Low intelligence, repetitive actions tied to self-injury in autism

People with autism who are admitted to the hospital for self-injury tend to have low intelligence quotients and severe repetitive behaviors.

People with autism who are admitted to the hospital for self-injury tend to have low intelligence quotients (IQs) and severe repetitive behaviors, according to a new study1.

Not all individuals who engage in self-injury at home do so when admitted to a hospital, where professionals watch them closely and institute individualized behavior plans. The new findings could help clinicians identify those most at risk for harming themselves in a hospital setting.

“Self-injurious behavior is really hard to treat, and it’s hard to watch,” says Matthew Siegel, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Tufts University in Boston and the study’s senior investigator. “Knowing these risk factors could prepare [hospital staff] better for what they’re going to need to do.”

Up to half of people with autism engage in self-harm, such as biting, scratching or hitting themselves.

The prevalence is typically higher among those with autism who end up in the hospital, perhaps because self-injury is often the reason for admission2.

Previous research on self-injury and autism covered a broad swath of the autism community. The new findings spotlight the behavior in people admitted to hospitals, who tend to be at the more severe end of the spectrum.

“The characteristics of self-injury [in this population] and the features associated with their self-injury can be very different,” from those of individuals with less severe autism, says James Bodfish, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, who was not involved in the study.

New environments:

Siegel and his colleagues analyzed data from 302 young people with severe autism, aged 4 to 20 years, in six psychiatric units within a national network. The participants spent an average of 25.6 days in the hospital.

The participants took nonverbal IQ tests upon admittance; parents and caregivers completed questionnaires to assess repetitive behaviors, autism severity and self-injurious behavior at home.

The hospital staff monitored the participants and reported whether an individual engaged in self-injury by marking either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ at various intervals. The staff considered self-injurious behavior significant if the person engaged in the behavior at least once a day.

About one in four participants hurt himself both at home and in the hospital. About half had engaged in self-injury at home but did not do so at the hospital, and one person engaged in the behavior only at the hospital. The rest did not engage in self-injury or did so less than once per day.

“We often see a dramatic difference in problem behaviors just right off the bat due to that level of care [at the hospital],” says Jill Fodstad, assistant professor of clinical psychology in clinical psychiatry at Indiana University in Indianapolis, who was not involved in the study.

Early intervention:

Those who harmed themselves at home and at the hospital have an average nonverbal IQ score of 58. This score is about 18 points lower than the average IQ of those who exhibited the behavior only at home and nearly 30 points lower than the average score of those who injured themselves infrequently or not at all. The results appeared 24 January in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Self-injury in the hospital (as well as at home) is also associated with a relatively high frequency of repetitive behavior — and with a greater severity and frequency of self-injurious behavior. Like some previous reports, this one found that the behavior is equally common in girls and boys.

The results may help clinicians better prepare for incidents of self-injury and prevent or limit the harm to the person, Siegel says.

They could also help parents spot early signs of self-injury before the behavior begins. If a young child has a low nonverbal IQ and frequent repetitive behaviors, clinicians might advise parents to begin preventive measures. “The earlier you can intervene, the better,” Siegel says.

The researchers are trying to find the biological mechanisms that might explain why those with severe autism engage in self-harm.

References:

Recommended reading

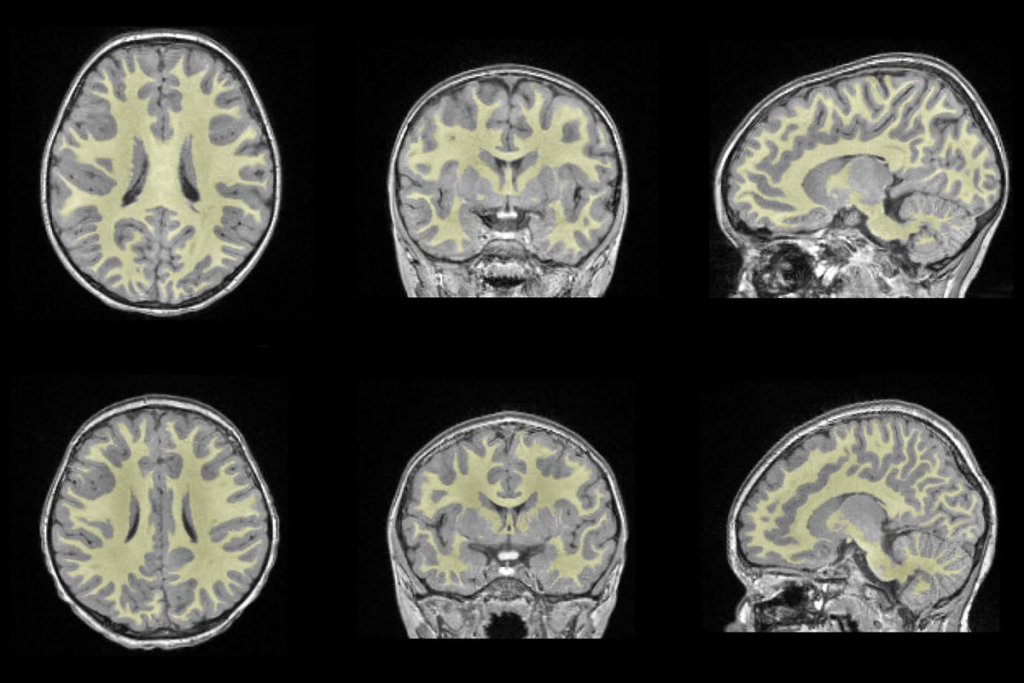

White-matter changes; lipids and neuronal migration; dementia

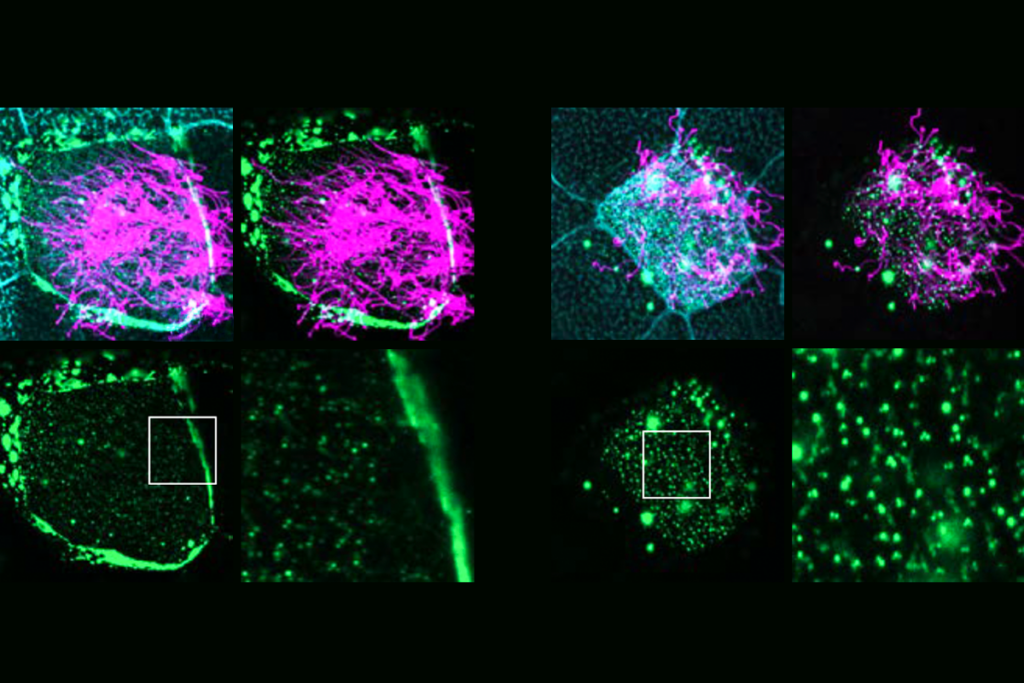

Many autism-linked proteins influence hair-like cilia on human brain cells

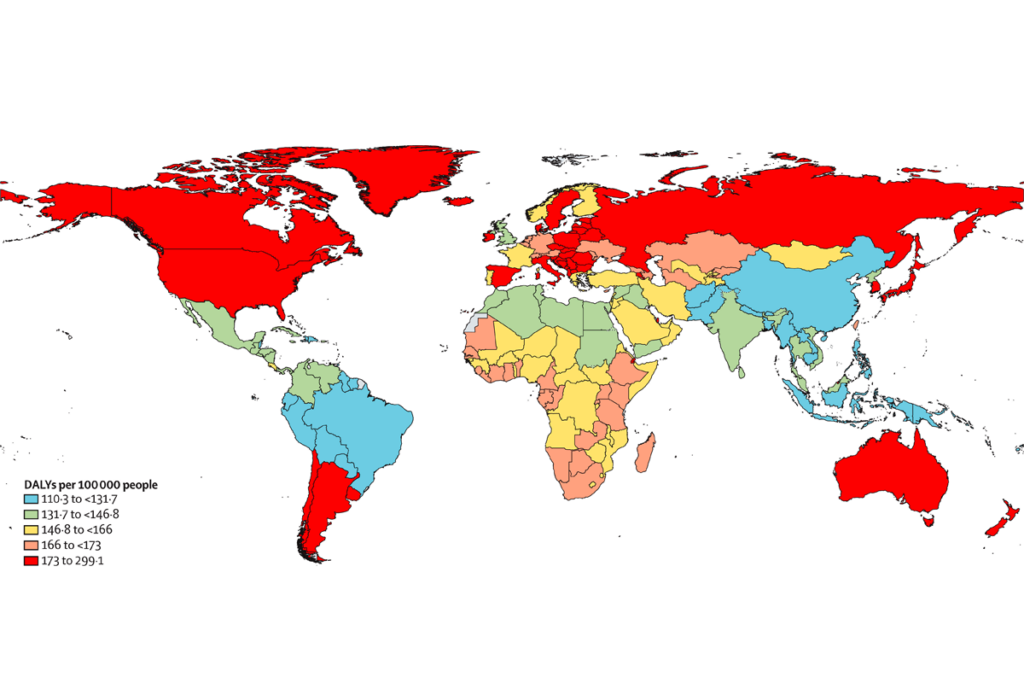

Functional connectivity; ASDQ screen; health burden of autism

Explore more from The Transmitter

David Krakauer reflects on the foundations and future of complexity science

Fleeting sleep interruptions may help brain reset