Memory and sense of self may play more of a role in autism than we thought

When it comes to recalling personal memories, girls with autism may be more like typical developing girls than like boys with autism.

It’s well known that those with autism spectrum disorders, including Asperger syndrome, develop difficulties with social communication and show stereotyped patterns of behavior. Less well-studied but equally characteristic features are a weaker sense of self and mood disorders such as depression and anxiety. These are connected with a weaker ability to recall personal memories, known as ‘autobiographical memory.’

Research now suggests that autobiographical memory’s role in creating a sense of self may be a key element behind the development of autism characteristics.

Autism is much more common in men than in women, to the extent that one theory of autism explains it as the result of an ‘extreme male’ brain, where women and girls with autism are assumed to be more masculinized. Historically, however, research participants have been predominantly male, which has left gaps in our knowledge about autism in women and girls. Psychologists have suggested that the criteria used for diagnosing autism may suffer from a male bias, meaning that many women and girls go undiagnosed until much later in life, if they are diagnosed at all.

What we remember of ourselves:

This is supported by research that suggests girls with autism develop different characteristics than boys with autism — particularly with respect to autobiographical memory.

Personal memories play a key role in many of the psychological functions that are affected in those on the spectrum. Personal memories help us form a picture of who we are and our sense of self. They help us predict how others might think, feel and behave, and when faced with personal problems, our past experiences provide insight into what strategies we might use to cope or achieve our goals. Sharing personal memories in conversation helps us to connect with others. Recalling positive memories when we feel down can help lift us up, whereas dwelling on negative personal memories can induce depression.

What’s become clear from studies of autobiographical memory in autism is that although those with autism may have an excellent memory for factual information, the process of storing and recalling specific personal experiences, such as those that happened on a particular day in a particular place, is much more difficult. Instead, their memories tend to record their experience in general terms, rather than the specifics of the occasion. This might be due in part to their more repetitive lifestyle, in which there are fewer occasions that stick out as memorable, but also because they are less self-aware and less likely to self-reflect. However, our research suggests that this memory impairment may be exclusive to boys with autism.

Divided by memory:

We examined the personal memories of 12 girls and 12 boys with autism, and compared them with an equal number of girls and boys of similar intelligence and verbal ability without autism. We asked them to remember specific events in response to emotional and neutral cue words such as ‘happy’ and ‘fast.’ We also asked them to recall in as much detail as they could their earliest memories, and recollections from other periods of their lives.

We know that girls tend to demonstrate better verbal skills and are better at recognizing emotions. Might this affect the content and degree of detail they could recall from their own memories? We also wondered whether any gender differences we might find would be replicated between boys and girls with autism, or whether the girls would be more like boys — as predicted by the extreme male brain theory.

What we found was that having autism did lead to less specific and less detailed memories, but only for the boys. The girls with autism performed more like typically developing girls — not only were their memories more specific and more detailed than those of the boys with autism, but like the typically developing girls, their memories contained more references to their emotional states than both the boys with and without autism. So rather than having an ‘extreme male brain,’ the girls with autism were more like girls without autism.

This better autobiographical memory might be one reason why girls and women with autism are often better at masking the difficulties they have with communication and socializing with others, and so are more likely to go undiagnosed. Of course, this poses the question that if they have the building blocks of good communication — access to detailed personal memories — why do they still have autism?

There is some evidence to suggest that the automatic connection between our memories and knowing who we are, and how to use this information to inform how we act in problematic situations, is weaker in those with autism. This means that although women with autism can recall the past, they may not be using their experience to help them understand themselves and solve personal problems.

Even though they may be better able to socialize than boys with autism, this may come at a cost, as greater social interaction brings with it more personal problems, and when problems seem overwhelming this can lead to depression. Indeed, recent research suggests that among those with autism, depression in more common in women than in men. This gender difference with respect to personal memories is an aspect of autism characteristics that has been little studied, and should be explored further.

Lorna Goddard is lecturer in psychology at Goldsmiths, University of London in the United Kingdom.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. It has been slightly modified to reflect Spectrum’s style.

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

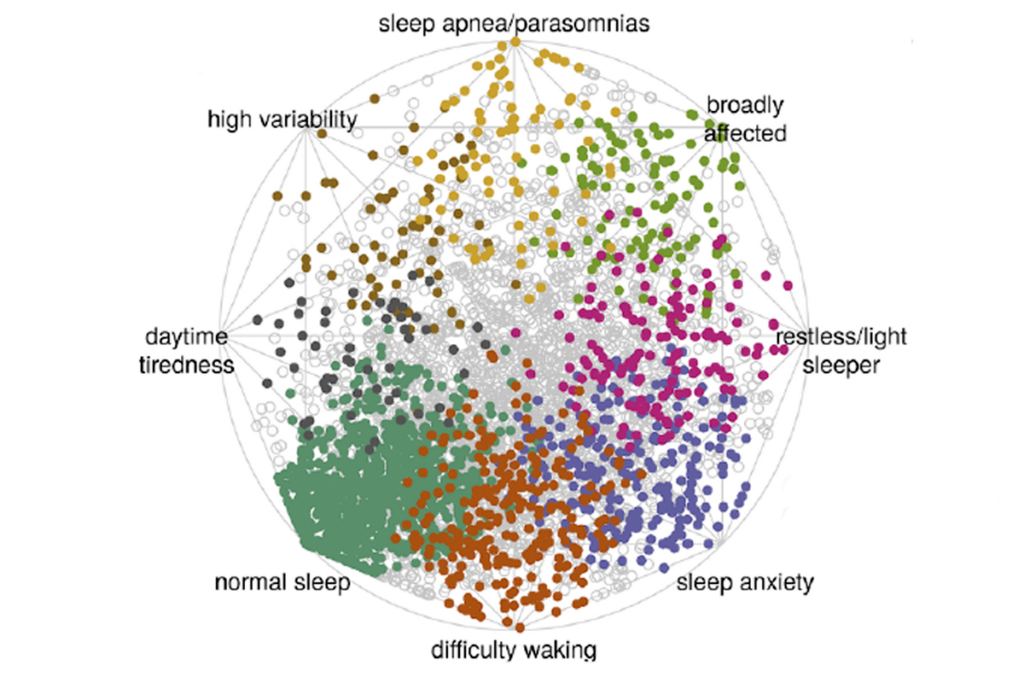

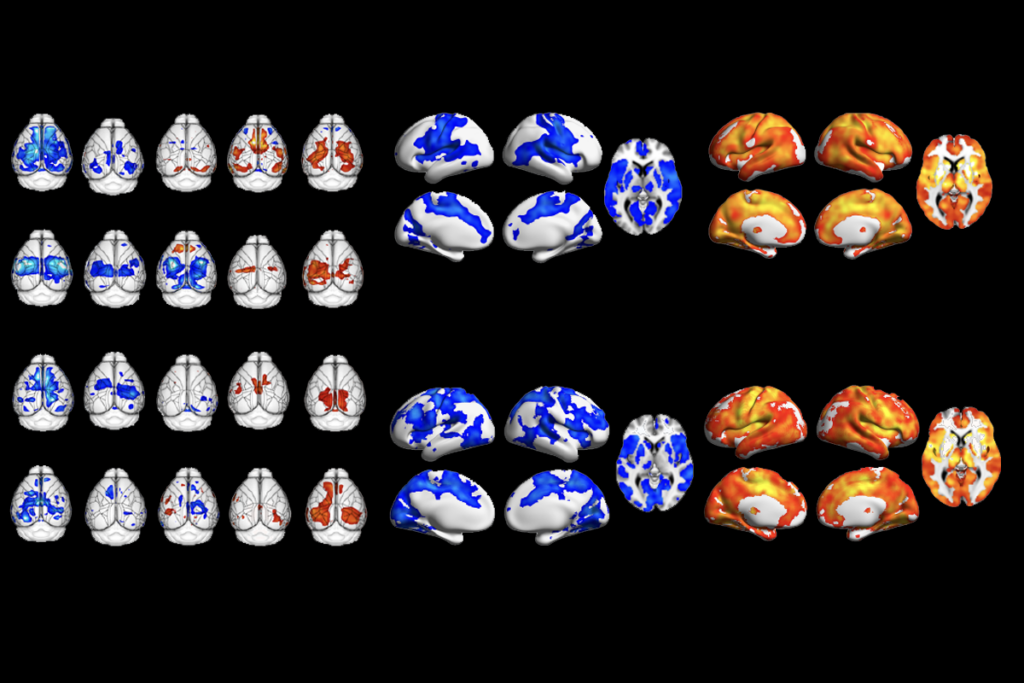

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

This paper changed my life: Shane Liddelow on two papers that upended astrocyte research

Dean Buonomano explores the concept of time in neuroscience and physics