Large study links autism to autoimmune disease in mothers

About one in ten women who have a child with autism have immune molecules in their bloodstream that react with proteins in the brain, according to a study published 20 August in Molecular Psychiatry.

About one in ten women who have a child with autism have immune molecules in their bloodstream that react with proteins in the brain, according to a study published 20 August in Molecular Psychiatry1.

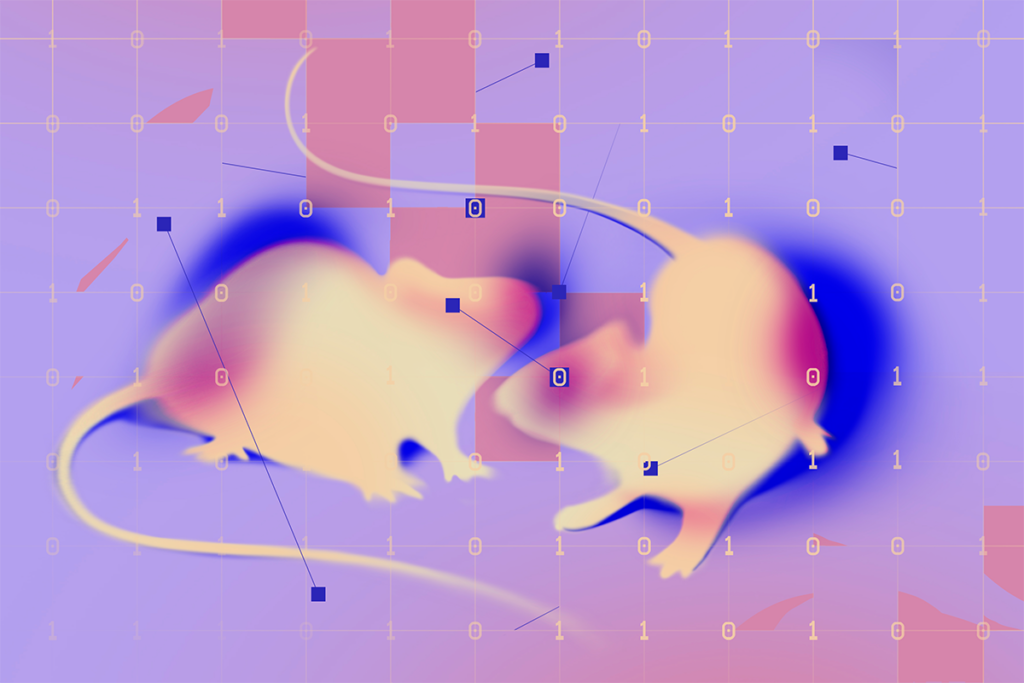

Several research groups have found these immune molecules, called antibodies, in mothers of children with autism, and have shown that prenatal exposure to the antibodies alters social behavior in mice and monkeys.

The new study, which includes more than 2,700 mothers of children with autism, is the largest survey yet on the prevalence of these anti-brain antibodies.

“It’s a very large sample size,” says study leader Betty Diamond, head of the Center for Autoimmune and Musculoskeletal Disorders at The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Long Island, New York. The scale gives a clearer impression of the prevalence of these antibodies, she says.

Antibodies help the body’s immune system recognize and fight off disease-causing microorganisms such as bacteria and viruses, but sometimes the body mistakenly produces antibodies to its own proteins. In some people, this results in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, in which the body attacks its own tissues.

Researchers say anti-brain antibodies do not harm the brains of the women who produce them because of the blood-brain barrier, a filter that prevents most molecules from entering the brain. But the immature blood-brain barrier of a developing fetus may let them through, allowing them to damage the brain and perhaps cause autism.

Diamond’s team also found that women who have autism-linked antibodies are more likely to have other markers of autoimmunity compared with those who don’t carry these antibodies. Studies have shown that women with an autoimmune disease also have an increased risk of having a child with autism2.

“This ties together the epidemiological finding that women who have autoimmune disease are more likely to have kids with autism, with the idea that there are actually antibodies against fetal brain in their serum,” says Paul Patterson, professor of biology at the California Institute of Technology, who was not involved in the work.

Sample size:

In the new study, Diamond’s team screened blood plasma samples from 2,431 mothers enrolled in the Simons Simplex Collection (SSC). The SSC is a registry of families with one child affected by autism and unaffected parents and siblings, and is funded by SFARI.org’s parent organization.

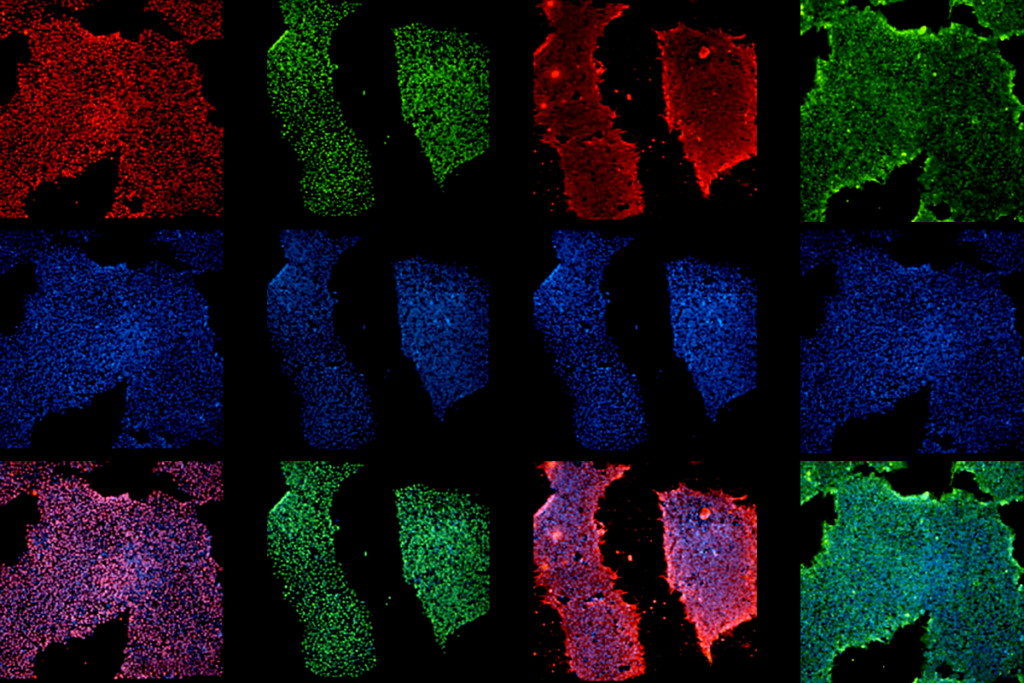

The researchers found that plasma from 260 of the women, or 10.5 percent, reacts strongly with mouse brain tissue, a signal that the blood contains anti-brain antibodies.

They also screened samples from 318 mothers enrolled in a different autism registry, the Autism Genetic Resource Exchange, and found that 28, or 8.8 percent, of them also have anti-brain antibodies.

In contrast, among a group of 653 controls drawn from the general population of women of childbearing age in New York City, only 17, or 2.6 percent, carry the autism-linked antibodies.

This means that the prevalence of anti-brain antibodies is about four times greater among mothers of children with autism than among the controls.

However, “The control population could have had mothers of children with autism in it,” notes Judy Van de Water, professor of clinical immunology at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the work. In fact, some of the women in the control group may not have children at all.

Still, Van de Water says, the study “corroborates, from an independent investigator, that women in this population have a higher incidence” of the antibodies.

Van de Water has found anti-brain antibodies in autism mothers who are part of the Childhood Autism Risk from Genetics and the Environment study using a different methodology3, known as Western blotting, and says that the differences in study design make the similar results more persuasive. “It’s further support for this potential pathway to autism,” she says.

However, she cautions that measuring reactivity to mouse brain tissue also has drawbacks, because of the action of chemicals used in preparing the brain tissue for analysis. “The perfusion and fixation process that you have to go through is going to alter some of the antigens,” the proteins to which the antibodies bind, she says. This may ‘mask’ some of the binding patterns that occur in live brains.

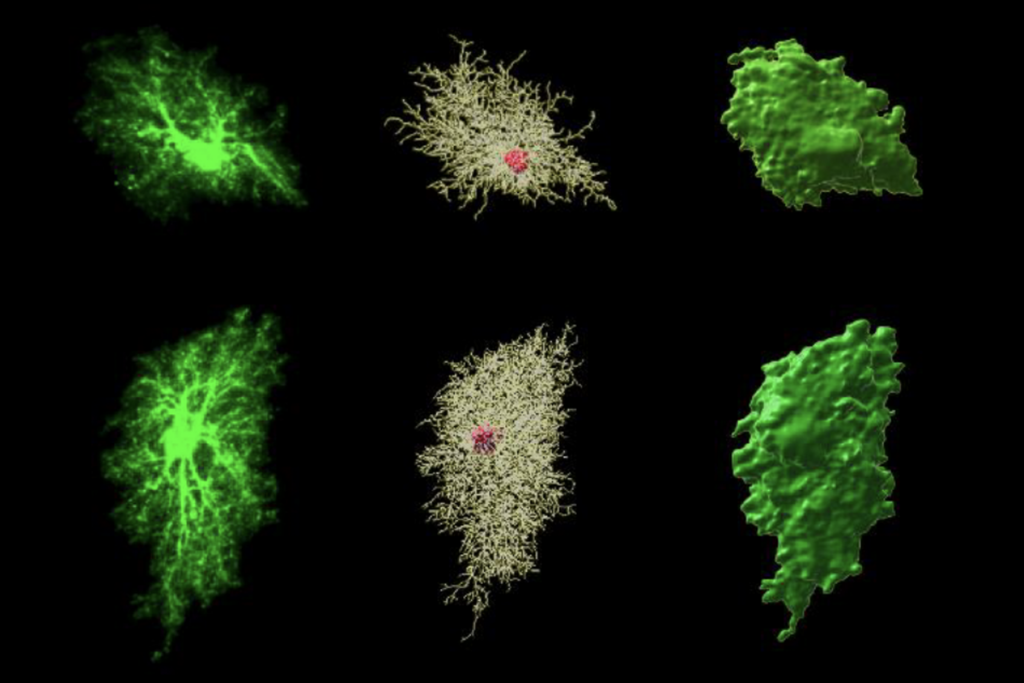

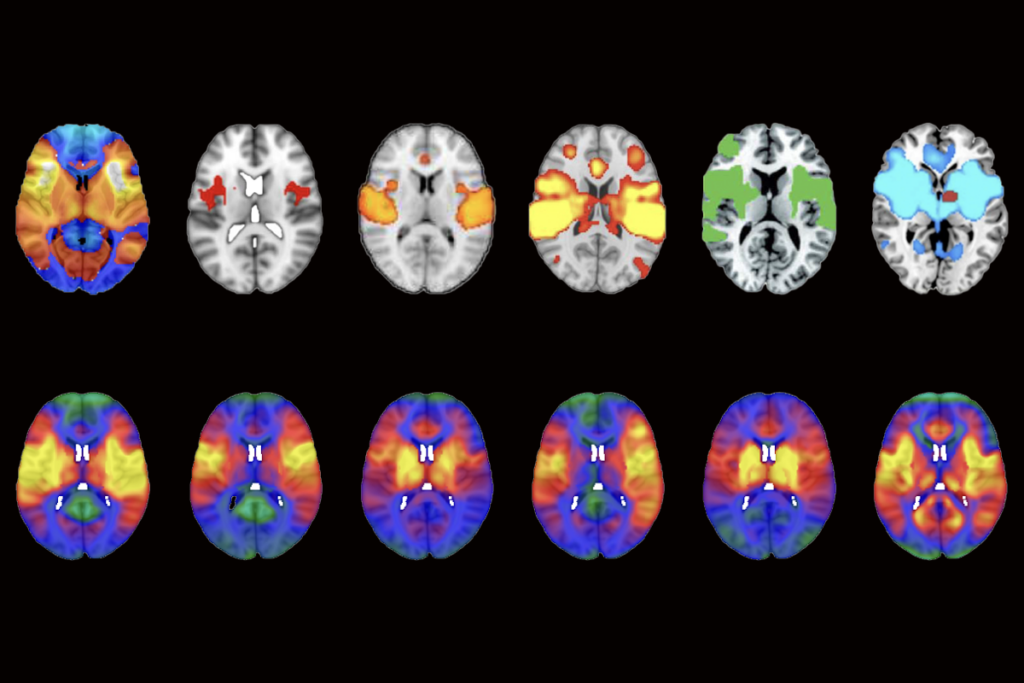

Using the mouse brain enabled Diamond’s team to pinpoint which regions of the brain the antibodies affect. They found that the antibodies bind primarily to neurons in the frontal cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum, all areas that have been implicated in autism.

Fetal findings:

Patterson notes that the researchers tested binding of the antibodies to adult mouse brain, but protein expression in the adult brain is often very different from that in the fetal brain. “Optimally, one would like to know what the binding is to fetal human brain or fetal monkey brain,” he says.

According to Diamond, the team did find that the antibodies also bind to fetal human brain extracts and to whole fetal mouse brain. However, she says, it wasn’t possible to see which regions of fetal mouse brain they bind to because the brains are too small.

Her team performed several other analyses that uncovered tantalizing links between autism-linked antibodies and autoimmunity more generally.

First, they screened the blood of study participants for anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs), which bind to molecules found in the cell nucleus and are commonly found in people with a variety of different autoimmune disorders. They found that 52 percent of autism mothers who carry anti-brain antibodies also have ANAs. In contrast, only 13.4 percent of autism mothers without anti-brain antibodies have ANAs, as do 15 percent of controls.

Mothers with anti-brain antibodies are also more likely to have autoimmune diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, compared with mothers who don’t have these antibodies.

Finally, the team screened a group of 363 women with rheumatoid arthritis for autism-linked antibodies. They found that 13.5 percent of these women have anti-brain antibodies, similar to the prevalence among mothers of children with autism and much higher than that of controls.

That’s a rather puzzling finding, Patterson says. “If they’re just as likely to be found in rheumatoid arthritis women, that means they’re not especially specific to autism,” he says.

But a link between rheumatoid arthritis and autism isn’t unheard of, Diamond says. In a separate series of experiments, she has found that antibodies that cause kidney damage in women with lupus also cause cognitive impairment in mice exposed to the antibodies in utero4.

Diamond says she has unpublished data indicating that some of the brain proteins that bind the antibodies are already implicated in autism or other neurodevelopmental disorders — but declined to reveal details. Are any of the targets she has identified the same as those reported by Van de Water and her colleagues in July? “It’s sort of interesting,” Diamond says. “They’re not.”

References:

1: Brimberg L. et al. Mol. Psychiatry Epub ahead of print (2013) PubMed

2: Atladóttir H.O. et al. Pediatrics 124, 687-694 (2009) PubMed

3: Braunschweig D. et al. Transl. Psychiatry 3, e277 (2013) PubMed

4: Lee J.Y. et al. Nat. Med. 15, 91-96 (2009) PubMed

Recommended reading

Common and rare variants shape distinct genetic architecture of autism in African Americans

Profiles of neurodevelopmental conditions; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

How artificial agents can help us understand social recognition

Methodological flaw may upend network mapping tool