Low standards corrode quality of popular autism therapy

Rapid growth and inadequate standards in the ‘applied behavior analysis’ industry may put vulnerable children in the hands of poorly prepared technicians.

W

hen Terra Vance took a course to become a registered behavior technician (RBT) in 2015, she was trying to transition from a career as a teacher to one as a psychologist. To get the supervised hours she needed for her psychology license, she had taken a job working with mentally ill adults for a company in Lynchburg, Virginia.Instead, her employer told her the company had a backlog of autistic children and wanted her to help with that caseload. The employer paid for her to get the RBT certification, which would qualify her to deliver what many researchers consider the gold-standard autism therapy, applied behavior analysis (ABA), under supervision to these children.

Vance completed the online course — a series of videos followed by quizzes from a company called Relias — over a weekend. She was intent on learning the material, she says, but found out later that other students cut corners, letting the videos play while they did other things and looking up quiz answers on their phones. It was easy to pass: If you failed a quiz, you could just re-watch the video and take it again.

Vance had spent 14 years teaching English to middle- and high-school students, and she had developed a reputation for helping autistic students. (She was diagnosed with autism herself in 2017.) But when she started accompanying another RBT on home visits, she felt unprepared, she says. Extra training she received from her employer — on privacy, patient rights and restraint training — did not add to her confidence. No one taught her how to change diapers or adequately manage aggression, she says, which she would have found more useful.

Vance also quickly became skeptical of the kind of therapy she was being trained to deliver. For example, she shadowed a more experienced RBT at the home of a 10-year old boy with autism and intellectual disability who had memorized entire movie scripts. Vance recognized that he was communicating with humor and nuance by choosing lines to recite in various situations. But instead of engaging with him through movie lines, she was told by her supervisors to reward the boy with candy or cereal for following commands and completing trivial tasks, such as stacking blocks.

“They were missing so much about this amazing human by just saying he was like a 3-year old,” says Vance, who now heads NeuroClastic, a nonprofit blogging platform about autism. After a few weeks of working with the boy, Vance was laid off and her supervisor was fired, she says.

The sprawling industry that has coalesced around ABA is causing frustration for many — technicians, clients and experts alike. Plenty of therapists in a wide range of settings, including schools, homes and clinics, do ABA well, and plenty of studies support its value, says Zachary Warren, a clinical psychologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. But ABA’s worth depends greatly on who is delivering it. And as autism diagnoses and demand for ABA have risen over the past decade, how to ensure people are qualified to deliver the therapy effectively has become a point of contention.

Six years ago, the Behavior Analyst Certification Board, a nonprofit corporation that establishes professional credentialing standards for behavior analysts, created the RBT qualification, largely, they say, to ensure uniform standards for the technicians who increasingly do much of the frontline care. Compared with higher levels of certification that call for at least a college degree, these paraprofessionals need only a high school diploma, a 40-hour course, a background check, an in-person assessment and, starting in 2016, a written test.

The new qualification was followed by a surge in the number of people certified to deliver ABA. Critics, however, have challenged the standards for being too lax. It takes hundreds of hours of training over months to qualify therapists to work independently with children, they say. “Forty hours? You’ve got to be kidding me. Put another zero behind that and maybe that would be closer,” says Jon Bailey, an ABA expert at Florida State University in Tallahassee.

And it’s not just the credentials that have come under scrutiny. On-the-job coaching and supervision are supposed to make up for gaps in the training, but some RBTs find that the agencies they work for do not provide much of either. Technicians describe checked-out or overworked supervisors, little guidance and high turnover, which harms clients along with ABA’s reputation. “The RBT is the hands-on person,” Bailey says. “They should have a lot of training, because if they mess up, you’re messing with people’s lives. This is not like somebody burned a hamburger or something.”

Yet, critics say, the agencies that hire RBTs often rely on a vast pool of undertrained labor. These businesses collectively train and employ tens of thousands of RBTs to work with children. “It’s being treated as a money grab in many places,” Bailey says. He estimates that there are hundreds, if not thousands, of these companies in the United States. Some are profitable enough that they have become popular buys for private equity firms.

Some experts are calling for more stringent certification standards. Others in the field — including Melissa Nosik, deputy chief executive officer of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board — maintain that variation in treatment quality exists in many fields. Training requirements evolve, they say, and the system is doing its part to help meet the demand for qualified people to deliver ABA.

In the meantime, families and therapists are left in a tough spot. “If you have a kid with autism, you’re desperate to get those services, and I don’t think you’re willing to wait until we figure out all of the right things about training, fidelity and implementation,” Warren says. “You want services now, and you want to be able to have a workforce that can deliver that.”

Beautiful moments:

T

he roots of ABA date back to the 1930s and the work of psychologist B.F. Skinner, who focused on concepts such as conditioning, reinforcement and responses to stimuli to explain human behavior. Skinner’s behaviorism theory arose around the premise that behaviors can be learned, and that learned behaviors can affect a person’s quality of life. ABA is essentially a method for teaching new behaviors, says Ronald Leaf, a licensed psychologist and director of the Autism Partnership, a California-based agency that provides autism services.ABA can take various forms, including the Early Start Denver Model and pivotal response treatment. Its general aim is to teach language, social and other skills by breaking them down into small parts, often with rewards and a sense of fun worked in to boost motivation. Although scientific support for the method is not rock solid, studies stretching back for decades indicate that, when done well, ABA can facilitate learning and improve social communication, minimize challenging and self-injurious behaviors and improve daily functioning in people with autism, intellectual disability and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, among other conditions.

Anecdotal reports of success abound, too. “It’s amazing when it’s done right,” says B. Lynn, a woman in California whose 20-year-old son was diagnosed with autism at around age 5. (Spectrum is withholding Lynn’s first name and her son’s name to protect their privacy.) The family has worked with several ABA agencies over the years. Her son used to vocalize loudly about 100 times a day, making it seem like he was minimally verbal, even though he can be chatty. With help from an ABA therapist, though, at age 14 his vocalizations dropped to fewer than five a day, and he was able to attend school with peers for the first time since he was 5. ABA therapists also helped potty-train the boy; they taught him to shower and eat more than one color of food. “From the ones with really good training who are really good people, we’ve seen huge, huge growth,” Lynn says.

When done well, ABA often looks like play, with learning happening through shared engagement in activities, Warren says. When he evaluates a child, he looks for opportunities to connect with the child through activities that dovetail with the child’s interests, he says. “If we have more moments of engagement like that, we have more moments to be teaching about language or different ways of playing or interacting,” he says. “Most parents are like, ‘Oh, yeah, absolutely. I want those beautiful moments that I know are real and tangible with my child.’”

But many ABA therapists may not be trained to create such moments. In one notorious case from the 1970s, an applied behavior analyst in Florida abused adolescents with intellectual disability by beating them for running away, shaming them for lying and forcing them to masturbate if they were caught masturbating.

The majority of therapists are not abusive. Many are just not taught to adjust ABA to an individual child, which is critical to the method’s success. Part of the problem is that most RBT training courses teach formulaic, child-unfriendly techniques, as if delivering ABA were like following a recipe, Leaf says. For example, technicians might be taught to use simple instructions, such as “Do this,” instead of varying language and altering words to match a child’s ability to process complex instructions, such as “Do what I’m doing,” or “Can you copy me?”

Many courses teach technicians to do the exact same thing with every client, in the same sequence every time, Leaf says. They also advise the use of explicit rewards, such as candy, which can seem demeaning at times and don’t work as well as the positive feedback that occurs naturally through interaction. Vance was appalled that her RBT course instructed her to buy a clicker at a pet store. The course instructed technicians to use the clicker to reinforce desired behaviors in children, she says, just as pet owners might use it to train dogs.

Autistic adults who had ABA as children have criticized the therapy for forcing them to act in ways that made them uncomfortable, for pathologizing their neurodiversity and for being too scripted, inflexible and robotic. Parents say that a child can be discouraged by bad ABA, and that a lack of progress is harm enough, given the stakes and the cost. Over the years, Lynn’s son had a few therapists who talked down to him, she says, which irritated and frustrated him, so they did not last long. “We can see a definite difference when we don’t have great people.”

Leaf has testified in lawsuits related to ABA that included questions about legally ‘meaningful’ progress. One case, in which he served as an expert witness for a school district, involved a 9-year-old boy who was doing virtually identical tasks every day for five years and had made minimal progress in that time. His lessons never changed to accommodate his shifting needs or to respond to what was not working. “When I have a child at 9 o’clock in the morning, I’m going to do something different at 9:10, because good ABA adjusts to the learner constantly,” Leaf says. “You have to be well trained to do that.”

Rapid expansion:

Q

uestions about qualifications have long been an issue for the field. In the 1970s, experts realized they needed uniform standards and a way to certify that therapists are qualified, says Gina Green, chief executive officer of the Association of Professional Behavior Analysts in San Diego, California.In 1983, Florida pioneered the first state ABA certification program, and several other states adopted similar standards the following decade. In 1998, a behavior analyst named Jerry Shook, who worked at the Florida health department, created the national nonprofit Behavior Analyst Certification Board. The board developed credentials for a ‘board-certified behavior analyst’ (BCBA), which requires at least a master’s degree, and a ‘board-certified assistant behavior analyst’ (BCaBA), which requires a bachelor’s degree. They decided to develop a technician credential more than a decade later, Nosik says. In 2014, the board added an entry-level certification.

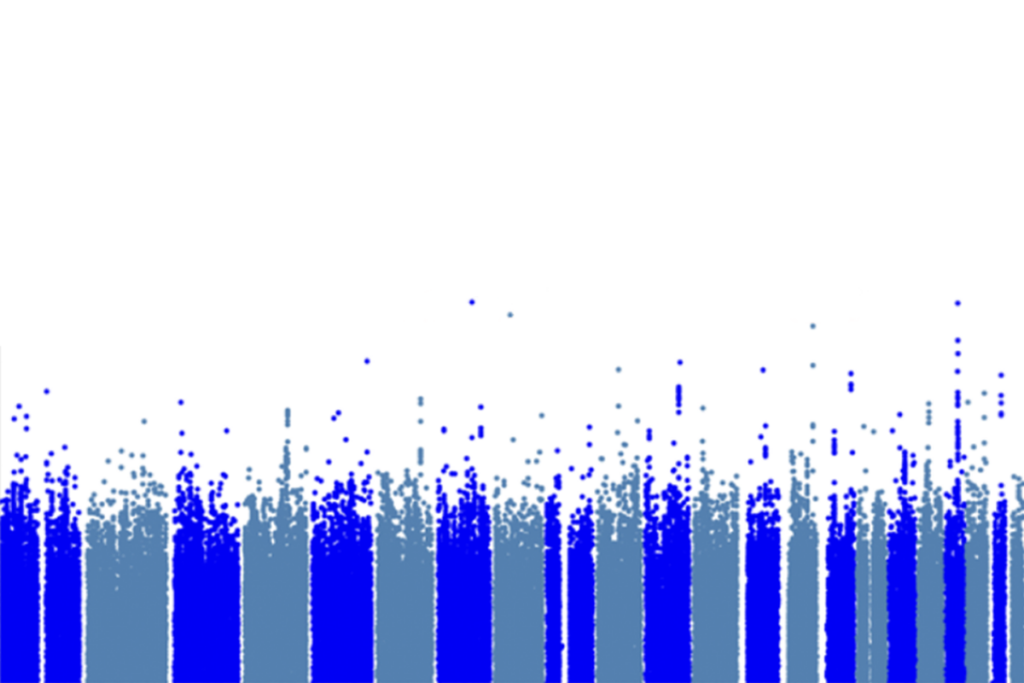

Alongside the credentialing efforts, the field has quickly grown in popularity, buoyed by a rise in autism prevalence. In the U.S., the ranks of BCBAs grew from fewer than 400 in 2000 to 16,000 in 2014, three-quarters of them working with autistic people, according to certification board data. By 2017, the board had anointed more than 34,000 RBTs worldwide. By October 2020, almost 83,000 people had received an RBT certification (and more than 42,000 had become BCBAs).

The swelling ranks of RBTs helped address a numbers problem, Warren says. A BCBA can directly serve only a small number of children. For example, at 20 hours a week per child, a BCBA can help only two children in a 40-hour week. With RBTs working under them, BCBAs can handle many more clients.

At the same time, state mandates for insurance coverage of ABA (all states now have them) have reshaped the industry, experts say, opening up the potential for greater profit for agencies that shift more hours and responsibility to RBTs. Whereas entry-level BCBAs earn about $60 to $80 per hour, according to several job postings, a typical RBT makes less than $20 per hour. At the same time, insurance companies reimburse ABA firms an average of $95 an hour for a BCBA, compared with an average of $65 an hour for an RBT.

Industry changes may have come with growing pains, as many RBTs have expressed concerns about their lack of supervision from BCBAs: Every year, 1,200 to 3,600 messages — from RBTs, BCBAs and families — pour into the ABA Ethics Hotline, which Bailey has run in one form or another for more than a decade. According to board regulations, RBTs should receive half an hour of direct supervision for every 10 hours of services (5 percent of their monthly hours). Supervisors also monitor therapy indirectly by reviewing daily progress notes, Green says. But the hotline regularly hears from RBTs who have not seen their supervisors in weeks, and sometimes months.

The hotline also hears from parents who are not happy with how RBTs interact with their children. One family installed a hidden camera, which showed their RBT repeatedly slapping their child in the face. “I hear from parents that say, ‘This person doesn’t seem to know what they’re doing.’ And then I hear from RBTs that say, ‘I wasn’t trained to do this; I’m not getting any help. I’ve only worked with, say, children with language problems, and now they’ve given me a teenager who’s aggressive,’” Bailey says.

RBTs regularly vent their frustrations on Reddit too. One reported having no in-person training and not knowing what to do with clients even after four months on the job. A case manager described a company that would “just hire anybody” and throw them into one-on-one situations with children without any supervision. Some children, the manager said, had not seen a supervising BCBA in six months. (None of the commenters responded to requests for interviews.)

Realistically, BCBAs could oversee a maximum of 5 to 10 RBTs at once (depending on who the clients are), given the time it takes to observe, provide feedback and complete paperwork, Bailey says. But many are assigned to manage 15 to 20 RBTs, he says, in part because there are too few BCBAs to go around: More than half of U.S. counties have no BCBAs at all.

RBTs can make choices that hurt families, says Catherine Lord, a clinical psychologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. Plenty of schools and agencies deliver high-quality ABA, she says, but she worked with one autistic child who was seeing 16 separate RBTs. None would commit to more than two hours a week, because they were paid hourly and if the client got sick or went on vacation, the RBT would lose that pay.

RBTs also sometimes leave clients if they feel unprepared and unsupported to handle that person’s difficult behaviors — a disruption that can hurt the client’s progress. When Shannon Des Roches Rosa’s high-support autistic son was 12, the family turned to an agency near their Silicon Valley, California, home. For the first couple of years, no technician the company sent lasted more than a few months. The family cycled through at least 10 technicians, says Rosa, who is senior editor of Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism.

“A lot of them didn’t have what it takes to work with a person who has a lot of autistic behaviors,” Rosa says. And the turnover and poor care took its toll. Rosa’s son was often miserable, which was stressful for Rosa. “Whenever there was a new therapist who arrived in the house, it was worse for me than having nobody there,” she says.

Quality control:

I

n the early days of ABA, researchers in the field never dreamed that outside companies would take it over and overhaul it in ways that would harm its reputation, Bailey says. “Right now, [ABA] is known as the gold standard for treatment of autism, and that’s because we have so much research on this,” he says. “But if you don’t translate the research into practice, and if you don’t monitor the practice, it’s not the gold standard anymore.”The accreditation board for ABA continually reevaluates and revises credentialing standards, Green says, to ensure the bar is set sufficiently high. For example, in 2019, the board added a new certification requirement that RBTs must demonstrate certain skills on the job with clients instead of during role play with supervisors. And the mandatory eight-hour supervision-training course has been revised to include more details about how to effectively oversee RBTs.

There are scant data to support any benefits from ABA delivered by RBTs, Warren adds. “I think there’s a limited amount of information” about outcomes for children who work with RBTs, Warren says. “They’re probably not the ones that are making these huge gains or the big gains that we’re seeing in some of the studies for some of our kids.”

To boost the numbers of well-trained therapists, Leaf and his colleagues launched their own 40-hour RBT certification course in March 2020 that emphasizes flexibility and responsiveness instead of rigidity and script-following. Though 40 hours is less than ideal, Leaf and his coworkers worried that companies would not adopt a longer program. And to “eliminate the revenue stream of agencies that are providing horrible training,” he says, they also made their course free and available online with funding from Dara Khosrowshahi, chief executive officer of Uber, and his wife, Sydney Shapiro. In its first six months, more than 89,000 people around the world took it, Leaf says. They do not track how many students go on to become certified, but the number who have taken their course is already more than the total number of certified RBTs.

Leaf and his colleagues are advocating for changes at the Behavior Analyst Certification Board to increase RBT training hours to at least 80, and to adjust that training to reflect a more progressive, less protocol-driven approach. They are also studying training methods to see which styles of reinforcement, correction and instruction work best. Already, their work has produced surprises: For example, even though one-on-one services have long been considered the best way to deliver ABA, their research suggests that small-group interventions can work just as well for teaching basic language skills. And another small study showed that 32 two-hour sessions of their new flexible version of ABA can produce improvements in social behavior that persist for at least four months.

In a separate effort, the California-based Behavioral Health Center of Excellence has started offering accreditation for behavior analysis to organizations and companies that use high standards, says Bailey, who is on the center’s board of directors. When his students at Florida State University are looking for jobs, he tells them to look for companies with the Behavioral Health Center of Excellence certification to ensure they are working for high-quality employers. Families can do the same when looking for providers, he says, but only about 400 agencies nationwide have earned the accreditation. Through the hotline, Bailey hears from parents who have just one or two agencies in total to choose from within a 20-mile radius — and those agencies have months-long waitlists.

During her brief stint as an RBT, Vance found out she was pregnant with her daughter, who is now 4. When her daughter was almost 2, she was assessed for language delays and diagnosed with autism. Vance never considered seeking ABA for her. She sees too much potential for harm as a tool to control how children behave. “I think I’m raising a phenomenal, thoughtful, caring, emotionally supported, happy child,” she says. “That’s what matters.”

Vance still thinks about the boy who quoted movie scripts and the failure of a conscripted therapy to connect with him. “He thought in archetypes, like all of the greatest spirits from literary and historical acclaim, and that was how language acquisition and communication worked for him,” she says. “But the tasks he was given were so menial. The focus should be on how to help other people recognize that kind of brilliance.”

Recommended reading

Revised statistical bar extracts less-common variants from autism genetics studies

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

Explore more from The Transmitter

Tom Griffiths describes how neural networks, logic and probability theory together explain cognition