Maternal antibodies may affect brain size in autism

The action of certain maternal antibodies on the fetal brain may underlie the large brain size seen in some children with autism, according to preliminary findings from both monkey and human studies presented at a conference in Boston last week.

- Immune inheritance: Prenatal exposure to certain antibodies is linked to large head size in both monkeys and people.

The action of certain maternal antibodies on the fetal brain may underlie the large brain size, or macrocephaly, seen in some children with autism, according to preliminary findings from both monkey and human studies presented at the 13th International Professional Conference on Williams Syndrome in Boston last week.

Previous research has shown that about ten percent of women who have children with autism produce antibodies that bind the fetal brain. These antibodies are not seen in women with typical children or developmental delay, said David Amaral, director of research at the University of California, Davis MIND Institute, who presented the research.

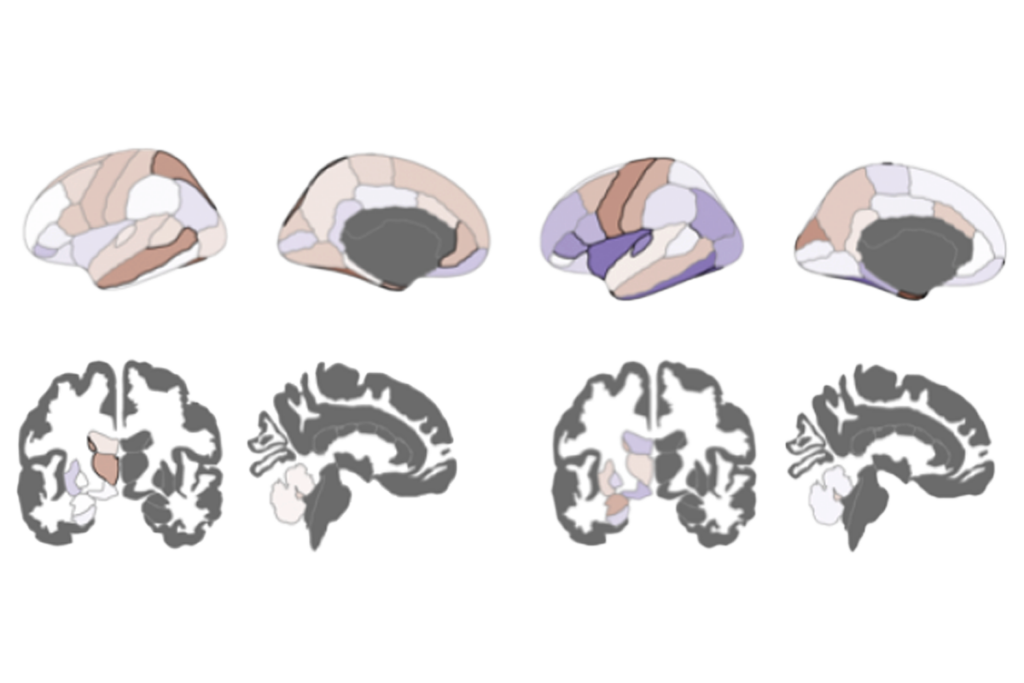

Studying children in the Autism Phenome Project (APP), a large-scale effort to categorize different subgroups of autism, Amaral’s team found that children of women who have these antibodies have the largest brains in the sample. The brain volume for this group is about 14 percent larger than average in the study and completely outside the range of typical controls.

A major question, however, is how macrocephaly, found in about 10 to 20 percent of children with autism, contributes to symptoms of the disorder.

“What does larger brain size mean? Is it important?” asks Paul Patterson, professor of biological sciences at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, who was not involved in the research. “I think that’s a critical question.”

But if the preliminary findings are confirmed, and brain size is shown to be relevant to the core symptoms of autism, it could suggest an approach to preventive therapy in this subgroup.

“There’s a lot of work to be done before you can say this is a cause of autism, but once we do, you can do something about it,” Amaral said. “There are lots of techniques used to blunt the effects of antibodies.”

Big brains:

Research from the APP published in December has shown that, overall, the brains of boys with autism are about six percent larger than those of controls. (Not all children with autism who have a larger-than-average brain size were exposed to the antibodies.)

Girls with autism, on average, do not have larger brains. The study also found that boys with regressive autism — meaning that they appeared to develop normally and then abruptly lost language and social skills —are more likely to have larger brains than boys with non-regressive autism and controls.

In an ongoing project to understand the role of these antibodies, researchers at the MIND Institute injected pregnant rhesus monkeys with antibodies derived from the autism mothers, during a period of pregnancy when the fetus is thought to be vulnerable to environmental insults. They then did a series of brain scans using magnetic resonance imaging as the baby monkeys grew up.

Preliminary findings from four male monkeys suggest that prenatal exposure to antibodies purified from mothers of children with autism significantly increases brain size compared with controls. Brain size starts to deviate from the normal course at about 3 months of age, roughly equivalent to 1 year in humans.

“This is an exciting finding because the only difference is the antibody injection,” said Amaral. The researchers are trying to confirm the finding in a larger group.

“The fact that they made the same observation in monkeys and humans strongly supports the notion that the antibodies are making a difference,” says Betty Diamond, professor of medicine at Columbia University in New York, who was not involved in the research. “The numbers are small, so we don’t want to go overboard yet.”

Diamond’s group has shown that mothers of children with autism are five times more likely than a control group of women of childbearing age to have anti-brain antibodies.

The link between large brain size and the symptoms of autism is still unclear, however. Monkeys exposed to maternal antibodies show social impairments, such as inappropriate approaches to other monkeys and inability to negotiate social interactions, said Amaral.

A study published this month by Judy Van de Water, Amaral’s collaborator, found that children exposed to fetal antibodies during pregnancy score lower on the ability to communicate through spoken language than those who were not2.

Overall, children with autism in the APP who have large brains showed no behavioral differences from those with typical head size.

Missing link:

Pending more results, it’s also unclear what the link between antibodies and brain size means.

“We have no evidence whatsoever about what contributes to precocious brain growth in autism, largely because we can’t get postmortem brains at that age,” said Amaral. “If this holds up, we can get cohort of monkeys, look at the histology and contribute something to the neurobiology of autism that is impossible to do in human subjects.”

For example, researchers could examine whether these brains have more neurons or glia — another type of brain cell that has been tied to autism — than controls do.

The researchers are also following women who already have one child with autism to study them during subsequent pregnancies. The risk of a sibling of a child with autism also developing the disorder is up to 20 percent higher than in the general population.

“If maternal antibodies are truly pathogenic, the probability that a subsequent child will have autism might be 60 to 80 percent rather than 20 percent,” said Amaral.

Amaral and Van de Water have yet to publish the specific identity of the fetal brain proteins to which the antibodies bind. Published papers refer instead to two protein bands of specific sizes, 37 and 73 kilodaltons.

“But a band is not a protein,” says Diamond. “We don’t know that one mother with antibodies to a 37-kilodalton protein band is the same as another mother with antibodies to that band.”

References:

1: Braunschweig D. et al. Neurotoxicology 29, 226-231 (2008) PubMed

2: Braunschweig D. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 42, 1435-1445 (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Structural brain changes in a mouse model of ATR-X syndrome; and more