Large survey of children hints at true autism prevalence in Vietnam

Less than 1 percent of young children in northern Vietnam have autism, but this prevalence is higher than in previous reports.

About 0.75 percent of young children in northern Vietnam have autism, according to a large study of children in the region1.

The study is part of a rare effort to systematically determine the prevalence of autism in the country and may represent the most accurate estimate yet.

Three other studies from 2012 to 2014, two of them unpublished, suggested a prevalence of 0.4 to 0.5 percent in northern Vietnam2. The new findings indicate that autism prevalence is increasing in the country, consistent with trends worldwide, says Thi Vui Le, vice head of demography and reproductive health at Hanoi University of Public Health.

The demand for autism services in the country is likewise growing: The number of autistic people admitted to the National Pediatrics Hospital in Hanoi increased threefold from 2000 to 2007 and fourfold from 2008 to 2010. Autism services in Vietnam are available mainly in major cities, Le says.

The new prevalence figure lines up with estimates from other low-resource countries. For example, autism occurs in about 1 percent of the population in India and China.

“It’s always nice to see data from underrepresented world regions, and the findings certainly contribute to filling important gaps in prevalence estimates,” says Mayada Elsabbagh, assistant professor of neurology and neurosurgery at McGill University in Montreal, who was not involved in the work.

Impressive scale:

Le and her team obtained lists of all children aged 18 to 30 months living in two provinces in northern Vietnam — Thai Binh and Hoa Binh — and the Vietnamese capital of Hanoi. They randomly selected about 2,000 names from nine lists — 17,754 children in total.

They then sent trained local healthcare workers to the children’s homes to administer a Vietnamese translation of the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), a widely used screening questionnaire. The workers also collected information about the age, education level, occupation and annual income of each child’s parents. About three-quarters of the children live in rural areas.

Of the 17,277 children whose parents completed the M-CHAT, 255 screened positive for autism. The researchers invited these children, and 340 others who screened negative, for a diagnostic assessment at local clinics. Pediatric neurologists at the clinics determined that 129 of the children who screened positive and one who screened negative have autism — a prevalence of 0.75 percent.

The doctors based their diagnoses on criteria in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. They used these criteria rather than the newest criteria in the fifth edition so that the results could be compared with those from previous studies, Le says. The work appeared in April in the International Journal of Mental Health Systems.

The study’s scale is impressive, says Bhismadev Chakrabarti, professor of neuroscience at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the work. “It’s a very good and systematic effort in doing a population-based study in a setting where both awareness and research capacity is not very high,” he says.

Puzzling picture:

Autism is about four times as common in boys as in girls in Vietnam, consistent with patterns elsewhere. And it is nearly three times as prevalent in urban areas as in rural ones. This difference may be due to environmental factors, the researchers suggest, although the study was not designed to ferret out the reasons.

The prevalence of autism is close to five times higher among children of women who work as farmers (about 25 percent of mothers in the study) than among children of women employed by the government (16 percent of mothers).

This result is particularly puzzling, Chakrabarti says, as children of farming mothers tend to live in rural areas where prevalence is low, whereas children of government staff tend to live in urban centers.

“That is an unresolved issue and it’s definitely worth probing further,” he says.

Le’s team is conducting a similar survey involving four provinces in the central and southern regions of the country. The researchers plan to screen 42,000 children in all.

References:

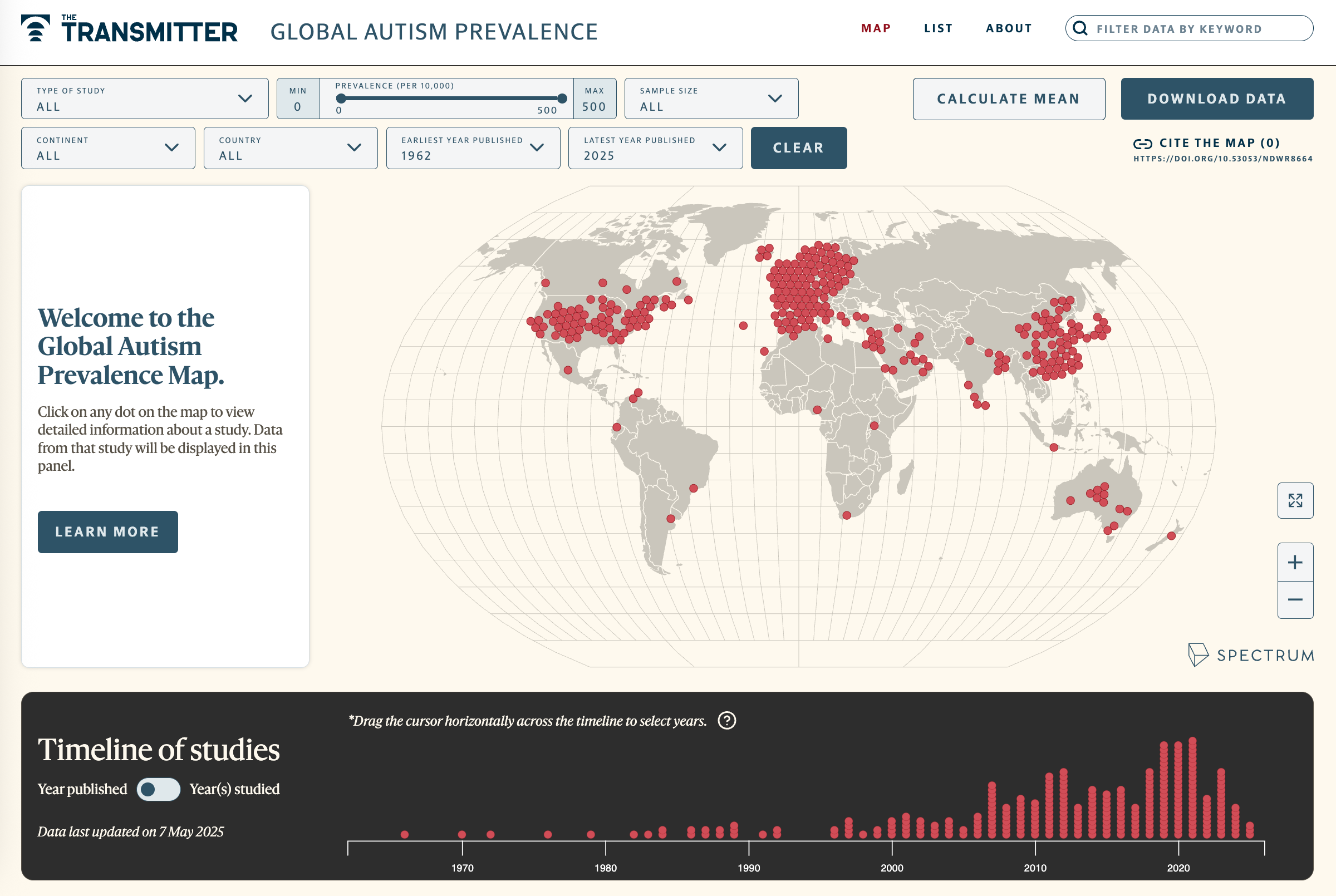

Visit our Global Autism Prevalence Map

Explore more >

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Autism prevalence increasing in children, adults, according to electronic medical records

Anti-seizure medications in pregnancy; TBR1 gene; microglia