MEGa marker

The brains of children with autism show a delayed response to sound, which may lead to their language problems.

In typical conversation, people speak at a rate of 250 milliseconds per syllable. So imagine how confusing it would be if you lagged behind — even if only by a fraction of a second.

That tiny delay may be what’s provoking the language problems in some children with autism.

Tim Roberts, a radiologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, has been studying the phenomenon for the last decade. He uses magnetoencephalography, or MEG, the ‘hair dryer’ brain imaging method that uses magnetic fields to detect changes in brain activity on the order of 10 milliseconds or less.

Last week, his team reported that when listening to tones of different frequencies, children with autism give brain responses in their right hemispheres about 11 milliseconds slower than healthy controls do. In other, unpublished work, Roberts found a much longer delay — about 50 milliseconds — when children with the disorder process speech sounds, such as ‘ah’ or ‘ou’.

The average age of children in the study was 10 years. If the findings are similar in babies and toddlers with autism, Roberts says this lag measurement may be a reliable marker for diagnosing the disorder, even before other symptoms appear.

MEG would be particularly useful for young children because it’s non-invasive and doesn’t require them to perform a difficult task. On the downside, a MEG scan isn’t a realistic option for the majority of children with autism — there are only about 100 machines worldwide.

Recommended reading

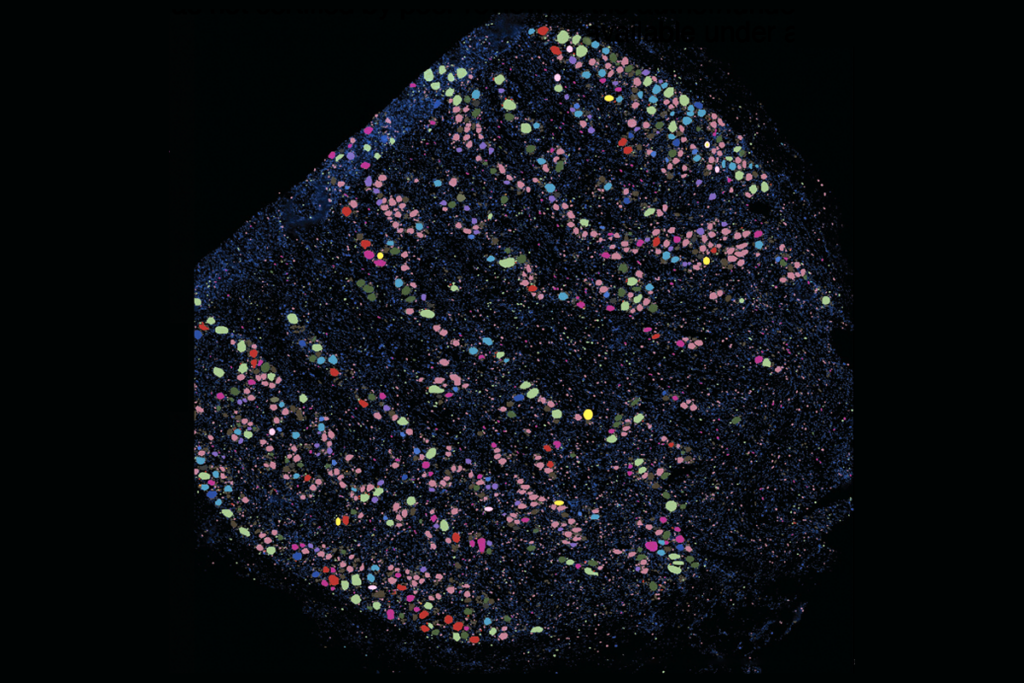

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models