Mutations in the autism-linked gene ASH1L change how neurons grow and develop, according to two unpublished studies presented virtually this week at the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome. (Links to abstracts may work only for registered conference attendees.)

ASH1L helps regulate chromatin, the mass of DNA and proteins in the nucleus of a cell.

Blocking a protein that is overactive when ASH1L is deficient reverses the structure changes seen in neurons lacking the gene, one of the studies shows.

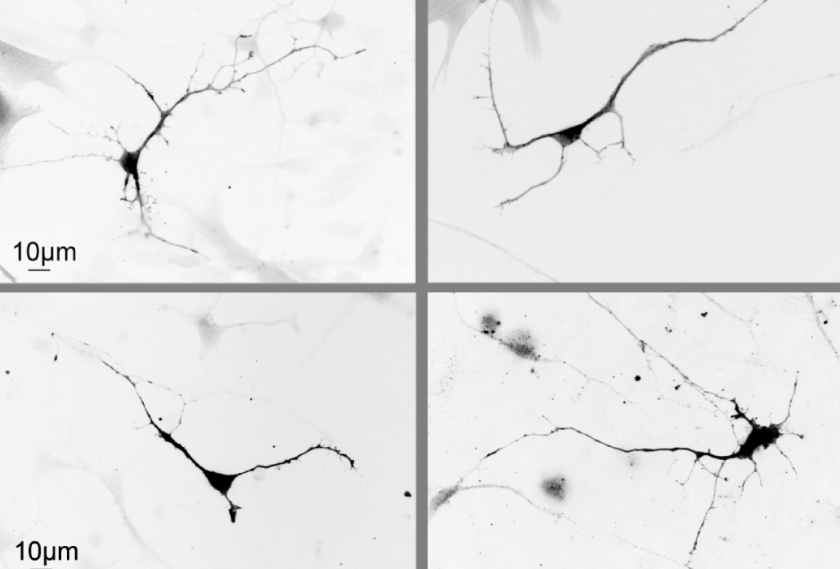

The researchers used human stem cells to generate neurons that express low levels of ASH1L protein. The ASH1L-deficient neurons had fewer and shorter projections and larger cell bodies than control neurons did.

The changes could affect the neurons’ ability to send signals across synapses, the junctions between neurons, says Janay Vacharasin, a doctoral student in Sofia Lizarraga’s lab at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, who presented the work.

“If you scale this up to the brain, maybe [the neurons] can’t connect to the right systems or different areas of the brain, since they can’t grow as well,” she says.

Next the researchers treated the neurons with an experimental drug that inhibits EZH2, an enzyme that represses gene transcription in a process regulated by ASH1L. After this treatment, the structure of the ASH1L neurons appeared more similar to that of control neurons.

In June, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved an inhibitor, called tazemetostat, similar to the one the team used to treat a form of lymphoma in adults.

Mouse brains:

The neuron findings echo those in ASH1L mice presented by Sally Camper’s lab at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

That team created mice missing one or both copies of ASH1L throughout their bodies. They also made mice missing the gene only in the cerebral cortex or neural progenitor cells, using a system that edits genes only when mice are given a drug called tamoxifen.

Most of the mice lacking ASH1L died within two weeks of birth, a finding in line with the observation that people with mutations in ASH1L typically have those changes in only one copy of the gene.

Mice missing both copies of the gene showed differences in brain development from the control mice, including unusually large ventricles — fluid-containing cavities deep within the brain. The team is currently probing whether other parts of the brain are affected.

“What we can tell is, there is definitely a structural abnormality of the brain,” says Kevin Toolan, a graduate student in Camper’s lab, who presented the work.

They also found that knocking out ASH1L changed the expression of other genes associated with autism, including NRXN2. But these results are preliminary, Toolan says.

Both studies found that ASH1L mutations seem to disrupt a signaling pathway necessary for neurons to grow, Vacharasin says. She plans to next study cells derived from autistic people with mutations in the gene.

Read more reports from the 2021 Society for Neuroscience Global Connectome.