Maternal infection may alter neuronal signals, connections

Pups born to pregnant mice infected with a mock virus are known to show changes in their immune system. These effects may in turn impair proper brain signaling, according to results presented Saturday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Editor’s Note

This article was originally published 10 November 2013 based on preliminary data presented at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego. We have updated the article following publication of the study 15 February in Neuropsychopharmacology1.

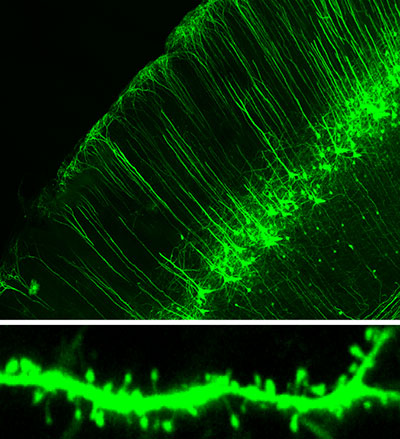

Dendrite drop: Neuronal projections in the cortex of the offspring of infected mice are less dense than those in controls.

Pups born to pregnant mice infected with a mock virus are known to show changes in their immune system. These effects may in turn impair proper brain signaling, according to results published Saturday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Infection during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of autism and schizophrenia. Researchers have been able to mimic this effect in mouse and monkey models.

In both people and mice, the offspring of infected mothers have altered levels of cytokines and chemokines, signaling molecules of the immune system. It’s unclear how that leads to the impaired neuronal signaling observed in the new study, says investigator Anna Dunaevsky, associate professor of developmental neuroscience at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

“The question that is hardest to get at is how do you go from the altered cytokine levels to altered synaptic changes?” she says.

For the study, the researchers used two mouse strains that express fluorescent proteins in either Purkinje neurons (PCP2-EGFP mice), a type of neurons in the cerebellum, or in a subset of neurons in the cortex (thy1-YFPH mice). The researchers gave pregnant mice poly I:C, an acid that simulates infection and activates the immune system.

The pups of PCP2-EGFP mice cry less when separated from their mothers and have fewer Purkinje neurons in the cerebellum compared with controls, both features reminiscent of autism. The mice also compulsively bury more marbles, an action comparable to the repetitive behaviors seen in people with autism, [and they show subtle social problems].

Immune levels:

The researchers then examined the mice’s cortex and cerebellum. A [2013 study] found different levels of cytokines in the cortex and hippocampus of mice whose mothers had infections during pregnancy2, but the cerebellum is less studied in this respect, Dunaevsky says.

The new study found that cells in the cortex and cerebellum have altered levels of chemokines and cytokines during the first four weeks of life, when synapses, or neuronal junctions, are still developing.

“What we get out of this is that the cytokines and the chemokines are all out of balance,” Dunaevsky says.

For instance, levels of TNF-alpha — a cytokine that regulates the ability of synapses to change with experience — and of its receptor protein TNF-R1, are both elevated in the pups’ cerebellum compared with controls.

An analysis of synapses in the cerebellum found a [31] percent drop in levels of cerebellin 1, a protein that is responsible for the organization of synapses. Cerebellin 1 binds neurexin, a synaptic protein linked to autism.

The researchers next looked at dendritic spines, neuronal branches that receive signals. [Neurons from the cerebellum of] pups born to infected mothers [have fewer dendritic spines] than [do those of] control pups. [The researchers also found evidence for a reduction in synapses.]

During typical development, dendrites continually grow and retract from the neuron. Imaging the dendrites seven times over 90 minutes showed that those in the pups born to infected mothers are less dynamic than those in controls, even when the mice are older, between 17 and 19 days old.

“So not only are there fewer spines, but the spines that are there are less dynamic,” Dunaevsky says.

Not surprisingly, her team found that these mice also have fewer excitatory signals on the receiving ends of the synapses in the somatosensory cortex. The researchers induced illness in the C57BL/6 mouse, a commonly used strain with a well-categorized cortex, for this last experiment.

For more reports from the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

References:

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025