Lingering gaps permeate public perception of science

When it comes to research, scientists and the public are often at odds. It’s a long-standing problem, but the results of a survey released last week reveal that in particular areas, this opinion gap has grown.

When it comes to research, scientists and the public don’t always see eye to eye. It’s a long-standing problem, but the results of survey released last week reveal where this opinion gap has grown.

Researchers from the Pew Research Center surveyed 3,748 members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and 2,002 men and women from the general public. They asked the participants questions probing their views on everything from the role of science in society to specific, touchy subjects.

The groups agree on the poor quality of school education in science, technology, engineering and math, with 46 percent of scientists and 29 percent of the public giving it a ranking of ‘below average.’

There is also overlap in views about childhood vaccines, with 86 percent of scientists and 68 percent of the public believing they should be required, despite claims falsely linking them to autism. These figures haven’t changed much since a 2009 Pew survey, but the fact that one-third of the public thinks vaccines should be optional is worrying, especially in light of the current measles outbreak spreading across the country.

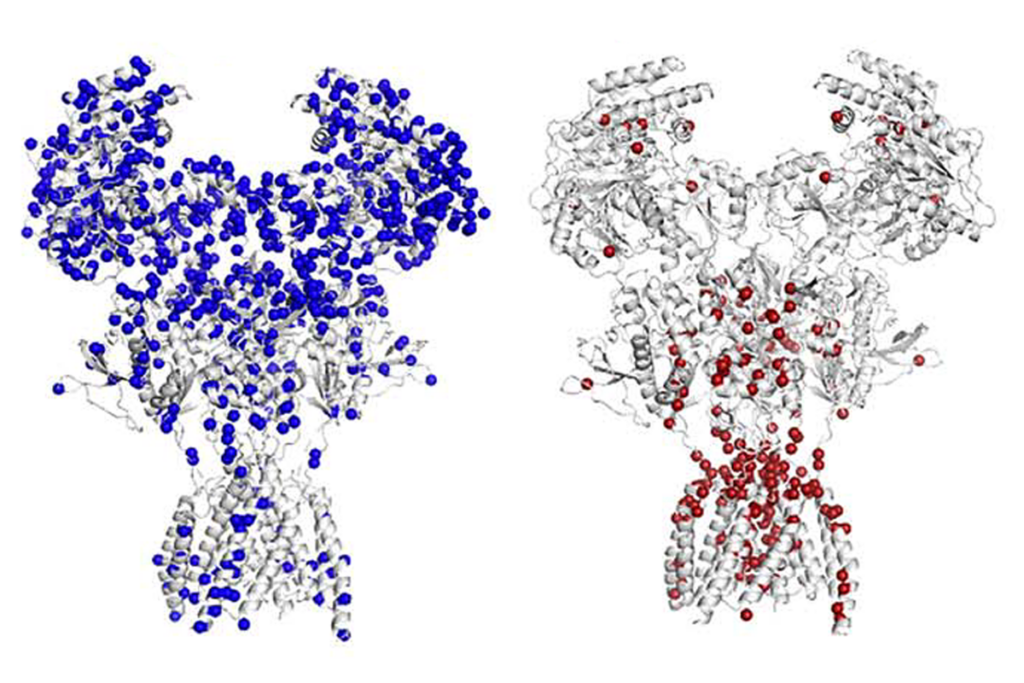

On most other hot-button issues, scientists and citizens are more divided. The biggest gap is for genetically modified (GM) foods, which are considered unsafe by 57 percent of the public but only 12 percent of scientists. There is also a considerable split on evolution, with 98 percent of scientists endorsing the view that humans evolved over time, compared with just 65 percent of the public.

The two groups also diverge on the state of science in the U.S. A whopping 92 percent of scientists say the country’s scientific achievements are “the best” or “among the best,” an upbeat assessment shared by only 54 percent of the public. The gulf on this issue has grown since 2009, when 65 percent of the public considered the U.S. a scientific leader.

“If we don’t have a receptive public that fully understands the nature of science, it makes it much more difficult for society to reap the benefits,” Alan Leshner, chief executive officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, said in a press briefing about the findings.

The scientists are not entirely enthusiastic about the state of science in the U.S., either: Only 52 percent say, “This is a good time for science,” down from 76 percent in 2009.

The split on genetically modified foods may reflect the public’s lack of understanding about the most fundamental aspects of the issue, including what makes something a GM food. The only way to fill the information void, Leshner says in an editorial accompanying the survey results, is for scientists to engage in “genuine, respectful dialogues” with the public.

It’s important not only to help people understand the science, he says, but to acknowledge their fears, political views and religious beliefs.

Research suggests Leshner is right: Simply giving people accurate information is often not enough to influence their opinions and actions; sometimes, these efforts can even backfire. A study last year in Pediatrics found, for example, that pointing out the lack of evidence for a link between vaccines and autism actually made skeptical parents less likely to vaccinate their children. If talking at people doesn’t work, perhaps listening to them will be more effective.

Recommended reading

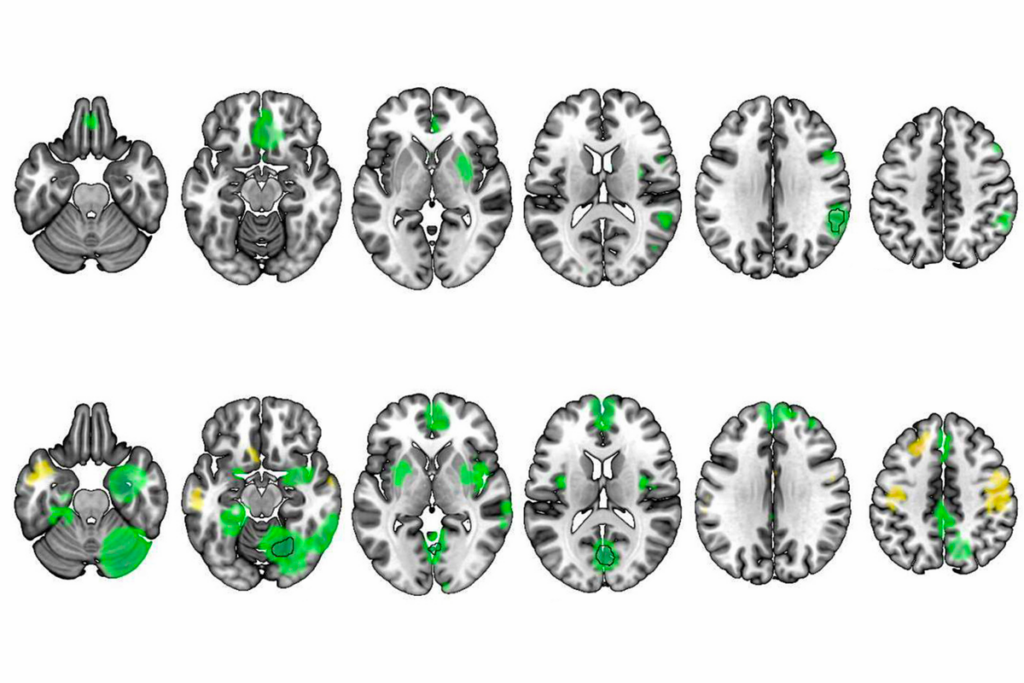

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Autism traits, mental health conditions interact in sex-dependent ways in early development

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Emotional dysregulation; NMDA receptor variation; frank autism

BCL11A-related intellectual developmental disorder; intervention dosage; gray-matter volume