers found. That insight indicated that CHD8 mice may have unusual long-range brain wiring.

To explore that possibility, Basson collaborated with Alessandro Gozzi, who scans mouse brains using functional magnetic resonance imaging.

When the mice are at rest — meaning they are not actively engaged in a task — activity across connected regions in their brain is highly synchronized, the team found. This synchrony is particularly evident between the auditory cortex, which processes sound, and the hippocampus, a learning and memory hub. The results appeared 13 April in Cerebral Cortex.

Mice with mutations in any of three other autism genes — 16p11.2, CNTNAP2 and SHANK3b — show diminished connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and other brain areas2,3. (The SHANK3b results are unpublished.)

“So we were very surprised that we found this CHD8 hyperconnectivity,” says Gozzi, senior researcher at the Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia in Rovereto, Italy.

Multiple studies in people with autism also have reported reduced connectivity across brain areas, but some have reported high connectivity.

“There perhaps might be some specific autism subtypes characterized by increased long-range functional connectivity rather than reduced,” Basson says.

People with CHD8 mutations tend to have characteristic features, such as a large head, motor delay and wide-set eyes, suggesting that they have a distinct subtype of autism.

Human connection:

It may be too early, however, to conclude that overconnectivity is a consistent aspect of this mutation.

“I think we need to see if it is replicated in another [mouse] model,” says Alex Nord, assistant professor of neuroscience at the University of California, Davis, whose lab described one of the other three CHD8 mouse models last year.

How closely the gene’s function in mice aligns with that in people is also unclear, says Deyou Zheng, associate professor of neurology, genetics and neuroscience at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, who was not involved in the work.

Bernier is already looking for signs of overconnectivity in children with CHD8 mutations, however. “I got really excited about this paper, I have to say,” he says.

Basson and Gozzi plan to scan the brains of mice with mutations in genes related to CHD8, such as KMT2A and KDM5B. Gozzi’s goal is to look at 20 strains lacking different autism genes by the end of this year.

References:

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt