Maternal infection may trigger autism traits via neuronal ‘patches’

Patches of overactive neurons in the brains of mice exposed to inflammation in the womb may lead to autism-like features in the mice.

Patches of overactive neurons in the brains of mice exposed to inflammation in the womb may lead to autism-like features in the mice, a new study suggests1. Treating pregnant mice with an antibiotic prevents these patches in their pups, a related study suggests2.

The patches are found specifically in the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer layer. They consist of atypical clusters of cells and disrupted brain architecture.

A 2014 study reported patches of immature neurons in the cortex of children with autism. Last year, researchers identified this anatomical oddity in mouse pups exposed to infections in the womb3. In the new study, the same team found that overactivity in the neurons in these patches may drive the pups’ autism-like behavior.

The findings fill in key links in the chain of events connecting an infection during pregnancy to altered fetal brain development and autism features. Epidemiological studies suggest maternal infection can increase the risk of having a child with autism by 37 percent.

“The uniqueness of this study is really that it goes all the way from factors in the mothers to behaviors in the offspring,” says co-lead investigator Gloria Choi, assistant professor of brain and cognitive sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. The study appeared 13 September in Nature.

The study also ties infection in the mother to a popular theory of autism: too much excitation in brain signals relative to inhibition.

In the same issue of Nature, the researchers showed that they could prevent the brain patches and behavioral problems by giving pregnant mice vancomycin, an antibiotic. This finding implicates gut bacteria in the effects of maternal inflammation on the developing brain.

Together, the studies represent “a significant advance in understanding potential environmental contributors for autism,” says Sarkis Mazmanian, professor of microbiology at the California Institute of Technology, who was not involved in the work.

Patch work:

Choi’s team injected pregnant mice with a molecule called poly(I:C) that mimics a virus. After the mice gave birth, the researchers measured the time the pups spent burying marbles and interacting with unfamiliar mice — features reminiscent of the repetitive behaviors and social problems seen in people with autism.

The researchers also examined the pups’ brains for neurons that contain parvalbumin. This protein is a marker for a class of neurons that inhibit brain activity. Parvalbumin typically shows up throughout a specific layer of the cortex. But the brains of these pups contain patches of neurons that lack the marker.

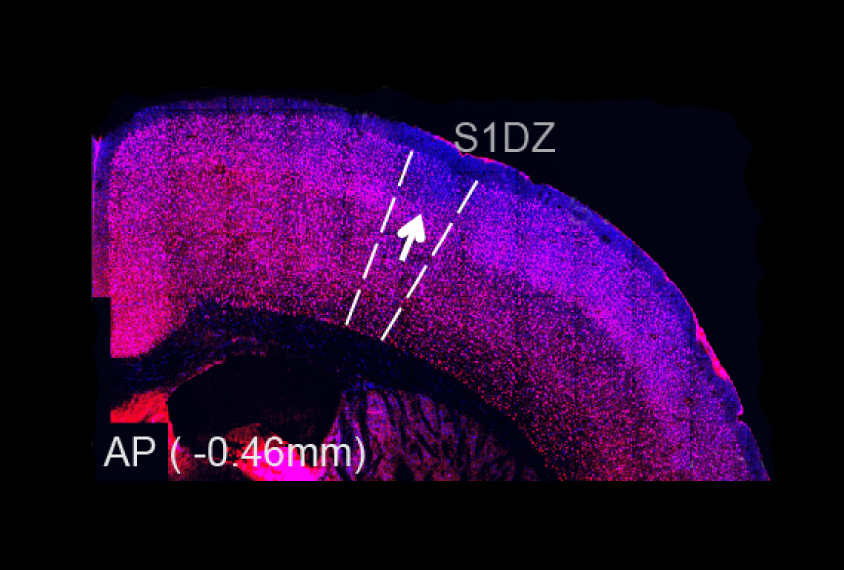

Mice with large patches in or near a region called S1DZ — in a part of the brain that processes touch, temperature and pain — spend more time burying marbles and less time interacting with other mice than those with small patches in the region.

To test whether brains with fewer parvalbumin neurons are overactive, the researchers turned to optogenetics, a technique that uses pulses of light to activate specific neurons. They made mice that express light-sensitive proteins, called opsins, in only S1DZ neurons that are normally inhibited by parvalbumin neurons.

Activated area:

Activating these neurons with flashes of light induces repetitive behaviors and social problems in these otherwise typical mice, the researchers found. This finding suggests that overactivity in the neurons drives the effects of maternal infection.

“The study is really exciting,” says Eric Courchesne, director of the Autism Center of Excellence at the University of California, San Diego, who led the 2014 study in children with autism. “I am so pleased to see that these creative experiments have been able to make progress toward understanding these cortical patches.”

The researchers then traced the connections of S1DZ neurons to other brain regions. They found that the cells connect to the striatum, a region involved in motivation and reward; and the temporal association cortex, which plays a role in recognizing others.

When the researchers activated neurons that bridge the S1DZ and the striatum, the mice spent more time burying marbles but showed no changes in social behavior; when they stimulated only neurons that project to the temporal association cortex, the mice showed social problems but no repetitive behaviors.

“This is just the best evidence you can get today that a brain region is actually involved in behavioral processes,” says Craig Powell, professor of neurology and neurotherapeutics at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who was not involved in the new study.

Gut feeling:

Choi and her colleagues then gave pregnant mice vancomycin, which is known to kill a type of gut bacteria called segmented filamentous bacteria. These bacteria ordinarily spur the production of immune cells that produce a molecule called interleukin-17A (IL-17A).

The vancomycin treatment prevents the rise in IL-17A that accompanies infection in the pregnant mice, and normalizes the pups’ behavior, the researchers found.

The researchers then explored whether bacteria found in human intestines also affect levels of IL-17A in mice. They found intestinal bacteria can also increase IL-17A production in the pregnant mice and trigger behavioral changes in their pups.

“Gut bacteria in maternal intestines play a critical role in shaping brain development in fetuses when mothers are exposed to inflammation,” says co-lead investigator Jun Huh, assistant professor of infectious diseases and immunology at the University of Massachusetts in Worcester.

Eliminating certain gut bacteria may minimize the autism risk associated with maternal infection. But it is too soon to consider treating pregnant women with antibiotics to reduce autism risk, says Sarah Gaffen, professor of rheumatology at the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the new study.

References:

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt